A sound engineer observed to me recently that many young singers are not projecting into microphones, even in large venues, presumably because they came of age singing alone for Instagram or TikTok – no back wall to reach in a room, no audience chatter to overcome, no band volume to compete with, no need to rise above anything beyond their own accompanying instrument (if that). They might be in an arena filled with fans, but they are still addressing the mic as if it’s an iPhone.

Which is not to say you can’t be a great singer to an iPhone, or to a mic treated like an iPhone – “crooner” wasn’t always a positive term when it was introduced to describe intimate address through audio technology, either, though it applied to some of the best singers of the 20th century. But what the sound engineer’s observation made me think is the way a social situation is projected from the stage. We hear a singer address us as if we are observing them alone in their room making a video – and to some degree we then place them in that room, alone, with us observing. Or millions of us observing. It is the sound of virality, perhaps.

What might be truly different about this IG moment in music, to me, isn’t that technology is dictating changes – that’s always been the case – but that live music can project a social situation which isn’t exactly social. Virality is collective, yes, in the way a meme requires shared use to have meaning. But virality is nonetheless largely experienced alone. Some live shows I’ve been to lately have had nearly silent audiences, not just for the music but before any music starts. I’ve never heard less chatter in a bigger room than I did in a 5,000-capacity club waiting for a Mitski show to begin. Hardly anyone was drinking. Hardly anyone was speaking loudly. No one was screaming – and I know they could have done, because later there was screaming after each song Mitski played like it was Beatlemania. But following those brief collective yells, the audience would again lapse into silence while waiting for the next tune.

The intimacy that Mitski can project, and use to connect with fans, is remarkable - especially in such a large venue. But there was an isolation to Mitski on stage that I found a bit chilling. On the tour I saw, the band was in a wide circle of darkness around a central, dramatically lit platform for the singer. It was impossible to see any interaction between the musicians because of the staging. And there was no visible interaction between the singer and the band. All the focus was on the connection between the singer and the listener. Each listener, as floodlit in their feelings as the singer appeared to be on stage.

Another trend I’ve noticed in live performance is the increasing prevalence of backing tracks. Laptops are everywhere on stage these days, of course, and not always playing prerecorded backing tracks. But many are. There are sounds that no one on stage is making, even when there are multiple live musicians. And then there are more acts than ever without any band, just singers with tracks. I was watching one soundcheck the other day – after a while, they started a song and simply walked off the stage to see how everything was sounding from the audience’s point of view. It seemed like the physical analogue to checking one’s own Instagram post.

If performance projects a social situation, what I see projected by the solo artist with a band in the dark, or by a solo singer with backing tracks, is a society of individuals supported by the labor of others – other people if they can afford it, and if not then purely by devices. I’m not making a musical judgement here – individuals can make great music this way, and do. But I feel I can venture a societal judgement, because I believe individuals cannot make a great society without other people recognized fully.

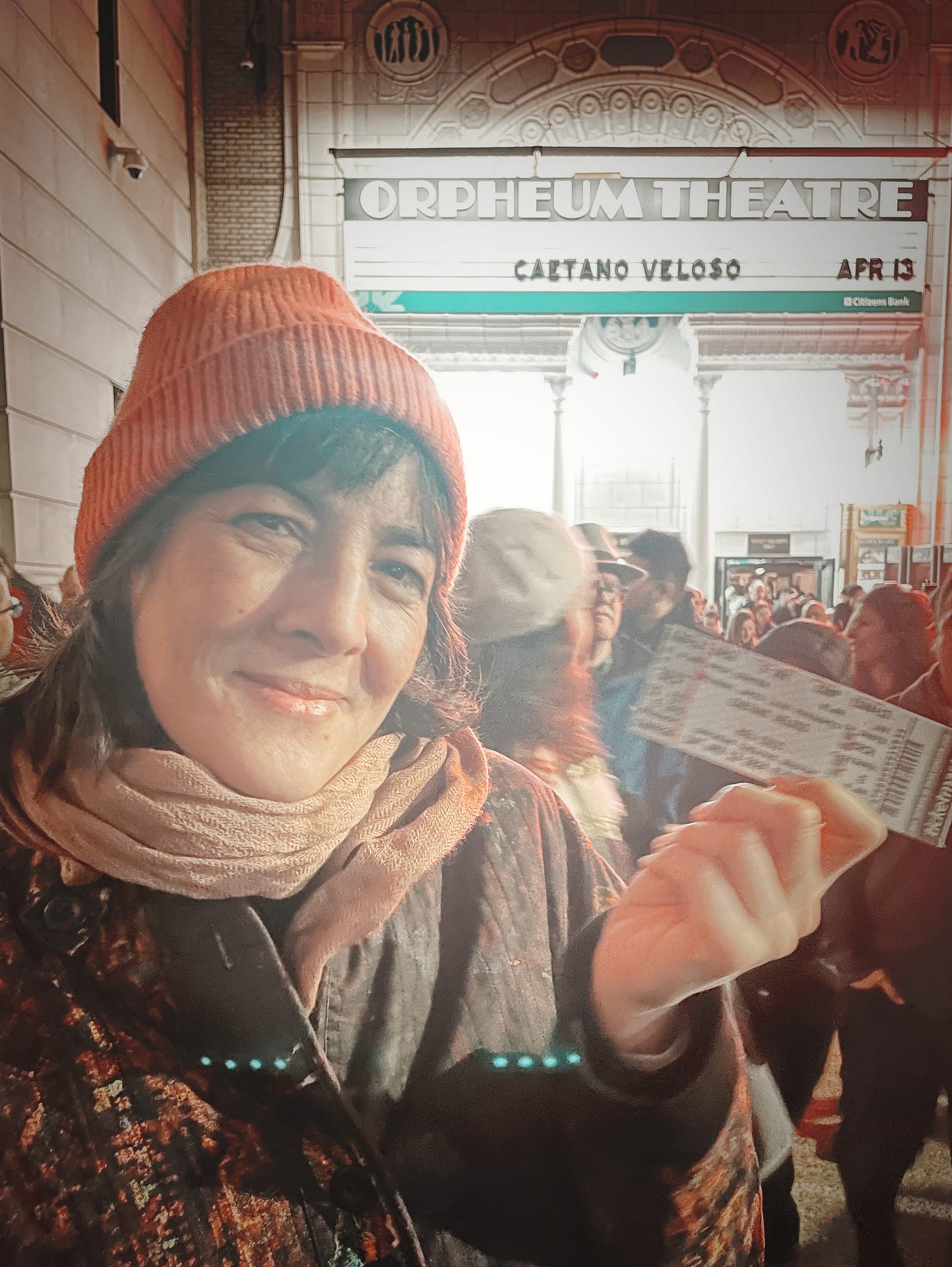

I experience the opposite of this from musicians often, but two recent performances stand out – one at a big theater, from the veteran performer Caetano Veloso who is a true star and has every right to bask in the solo spotlight. Yet Caetano took pains during his show to highlight all the great musicians in his band, to name them, to put the spotlight on them, even invite them downstage to dance. More to the point, he enjoyed their playing throughout – his joy in their work was visible from the audience. No one in that house left unaware of the labor of the musicians on that stage, and how special each was. To underscore the point, before the curtain went up an announcer read every person’s name who had worked on the tour, together with their job – from drivers and roadies to publicists and designers. It was a remarkable gesture to the many people it takes to put a star at center stage.

The other performance was in a typical Boston rock club, where Julia Holter stopped on tour last week. The band was relatively small – a quartet, with Julia on keys and vocals, her partner Tashi Wada on synth (and occasional bagpipe), Dev Hoff on fretless electric bass, and Beth Goodfellow on drums and backing vocals. But this was no simple rhythm section support for a singer-songwriter. Similar to Caetano, Julia’s pleasure in her band was visible throughout, and so was the space she had given them to put their all into the arrangements. Dev Hoff’s bass was played as a solo instrument as often as not, and Beth Goodfellow conjured an orchestra’s worth of dramatic settings from a four-piece kit (plus an ingenious use of triggers). Tashi and Julia’s sounds often merge, as partners will, but can also diverge when the synth or bagpipes leap to unexpected frequencies. It was a tightly structured set, yet full of surprising turns befitting Julia’s unique sense of melody and song structure.

And at the end, all four took the bow together.

This, to me, is a model of music I want to take out of the venue and into the street. It’s not music as virus, which is perhaps why it isn’t always communicable. Instead, it’s music as exchange. It’s music as valued labor. It’s music that projects the society I want to live in.

And yet it’s not the society we always have. Which is why I’m putting on another good record, and going to another good show as soon as I can.

Listening to: Beth Gibbons, Lives Outgrown

Cooking: Chinese chives, gift from a neighboring plot in our community garden

I love the title of this piece and the essay was just as good. I have nothing to add, but you have made me think. I will be rereading this. Thank you.

Well, audience chatter: I'll never forget seeing Tony Bennett at the Newport Casino, first night of the Newport Jazz Festival, and VIPs or other "premium" ticket holders, who had clearly been drinking heavily, basically shouting at each other through the whole performance. I remember thinking: I don't get it -- isn't this a major cultural event? Other end of the spectrum: the classical violinist Hilary Hahn conducting a master class at New England Conservatory and encouraging more physical cues between the student violinist and pianist. Not necessarily because they needed to communicate better with each other but so that they could communicate better with the audience. As another way to direct the audience's attention to the music. She made the point that audiences listen with their eyes as well as their ears. The following night, when I heard Hahn playing with the BSO, for those extended passages when she wasn't playing, she would often look at various sections or individuals in the orchestra, looking gratified at what she was hearing, but also directing the audience's attention. "This isn't just me up here -- it's the BSO, it's Brahms." ..... Sorry, once again I'm a bit off point. Thanks again for your valuable insights, Damon.