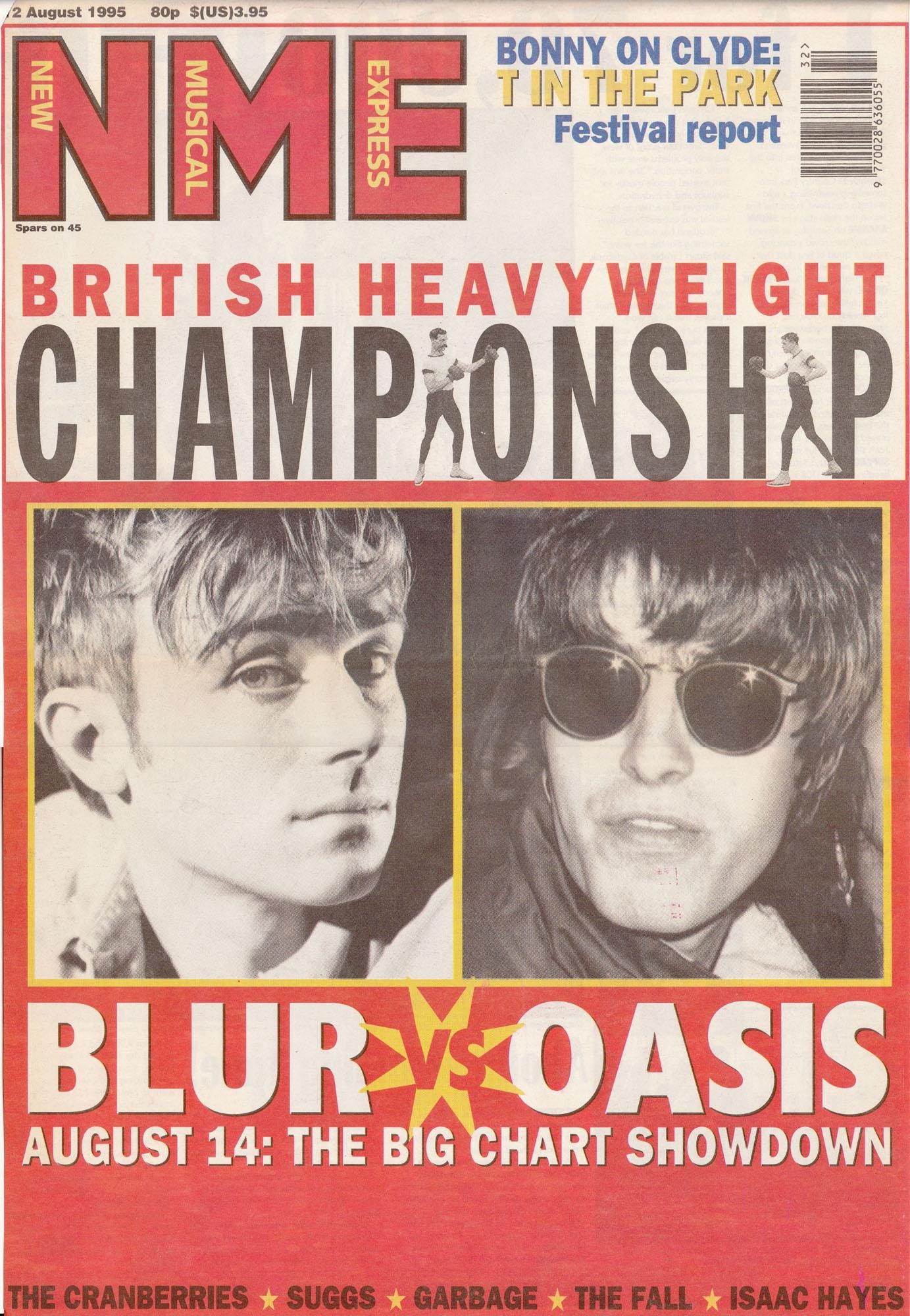

From where I sit, an Oasis reunion is just another 90s band hitting the road for cash. But clearly there’s a lot more to this story for many in the UK. Within days of the announcement, the Guardian had run one column declaring that “Oasis are the most damaging pop-cultural force in recent British history,” and another testifying that “The real magic of Oasis… [is] they made a better kind of Britain seem briefly possible.” In yet another Guardian piece the brilliant Stewart Lee split the difference, or rather managed to make both ideas the same by taking the piss out of the band and himself for enjoying them. “Oasis are a guilty pleasure for a pseudo-intellectual like me,” he wrote.

Britpop is still, it seems, a battle. But is it a genre? Oasis sound like “classic rock” to me, meaning, anything that fits a radio station that plays, “Best of the 60s, 70s, 80s… and 90s!” with the final decade added in an excited rising tone, as if it were daringly contemporary. Stewart Lee again deserves the last word on this issue: “Oasis represented a massive, if mighty, full stop.” Rock as retread. It was reunion material from the get-go.

Yet genre terms that draw on national image spark particular kinds of opinion columns. Here across the water, the term Americana gives me the racist willies. Are we really going to say there’s some music that’s more American than James Brown? Than Louis Armstrong? Well, then… what are we saying when we use that term?

Germans know from corrosive nationalism, and in the excellent new oral history of Krautrock, Neu Klang by Christopher Dallach, it’s almost exclusively the foreigners quoted who try and discuss any particular “Germanness” to this music. Brian Eno ventures that “There is a characteristic which runs through much German music: it’s economical, spare, austere, focused.” (Never mind Wagner, I suppose?) But Eno’s musical collaborator Hans-Joachim Roedelius, of Cluster and Harmonia, clearly knows that way madness lies. “Our sound wasn’t German,” he says, which is one way to deal with it. Holger Czukay of Can similarly distances himself from any potential definition: “I never thought it referred to me anyway.” Jean-Hervé Peron of Faust dismisses the term by delving even further into such distinctions: “I was French, Zappi was Austrian, Rudolf was half Russian, plus a Swabian and a Friesian. And people say we’re a model German band. Absurd.”

My drumming hero Jaki Liebezeit of Can has I think the best take of all: “I don’t mind ‘Kraut,’” he says. “‘Rock’ is much worse! Rock doesn’t stand for anything at all. You get Nazis doing rock.”

What are you going to do with that one, Britpop and Americana? When I was a teen I worked a summer job as a boys camp counselor, and one of my colleagues there was from a wealthy Italian family who had sent him to improve his English. He told me once why he admired Bruce Springsteen. “American rock is so pure. So strong!” he said, jutting his jaw and shaking his fist like a Mussolini in shorts and a camp logo T. I was as obsessed at the time with Born to Run as any of my classmates back home. But it never quite sounded the same to me again. (I was relieved when Darkness on the Edge of Town came out and tempered the bombast a bit.)

As avoidant as the musicians of Krautrock are of Teutonic stereotypes, none of them shy away from discussing specifics of the social and political milieu they came from. In Neu Klang, this “generation of 68ers” collectively trace their upbringing in homes scarred by the Nazi years, early education in a still conservative but conflicted postwar West Germany, and liberation of various sorts through the cultural upheavals of the 1960s. Class backgrounds are a frequent reference point in this oral history. Kraftwerk are not just bourgeois but referred to as “upper class” – hence all those expensive machines they used! (Not to mention the costumes: “Kraftwerk would stroll around the center of Düsseldorf every day in their black leather outfits, including black gloves. They were always dressed to the nines.”) Florian Fricke of Popul Vuh also acquired an early, very expensive Moog through family wealth - in his case it was a wedding gift from his wife. Bandmate Frank Fiedler describes Fricke’s personal studio at the time:

“He had his Moog 3 in the house at Stadlberg, outside Miesbach where the mountains start. The rooms were huge, the Moog was set up in this enormous attic room. It was a 400-year-old farmhouse at the top of a hill, with a view of the Alps and the highlands. You could look down at the valleys as you played the Moog, with the Alps looming behind them, which was obviously very inspiring.”

Others came from more modest backgrounds, middle class or working class families broken by the war and struggling in the 1950s. Still, these musicians’ interactions with the West German monied classes are peppered throughout the stories of these bands. Renate Knaup of Amon Düül lived in the notorious leftist Kommune 1 in West Berlin, where,

“I was still having to work, but all the men in the commune had rich parents… Only Auntie Renate had to toil and slog… I worked until five o’clock and by the time I got back to the commune, the others had already done all sorts of things together. There were days when they wanted to use that against me, but I didn’t let them get to me. And then music gradually took over. Once we started playing more and more paid gigs, I handed in my notice at work. But it was unthinkable for the financially independent men to pass the hat round for Renate now and then. Their solidarity didn’t extend to money.”

Holger Czukay claims he decided after university that the best path to a career in music would be marrying rich, so he took a job teaching at a fancy boarding school in Switzerland to meet a wealthy wife – but ended up finding Can’s future guitarist Michael Karoli there instead.

Perhaps most unexpectedly, Faust – that supremely strange and scattered band with borderline unintelligible albums – have one of those mad rock biographies where a well-connected manager (Uwe Nettelbeck) with (again!) a wealthy wife (Petra Krause) talks record labels into funding wildly overindulgent lifestyles. Hans-Joachim Irmler describes how they recorded their debut album:

“First we moved into Petra Nettelbeck’s father’s hunting lodge on the heath; he’d made a fortune in shipping. We stayed there until they found us a suitable studio. It turned out to be a former village school in this hamlet called Wümme, near Hamburg. We did have a good budget, though. For one thing, they put in such effective heating that you had to walk around naked… Of course, we liked walking around naked.”

Jean-Hervé Peron picks up the story:

“We had a very nice life there, with the Polydor record company paying for everything. Apparently, we still owe them 50,000 euros, or so they say. At the time it was several hundred thousand… We’d even installed microphones in bed so we could record everything. Sometimes I’d lie there and yell: ‘Kurt! Press “record”!’ Kurt Graupner was our recording engineer, booked by Polydor.”

After getting Polydor to hire the grandest music hall in Hamburg for their first-ever live show, billed as quadraphonic but without any tech check or even musical rehearsal beforehand (“All the audience saw in the end was a band on stage who had no idea how to play live,” says Jean-Hervé Peron), the record label had enough. Incredibly, Uwe Nettelbeck then found Richard Branson to fund the entire adventure again - only in England. “Branson had a studio near Oxford, actually more of a castle, and that’s where we recorded,” says Zappi Diermaier. “Mike Oldfield… made Tubular Bells there all on his own. It wasn’t our bag, though – way too clean.” As Simon Draper of Virgin Records tells it,

“We put them in the Manor Studio to record their new album… Then they wrote me a list of everything they thought was ‘Scheisse’. They didn’t even like the flat we’d put them in in London. I was twenty-two at the time, doing my best. I’d have given my right arm to live in a flat like that, but it wasn’t good enough for Faust.”

Zappi Diermaier explains: “After a while we’d had enough of staying at the Manor. We didn’t like the food there any more. So we left and moved into a five-star hotel. We got them to send the bill to Richard Branson…”

Who knew? I had a very different image of Faust from listening to the albums. Not that I had conjured up some idea of a quintessentially “German” band – just a bunch of hippies, really. Is that a genre? If it is, it wouldn’t be “Krautrock.” But as this endlessly entertaining oral history makes clear, that tag would hardly fit any of these bands much better – even though they were all deeply embedded in West German society and politics of the 1960s and 70s. Just as Oasis and Blur were in the “cool Britannia” of the 1990s.

Ultimately, genres based around national identity like Krautrock, Britpop and Americana make for poorly constructed musical groupings. Yes a song can make emotions surge, including political and therefore also nationalist ones (the Kamala Harris campaign’s use of Beyoncé’s “Freedom” is a powerful, and for me positive, example at the moment). But what the musicians in Neu Klang detail, through their willingness to discuss identity along lines other than nationalism, are the more meaningful ways music is enmeshed in political and economic culture. Perhaps Krautrock is a particularly good case study for this, given the generation of 68ers allergy to ideologies in general, and ones touching on definitions of what a nation is, or who belongs in it, in particular.

Also: does anyone really want a national identity built around guys sending five-star hotel bills to their record label?

Listening to: Troubadour, by Dorothy Carter

Cooking: corn, tomatoes and okra

Great post.

Re: the Krautrock term. My parents, who are of the Krautrock/68ers generation, always despised it. Apparently it was coined by English writers. I've always wondered what it's supposed to mean, and I absolutely agree with Liebezeit. There's not much 'rock' in Kraftwerk, Tangerine Dream, Cluster or Harmonia. Can and Neu! might be a bit closer to rock regarding style and personnel; they might be the earliest precursors of what we'd call 'post-rock' in the 1990s. (I'm still referring to Talk Talk, Slint and Tortoise; absolutely aware that the next generation used that term for semi-awful 2000s crescendocore.)

I really need to dig into Neu Klang, but the stuff about Oasis representing the dawn of "the retread" era of rock feels on the money—as does your thought on the term "Americana," which gives me a similar sense of discomfort. Great read, Damon, thanks for sharing it.