I went to see the new Led Zeppelin documentary, Becoming Led Zeppelin. It rocks.

That may be all the publicists for Sony Pictures Classics prefer be said about it. Zeppelin was never a critic’s band - they were widely ridiculed by the press in their early years, and those dismissals never quite wore off. They also left their mark on the band, as contemporary interviews with surviving members in the film make clear. Shock at their bad notices still registers 50 years later, as does their indignance at them.

I can’t accurately quote words spoken by the band in the film (and the only words in the film are theirs), because Sony Pictures Classics won’t provide a transcript or screener for me to use in fact-checking. “Word of mouth” always worked best for Zeppelin, as the band members explain in the film – regardless of what was being written about them, people who saw them play told others to go see them play.

As did I, in 1977. I was thirteen years old, and their Madison Square Garden concert left such an impression on me that I still want to drum like John Bonham, even though I’ve never played hard rock and at this point might as well admit I never will. It also remains the only arena rock show I’ve ever seen where I felt I could truly hear and see the musicians play their instruments. They huddled together on stage, effectively treating that massive space like any other club. The area they took up was just enough for drums, bass and guitar, plus a little extra wiggle room down front for the singer. It doesn’t seem possible, given what I now understand about sound systems, but I could swear I heard their instruments directly off the amps and drums that night.

In the film, they describe this spatial arrangement on stage as a deliberate response to their early poor reception by critics and audiences alike. On their first tour of the USA, opening for Vanilla Fudge and playing to partly empty houses, they decided to keep as tight together on stage as they did in rehearsal. Page says he urged the group to pay no mind to the audience, and simply play to and for one another.

It worked, obviously. The film’s arc ends with a triumphal run of packed headline shows in the US, crowned by their first gold record and a sold-out homecoming gig at the Royal Albert Hall in London, January 1970. This was clearly such a satisfying riposte from the band to their early critics that they still, after all that was to come, make it the ending for this officially sanctioned documentary. It doesn’t really matter what happens after that, does it, says Robert Plant in the film. It’s like a rock-and-roll version of Tolstoy’s maxim that, “All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” Not that Becoming Led Zeppelin is a Russian novel; on the contrary, the band chooses to tell only the happy part of their story, the one that resembles every other band’s happy story. They leave out the dark, peculiar-to-Zeppelin bits. Which is also why the film was such a joy for me to watch, and likely will be for many musicians whether they are fans or not. It’s a portrait of the happy ways we are all alike: discovering a sound we can make with friends, forming a little gang against the world, and miraculously finding that the world responds. (A part of the world, for most of us. And most of the world, for a band like Led Zeppelin.)

But I want to highlight something peculiar about themselves that the band does include in the film, which is how they maintained control of their recorded work even as they dealt with the most powerful players in the music industry. Because whatever you feel about their music (and I’m telling you, it f’ing rocks), their business sense in the late 1960s seems as much of the moment for musicians today as ever. Led Zeppelin, for all their boomer rock-god posing and famously chaotic behavior on tour, had it supremely together when it came to watching over their rights. And they did it by producing their own recordings, and owning their masters.

Becoming Led Zeppelin was made with the band’s participation, so the story it tells is obviously the story they want to tell. And it’s Jimmy Page, who was not only the guitarist but the producer for the band, who takes charge for the portion about their masters. He explains that when Led Zeppelin started, he was determined not to tie their fortunes to the success or failure of radio singles – this was how the industry functioned at the time, and he says he felt his previous band the Yardbirds had fallen apart due to those pressures.

Instead, Page says, he wanted Zeppelin to be an album band exclusively. He wanted the radio to play entire sides of their LPs, not single tracks. And some did, enthusiastically, though it was only possible on the newly established free-form FM stations in the USA. He claims he wasn’t interested in catering to the rest of the radio dial… which ruled out the dominant commercial format not only in the US, but in all countries including their home the UK.

This uncompromising position was made possible, according to Page’s own account, because he not only produced but paid for the recording of their first album. The band completed that master – mixed and sequenced – before even entering into negotiations with record labels for its release. In the end, when Atlantic signed the band for a then-staggering sum, Page delivered the album for release without any possible alterations. According to the film, Page and the band’s physically gigantic, elaborately mustachioed and famously intimidating manager Peter Grant flew to New York with the finished master tapes in hand, to deliver them personally on signature of the contract.

For the second album, Page says that he was no less self-sufficient. He again produced the album, as he did for all their eventual recorded work, and in the film claims that he deliberately sabotaged its most commercial track for radio, “Whole Lotta Love,” by inserting a riff- and melody-free sound montage in the middle of the song. Again, he wanted an entire album side broadcast, or nothing at all.

Jimmy Page’s hostility to singles is especially remarkable, given that today it is nearly impossible not to hear Zeppelin songs on commercial US radio. Indeed, Naomi and I have a standing challenge with each other to try and cross the entire state of Connecticut by car without hearing anything other than Zeppelin, by flipping the dial as one track ends to find another playing on a different station.

But that’s only possible now because Page’s idea of the album as the crucial format for his music was, to cast it in contemporary terms, a canny read on the future of music technology. During the 1970s AM radio, with its hit parade, eventually gave way to FM and what would become called, “Album-Oriented Rock.” Page saw that very early as a new paradigm, and consciously worked to situate Zeppelin within it. For a group that played the blues, it wasn’t an obvious choice – they weren’t the Beatles or the Beach Boys, experimenting with pop form. By comparison, Zeppelin were closer to a bar band, playing covers and old blues (while copyrighting them for themselves whenever possible, another extraordinarily canny business move). Not the ones you’d expect to break new ground for the structure of music distribution.

Page was right that it was the album which would dominate the entire industry for the next thirty-odd years. Producing their own recordings and owning their masters before signing a deal gave Zeppelin the leeway to act according to their idea of music business future, rather than music business past. Those at the top of the industry are the biggest achievers from former paradigms, by definition. Even when musicians see through that – which they often do, especially given their youth - they rarely win the freedom from industry partners to act on it. Today, in a moment when current paradigms in the music industry seem especially fragile if not doomed, Zeppelin might be something of a model in the way they worked to dictate terms which would function best in what they saw as the next phase for music distribution.

A bet on the album format won Zeppelin fame and fortune. That, plus their remarkable live performances. Cause did I mention that they rock…? Go see the film if you don’t believe me.

Listening to: Passivité by You Ishihara

Cooking: sweet popcorn

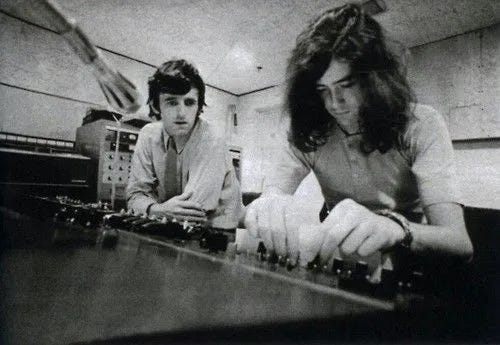

It’s definitely, absolutely, NOT, in any way shape or form, Eddie Kramer. It’s an F-up. Don’t know how it happened. Not sure who that is pictured with Jimmy Page; but again, it is positively NOT Eddie Kramer.

I tried to post a photo of Eddie Kramer with Jimmy Page at the mixing board but it doesn’t allow photos here. Please give me an email address, if you don’t mind, and I will forward.

Yes! Traveling through *all of New England* and *never* running out of Led Zeppelin on the FM dial!