Beat of the Traps

Fake Artists, Real Songs, Fake Songs and Real Art

Am I a fake artist?

The digital world sometimes seems to invite this question. Imposter syndrome exists offline, of course; although personally, I’ve always found gigs a useful reality check. Am I really on this stage? Yes. Am I going to sing for this audience? Seems inevitable. Will they listen? Either way, we’re about to find out…

Online, it’s easier to construct a persona that never has to face such a moment of truth. Catfishing is one well-known result. So are trolls. So are some rather successful musicians such as Ekfat, a “Verified Artist” with a blue check on Spotify, whose tune “Polar Circle” was streamed 3.5 million times after being featured on a couple of Spotify-curated playlists with hundreds of thousands of listeners, Lo-Fi House and Lo-Fi Café.

Here is Ekfat’s bio on Spotify, “posted by Ekfat”:

“Ekfat is the moniker of Guðmundur Gunnarsson the upcoming Icelandic beatmaker that is part of the legendary Smekkleysa Lo-Fi Rockers crew since 2017. Ekfat is a classical trained musician that for years studied classical piano and flute at the Reykjavík music conservatory. Ekfat enjoys steady airplay in the domestic radio channels and is well-known for his detailed sound sculpturing in the Lo-Fi genre. In 2019 Ekfat moved from only releasing music on limited edition cassette tapes and can now be enjoyed by a wider public at the usual streaming outlets.”

Bully for the classically trained yet determinedly lo-fi Guðmundur aka Ekfat. Still, it might be difficult to deliver these congratulations because, as the Swedish newspaper Dagens Nyheter discovered, “The music collective Smekkleysa Lo-Fi Rockers does not exist but appears to be a fantasy that takes its name from the (real) Icelandic record company Smekkleysa. There is also no musician named Guðmundur Gunnarsson who calls himself Ekfat. The real Guðmundur Gunnarsson is an electrician, union leader and father of the artist Björk.”

And the real Ekfat…? Nothing to do with Björk, the Smekkleysa label, or Iceland at all. According to Dagens Nyheter’s investigations, “Three unknown songwriters from western Sweden are behind the songs of Ekfat. In various constellations, these authors are behind songs for another 89 artist names on Spotify, [all of] which DN can link to Firefly Entertainment,” a company based in Karlstad, Sweden. Karlstad turns out to be a hit factory of sorts. Another of Firefly’s stable there is, according to Dagens Nyheter, “The sole author of songs by at least 62 artist names. In total, they bring him 7.7 million listeners a month on Spotify, more than twice as many as the Swedish star Robyn.”

Or as Firefly’s website puts it, “We do not just release music, we create artists.” (Do they realize how accurate a statement that is for what they truly do?)

These revelations are only the latest in what is now a years-long scandal about “fake” artists on Spotify, first broken by Music Business Worldwide in 2016: tracks listed under pseudonyms that have no life offline, and no other online activity apart from their presence on Spotify-curated playlists. It seems obvious that there is a financial motivation for such shenanigans, though how it works hasn’t been fully proven. It is possible that these tracks are commissions, owned outright by Spotify (another Swedish newspaper, Svenska Dagbladet, claims to have found a smoking gun for at least one instance of this); and/or cozy deals with cronies (Dagens Nyheter’s exposé includes personal links between Firefly Entertainment and Spotify via executive Nick Holmstén, and Music Business Worldwide has found ties between another company responsible for many of these fake artists, Epidemic Sound, and Spotify CEO Daniel Ek himself); or there might be other, as yet unnamed ways they game the streaming system at the expense of “real” artists.

But what is a real artist?

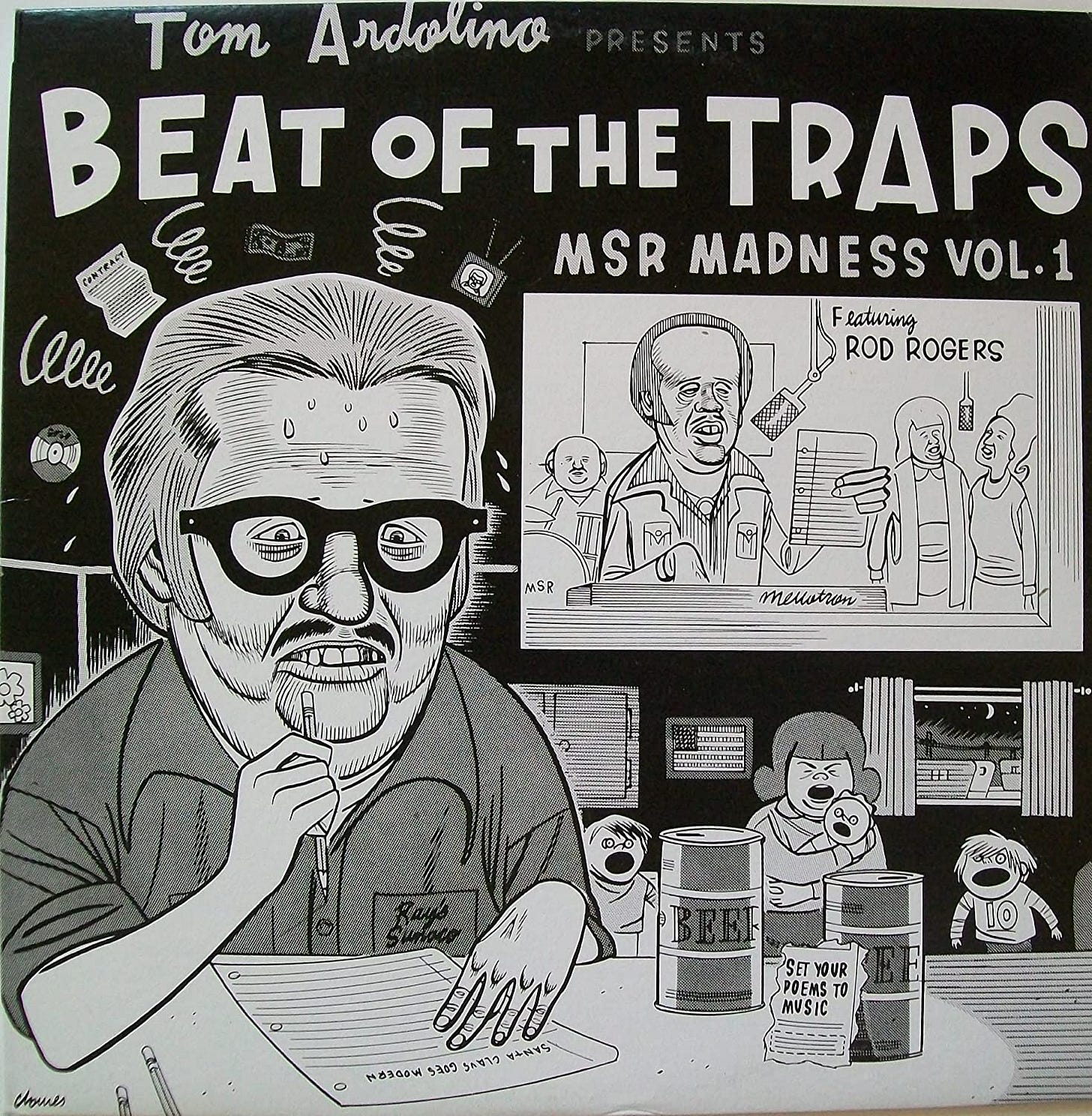

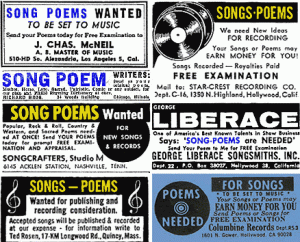

I’m reminded of an earlier version for what some might call “fake” artists, the pseudonymous creators of American Song-Poems collected by Tom Ardolino on his influential compilation LP Beat of the Traps. “The ads in the back of magazines would say ‘Send us your poems or song lyrics and we'll get them recorded. Big money could be yours!,’ or some such come-on. What it turns out to be is that you pay them to put music to your words, then they send you a couple of copies of it on their label,” explained Ardolino in his liner notes. “Sometimes the song would be pressed on a 45, sometimes on an album collection, maybe with a picture of the house composer to help convince the customer that they're legit.”

Song-Poems are no more real, you might say, than Firefly Entertainment’s tracks uploaded to Spotify. And yet… Ardolino heard a lot more in them than a cynical reproduction of mood or style like “Lo-Fi House.”

“Wild music; crazy lyrics. Beautiful music; perfect lyrics. You get all this and more with these kinds of records. Strange sounding cheap early electronic keyboards like the Mellotron; out of control drum machines. Normal-sounding budget session musicians; drunk - or something - sounding session musicians. And singers who usually sound like they never saw the words to the song until the recording light was on. They probably recorded 50 of these ‘songs’ in one day, sometimes using the same track more than once. It is this kind of set-up that can produce innocently beautiful works of art.”

Ardolino didn’t hesitate to call these recordings art – though he did feel compelled to put the word “song” in quotation marks. A song doesn’t always line up with our ideas of art. But it does, I suppose, imply something about craft. And while the tracks on Beat of the Traps are undoubtedly art for Ardolino (and many others), maybe they aren’t quite “songs” for that reason.

Song-Poems are like the inverse of tracks by streaming’s “fake” artists. Ekfat and his ilk most definitely make songs – that business about a conservatory background may be fiction but at least it’s believable. Yet I have a hard time imagining anyone considers them “art.”

So if “fake” artists like Ekfat can make real songs, and “Do You Know the Difference Between Big Wood and Brush” is a “song” but real art… where does that leave my own lo-fi recordings?

I know what I hope them to be: Cause brush always seems to burn out, but big wood keeps burning on. “Fake” artist tracks slip by on playlists because no one is really paying attention to them - if there is an imposter syndrome for fans, I would think those playing “Lo-Fi Café” must suffer from it. And I’d trade any millions of passive, half-conscious streams for committed listeners like Tom Ardolino.

Listening to: Over Fields and Mountains, by Branko Mataja

Cooking: Japchae with burdock and tofu

It seems the biggest question is how much does an actual human person have to be involved for something to count as art? The 20th century has seen a number of art movements, not only in music, which stretch the limits of what is acceptable in that regard. Do Steve Reich's tape-loop pieces count as art? What about Eno's generative music? I've worked in the ambient genre for a while, and I know it is very easy to create a system which will crank out music with minimal involvement.

I suppose it is all in the ear of the listener. If Ekfat's pieces sound good enough for someone to enjoy them, even after learning the truth about who Ekfat is, that surely counts for something. If a large corporation is profiting off of the assumption that Ekfat et al. are real artists, that is another issue . . .

Very thought-provoking essay, thanks for writing.

Fake? Hmmm. I recall the day we first replaced a famous freak of a drummer with a sample. Expedience and economy ruled the musicians in the trenches then. Fame is its own business model defying definitions. Other adjectives are fun discussions like the one I heard from Jarrod Lanier, composer among other things, who said 1% of the new accounts on Facebook in 2020 were human beings. “Fake” looms over the digital age. And with the ones and zeroes at the wheel, this ride is going to get even wilder as meaning suns on bias beach.