Last week, Representative Rashida Tlaib formally introduced House Concurrent Resolution 102, “Expressing the sense of Congress that it is the duty of the Federal Government to establish a new royalty program to provide income to featured and non-featured performing artists whose music or audio content is listened to on streaming music services, like Spotify.”

The Resolution was co-written by UMAW, a group of independent musicians and music workers. And it seems to have taken a good part of the music industry by surprise. Both Rep. Tlaib’s office and UMAW have been fielding calls from professional music industry lobbyists in DC ever since the Resolution dropped. Where did this come from, several have asked.

The answer is simple, although it doesn’t seem to be the kind of reply they were looking for: It came from the experience of being a working musician.

The music industry is notoriously complicated. There are a hundred years of overlapping and sometimes seemingly contradictory laws and practices that make it difficult to even chart all the ways money flows from recordings and its various uses. To start with, there are separate royalties due songwriters (and their music publishers) and recording artists (and their record labels), even when those people are the same and even if the publishers and record labels are owned by the same corporation. In addition, there are separate performance royalties, satellite and internet radio royalties, synchronization rights, and others I’m forgetting but by now the edges of my cocktail napkin have run out.

The music industry is also notoriously consolidated. There are only three major labels left (Universal, Warner, and Sony). There are five platforms that control 80% of streaming, globally (Spotify, Apple, Amazon, Tencent and Google). There are just two live music promoters responsible for 90% of that segment of the industry (Live Nation and AEG). And if you approach the business from the point of view of these outsized players, there are essentially three locations that comprise the entire music industry in the US: New York, Los Angeles, and Nashville.

So how did Rep. Tlaib (from Michigan’s 13th congressional district, Detroit), and UMAW fly under the radar? Very, very easily. Neither of us fit the profile that defines the music industry for itself. Which is precisely why we need to be heard.

There are loads of musicians everywhere in this country, playing musics that don’t even have Billboard charts, much less make them with a bullet. There are loads of music labels apart from the majors, and music promoters outside Live Nation and AEG. The business is in truth so much bigger, and broader, and more diverse than the “industry.”

Since Rep. Tlaib announced her Resolution, UMAW has been asking supporters to write their district’s congresspeople and urge them to cosponsor. More than 10,000 letters have gone out – and they’ve come from all 50 states (plus DC!). I’m looking at the spreadsheet sorted alphabetically by location, and starting at the top there are letters to five of the seven congressional districts in Alabama. There are letters to all nine of Arizona’s congressional reps. To three out of the four from Arkansas. And so on, and on, and on. The whole damn country is filled with musicians, music workers, and music fans who care enough to write Congress about it.

And yes, there are many, many letters from New York, LA, and Nashville.

There’s another way Rep. Tlaib’s proposal has taken the industry by surprise: it’s a very simple idea. Streaming platforms make use of recorded music, so streaming platforms should pay something directly to all the musicians who record that music.

This is not rocket science. But you’d think it was the most bizarre idea ever if you talk to some people steeped in the way that the music industry functions financially.

Take Spotify. They dominate the streaming industry (31% of global paid subscriptions), but they won’t even say what they pay for streams. Their accounting system is so confusing, they built a public-facing website called “Loud & Clear” just to try and make it more understandable. Here is how they answer one of their own FAQs, “Why does the ‘per stream rate’ appear lower for Spotify than some other streaming services?”

Got that?

Spotify, like many in the music industry, speak the language of capital investment. Not a per-stream payment, but a “revenue-to-streams ratio” – and so forth. You can puzzle it out if you want to spend time cutting through the jargon.

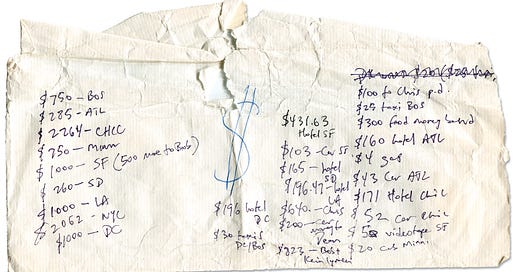

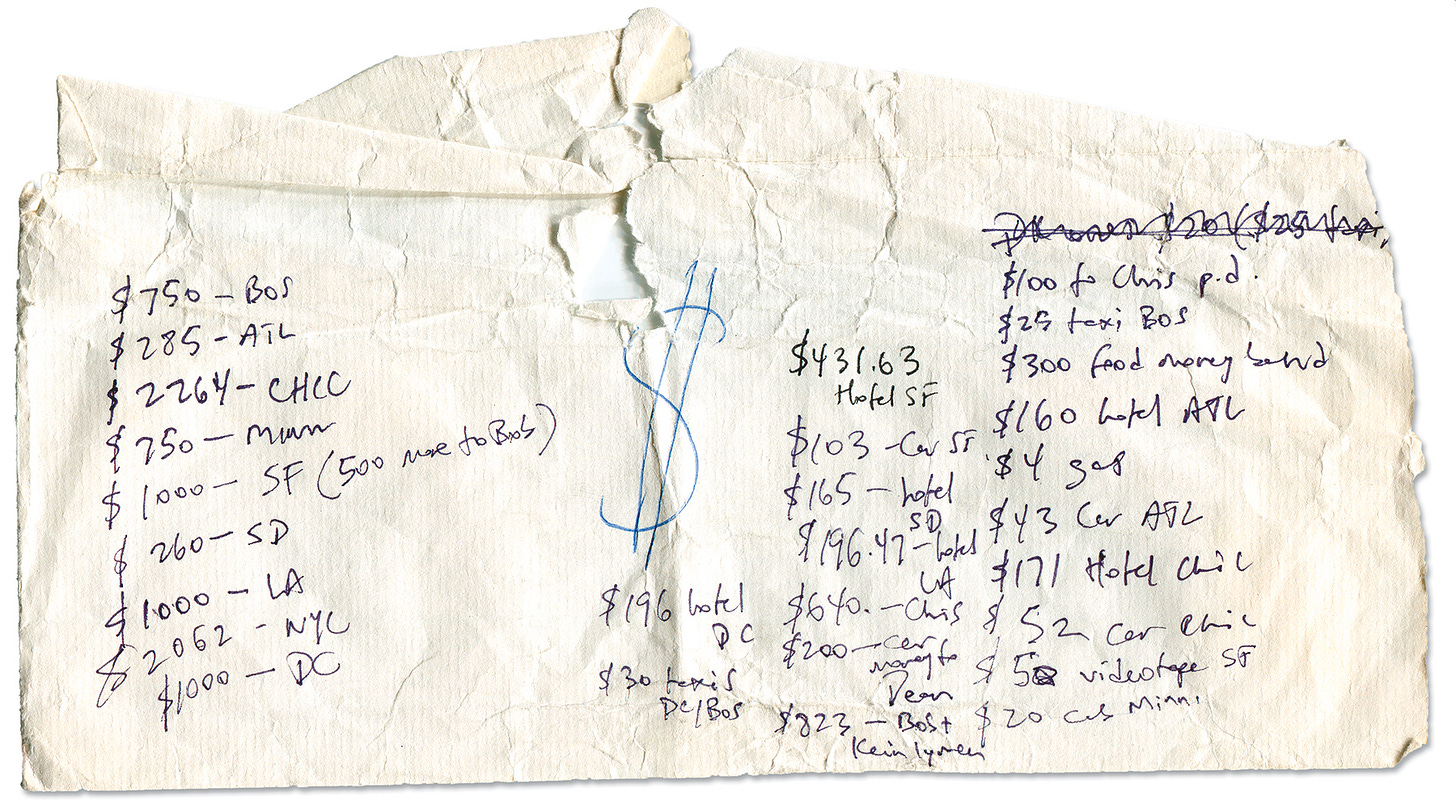

I’ve been a musician for many years, and that’s not the way I learned to do business. Maybe a Spotify employee would dismiss it as primitive, but here is an example of real-life music business accounting from my own history.

That’ll be cash on the barrelhead, son. Not part, not half but the entire sum. No money down, no credit plan. No time to chase you, cause I'm a busy man.

I’ve always wondered why Gram Parsons chose to include a fake live recording on what became his final studio album, 1973’s Grievous Angel, pairing a raucous cover of the Louvin Brothers’ Cash on the Barrelhead with his own gorgeous ballad Hickory Wind. Was it to capture the mood of his live performances? To slip the song he had previously given to the Byrds on to one of his own albums? Or just to showcase the killer band he had put together for this recording, a group he could never take on the road cause they were Elvis’s backing band, no less, and plenty busy: James Burton on guitar, Glen Hardin on piano, Emory Gordy on bass, Ron Tutt on drums. The TCB Band, as they were dubbed by Elvis – Taking Care of Business.

Real-life music business: the players in the TCB Band would never have received any royalties for their work on Grievous Angel, or on Elvis’s number one 1973 album Aloha from Hawaii Via Satellite (now 5x platinum), or any other they recorded. They are “non-featured musicians,” as the industry knows them, meaning they didn’t have a contract with a record label, or a music publisher, to receive any of the streams of income the industry has historically assigned from recordings.

Until, by an act of Congress passed in the late 1990s, satellite radio was required to pay these recording musicians something directly. That new royalty for a new technology was the first accounting non-featured musicians had ever received for use of their recordings in the US.

And now, by an act of Congress that Rashida Tlaib and UMAW are working to create, streaming platforms would similarly be required to pay something to these and all recording musicians directly. Cash on the barrelhead. TCB.

Listening to: Širom, The Liquified Throne of Simplicity

Cooking: Romano beans, boiled a bit longer than they should be, dressed with olive oil, salt and tarragon

Sent the letter to one complete asshole and two pretty ok folks. Thanks for doing this! (Also, thanks to you and Naomi for Exact Change. Those books blew my college mind some years back.)