This week Twitter was supposed to remove checks on verified accounts and do whatever else its autocratic owner decides to do next. It didn’t happen. And yet the destabilizing effect is just as real. No one knows when the next update will come, or what it will bring exactly – which means users not only have no say in the matter, but can’t even adjust in anticipation. It’s been destructive to the use of the platform as a communicative tool, to say the least.

And yet, this erratic behavior is all too familiar from our use of other, supposedly more rationally managed software that we depend on. Who knows what the next operating system update will do to the digital tools we use each day. Which older files will be rendered unreadable. What painstakingly curated digital music collection will suddenly be scrambled.

Which is why, two years ago this month, I disconnected my recording studio from the internet entirely. This wasn’t an analog rebellion – I didn’t trash my studio computer and replace it with vintage tape machines. On the contrary, I did it to preserve the digital audio tools I have come to rely on. I wanted my tools to continue working the way I know. That familiarity is part of my skillset in the studio - and as a self-taught, DIY audio engineer, I don’t have a lot of skills to spare.

What had happened earlier that spring was a routine software update to a piece of my digital studio. But the update rendered a different, crucial piece incompatible. So I updated that. Which made another piece incompatible – an expensive piece. And I couldn’t update that. (This was at the height of the pandemic. Who could afford to update anything?)

Moreover, I was in the middle of a project – mixing our album A Sky Record – and I very much wanted to continue along the lines I had started. In the digital era, we are all accustomed to fast moving technology – but could I really no longer make it through even one album from start to finish on the same equipment? And if not, how do we ever come to any kind of mastery of our tools?

The network betraying my studio was also the source of answers to such questions, of course; I went online and started asking everyone I know in audio engineering how to deal with this situation. To my surprise, the advice I got back was nearly unanimous: unplug. Stop updating. Revert to the stable system you had before. And take everything offline so this doesn’t happen again.

It seemed a clever solution to my small-scale, personal studio problem. But I was taken aback when some of the professionals who offered this advice said it is what they do, too. Even with their very extensive skillsets. Could it be that some of the most sophisticated audio technicians I know - mastering engineers in particular, those tasked in our industry with maintaining and constantly improving audio standards - choose to ignore innovation for the sake of stability?

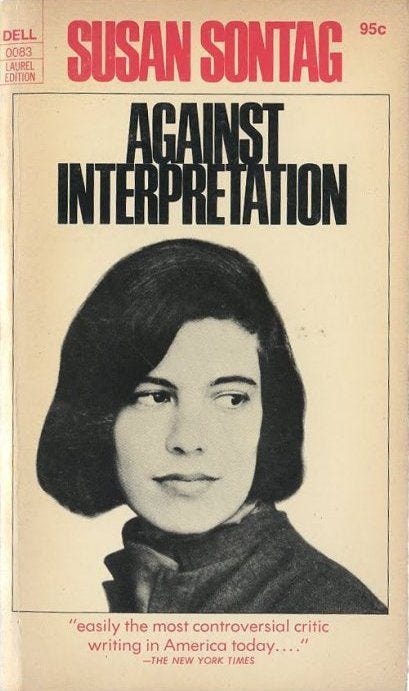

This counterintuitive approach reminded me of Susan Sontag’s early essay, “Against Interpretation” (1964), where she urged not only critics but artists themselves to ignore the contemporary rage for symbolism, for heavy interpretive frameworks. “What is important now is to recover our senses. We must learn to see more, to hear more, to feel more,” she wrote, trying to free Kafka and Beckett from the endless updates critics were then imposing on these texts. Sontag looked at mushrooming interpretations as so much distraction:

“Our task is not to find the maximum amount of content in a work of art, much less to squeeze more content out of the work than is already there. Our task is to cut back content so that we can see the thing at all.”

I took the advice. Updating my digital audio tools would give me more choices, more dropdown menus, more emulation of spaces I do not occupy, classic equipment I do not own, and a seemingly limitless ability to manipulate any sound that I can actually make with my body and my instruments. But were these the choices I needed? Or did I need to better see the thing I was making at all.

By that point, I had gone so far down the road of updates that I had to buy a pirate copy of an unsupported operating system to fully revert. I did. It worked. I finished the album. And my studio is still offline.

Of course, refusing to update - taking a stand against innovation - means staying put, at least technologically. Does that mean stylistically, too? It could – I cannot, without updating, take advantage of the latest digital audio products and therefore some of the latest trends.

But there’s another path to development, one that feels more productive to me personally in the digital environment, and it starts with making committed choices about tools and platforms. This is what I think the current owner of Twitter – who mistakes memes for wit – can’t appreciate. Limiting options can sometimes lead to wild creativity, the kind we witness in Kafka and Beckett in fact.

Recently, I had to dismantle my studio for an entirely different, very analog reason: plumbing repairs to the building we live in. And when I put it all back together, it worked the same as before, thank god. Isn’t that precisely what you hope for, in such a situation? Why can’t that be what we sometimes aim for in the digital environment, too.

Listening to: Maria del Mar Bonet, Miró

Cooking: Jerusalem artichokes - a gift from a friend’s early spring garden – simmered in milk and puréed

Looks like the timing of this post was better than I knew - today, Musk started choking access to Substack from Twitter… currently it seems any tweets with Substack links cannot be replied to (even by the author, no way to make a thread), or even simply liked. More innovative energy from a “disruptor.”

I’m a software engineer for a big tech company. We routinely lock down our tool chains for the same reasons; we need to have reproducible builds and remove variance.