Thurston [to fan]: People see rock and roll as youth culture and when youth culture becomes monopolized by big business, what are the youth to do? Do you have any idea? I think we should destroy the bogus capitalist process that is destroying youth culture by mass marketing and commercial paranoia behavior control - and the first step is to destroy the record companies. Do you not agree?

Thurston [on stage]: This is called -

Kim: Hey, did you know that Punk Rock finally broke in '91?

Thurston: - It's called Teen Age Riot.

Back in 1991, I thought I’d already seen the worst of the music industry. Big businesses – major record labels, glossy magazines and MTV - had swooped down on the misfit scene we were a part of and eagerly taken up the profitable hypocrisy of selling our disgust at the act of selling. It’s the contradiction you see Sonic Youth trying to negotiate in their tour film with Nirvana, The Year Punk Broke.

I couldn’t watch the film at the time. Our entry in the alt rock sweepstakes, Galaxie 500, had recently broken up from similar pressures and it all felt too emotional, too overwhelming. I knew many of the participants, knew what they were going through, knew that some would manage (nothing but respect for Sonic Youth) and some would not.

I finally watched the film this week, 30 years late. Or maybe right on time?

We are in a far worse situation than we were in 1991. Thurston’s part-jokey, part-deadly serious condemnation of the industry then - “When youth culture becomes monopolized by big business, what are the youth to do?” – feels like an understatement today. It’s no longer just about youth culture; it’s all cultural production that’s monopolized by big business. Thirty years of capital consolidation have created monopolies larger and more disconnected from “content” than we could have imagined even at our snottiest in the 90s. The major labels, music mags, and MTV still needed musicians, after all.

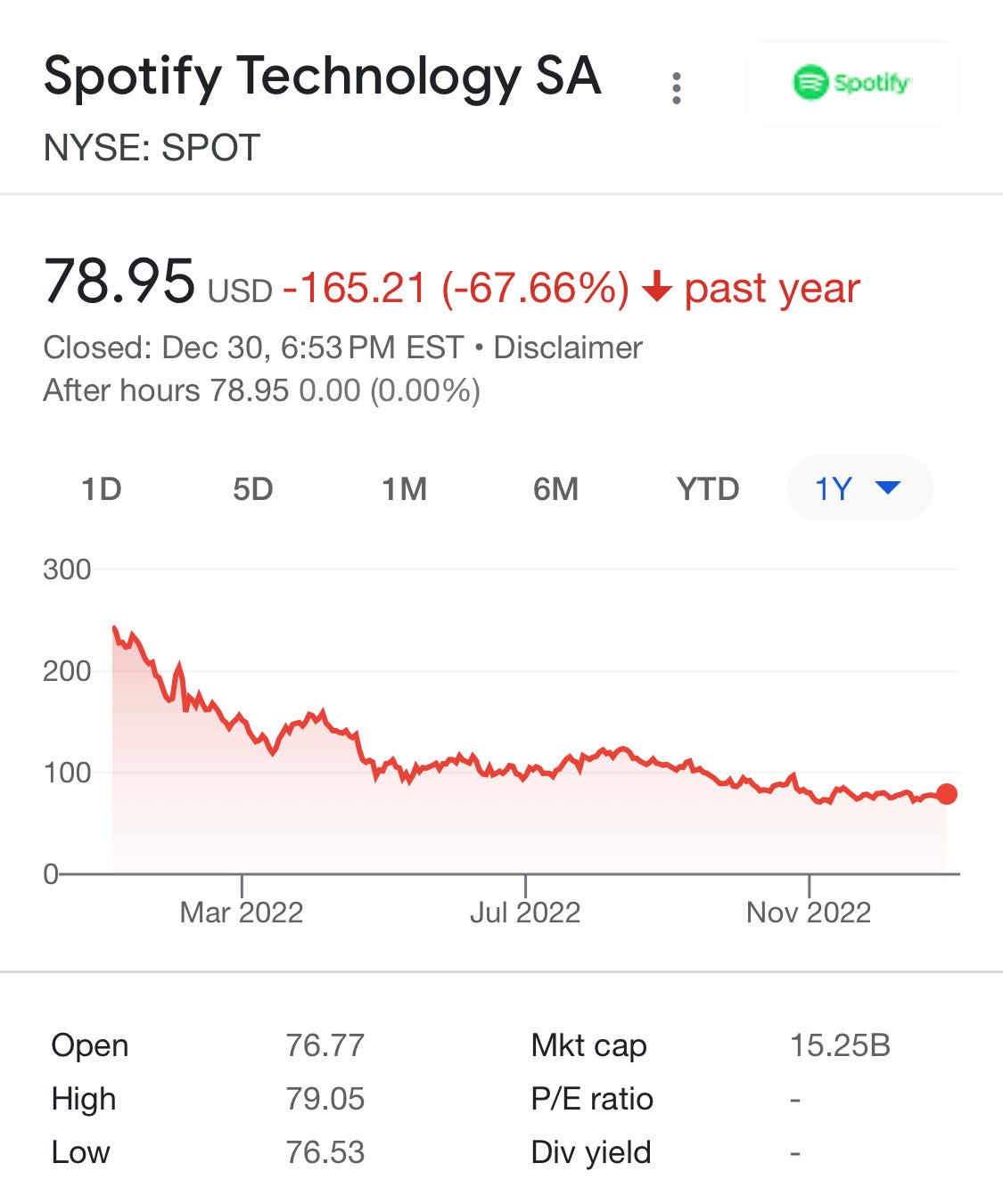

But Apple doesn’t – music is the least of their business. Same goes for Amazon. And what Spotify seems to need is to get away from music as fast as it can. With so much attention paid to Tesla’s precipitous fall in value, many seem to have overlooked that Spotify also lost nearly 70% of its market capital this year.

If you read investor’s bulletins about the company, they take for granted that Spotify will never turn a profit from music. The question they ask is, can the company redirect the money it draws out of music into a more profitable pursuit.

Where does that leave us musicians, both youthful and no longer youthful? Our livelihood has been monopolized not only by big business, but big business whose success depends on having nothing to do with music.

The strain is real. Two weeks ago in Pitchfork, Jenn Pelly published a remarkable survey of the psychic toll this is taking on musicians: “Confronting Music’s Mental Health Crisis.”

“In 2022, there are so many systemic issues at the root of the mental health crisis in music that the conversation begins to feel perilously unwieldy. Streaming has decimated the economy of music, creating financial stress for artists as they’re instructed to relentlessly tour. Corporate consolidation has exacerbated those problems. Self-employed workers face barriers to health insurance across the board in the U.S., with its broken healthcare system. Musicians and therapists alike cite social media as an extenuating factor, eroding boundaries and contorting our senses of self. There are also fraudulent cultural myths about tortured artists, and a need for stronger labor consciousness among working musicians. Meanwhile, the anxiety of pandemic health risks persists.”

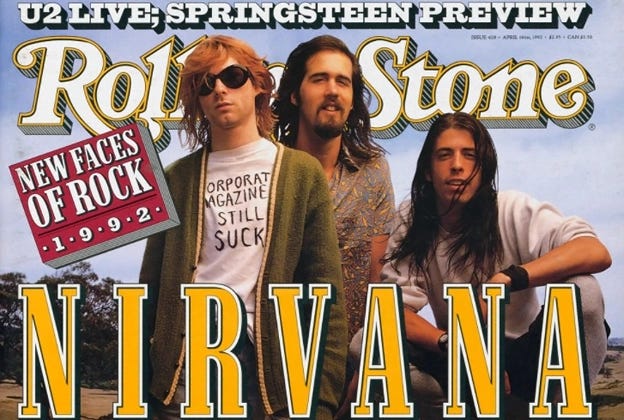

I have never seen the issue of mental health for musicians addressed so directly - and in a Condé Nast publication no less. Not that we were unaware of this kind of stress thirty years ago. But discussing it head on is very different than Thurston playing the wise fool in The Year Punk Broke. Or Kurt Cobain highlighting the paradoxes of his career via t-shirt on the cover of Rolling Stone.

That Rolling Stone cover story, by Michael Azerrad, makes a chilling contrast with Jenn Pelly’s piece. The extreme mental strain is there, along with addiction – it is described in no uncertain terms. But it’s always followed by a quick turn toward the sexy image of a self-destructive rock star.

“Having eaten virtually nothing for over more than two weeks, Cobain is strikingly gaunt and frail, far from the stubbly doughboy who smirked out from a photo inside Nevermind. It’s hard to believe this is the same guy who smashes guitars and wails with such violence – until you notice his blazing blue eyes and the faded pink and purple streaks in his hair.”

Selling mental illness as attractive has always been a problem. But as Jenn Pelly’s article makes clear, it’s far from the only problem at present. When Sonic Youth and Nirvana toured Europe in 1991, they weren’t also facing material shortfalls. By contrast, “Why Many Musicians Can No Longer Afford to Tour” is the Guardian’s headline for a summation of the live music scene in 2022. Even “successful” acts – the Sonic Youths and Nirvanas of today - are facing an economically unsustainable situation.

All of music, in other words, is currently on the same trajectory as Spotify stock. Not by coincidence. But Spotify’s probable solution – get out of the music business – isn’t an option for artists. This isn’t just a business to us. That’s what Thurston is saying, in his inimitable way, in The Year Punk Broke.

Not that I have no hope for 2023. Hitting bottom can be part of recovery. Been down so long it looks like up to me.

Listening to: Laraaji, Segue to Infinity

Cooking: O-zoni

Ok, I see what you are saying. The centralized, monopolistic corporate impulse is going to kill off all kinds of industries. However, this not the end. I don’t know all the steps in between, but this is leading to a decentralized world of local communities. This world does not resemble a corporate structure with all its administrative overhead. It is rather a network that shares. I realize that what I am saying is not new. The ideas have been out there. The application, the action to implement, has not been there. Why? Because we have been programmed to see the world as having a controlling center with the real enterprises out on the periphery. When the center greedily abandons the periphery, new centers form around the peripheral enterprises. This not just happening to the music industry. It is happening to every place where creativity has a real world connection to people. For the past year on Substack, I’ve been writing. My subscription numbers grew when I started dialoguing with other writers in the comments of their posts. What I am saying is that we have to stop marketing and start interacting with each other. New communities will emerge from that process. I don’t know if this solves the immediate problem that you describe. But it is all that we will have when the system collapses. There is no single, simple answer. There is only shared hardship out of which a new future can be created. And the beauty of this is that it will spark fresh creative output. I am already seeing this happen.

There should be an independent network of record labels, venues, online 'zines, and college radio serving a kind of music that could be "marketed" as "indie rock.".... Uh, oh, wait a minute. Sorry.