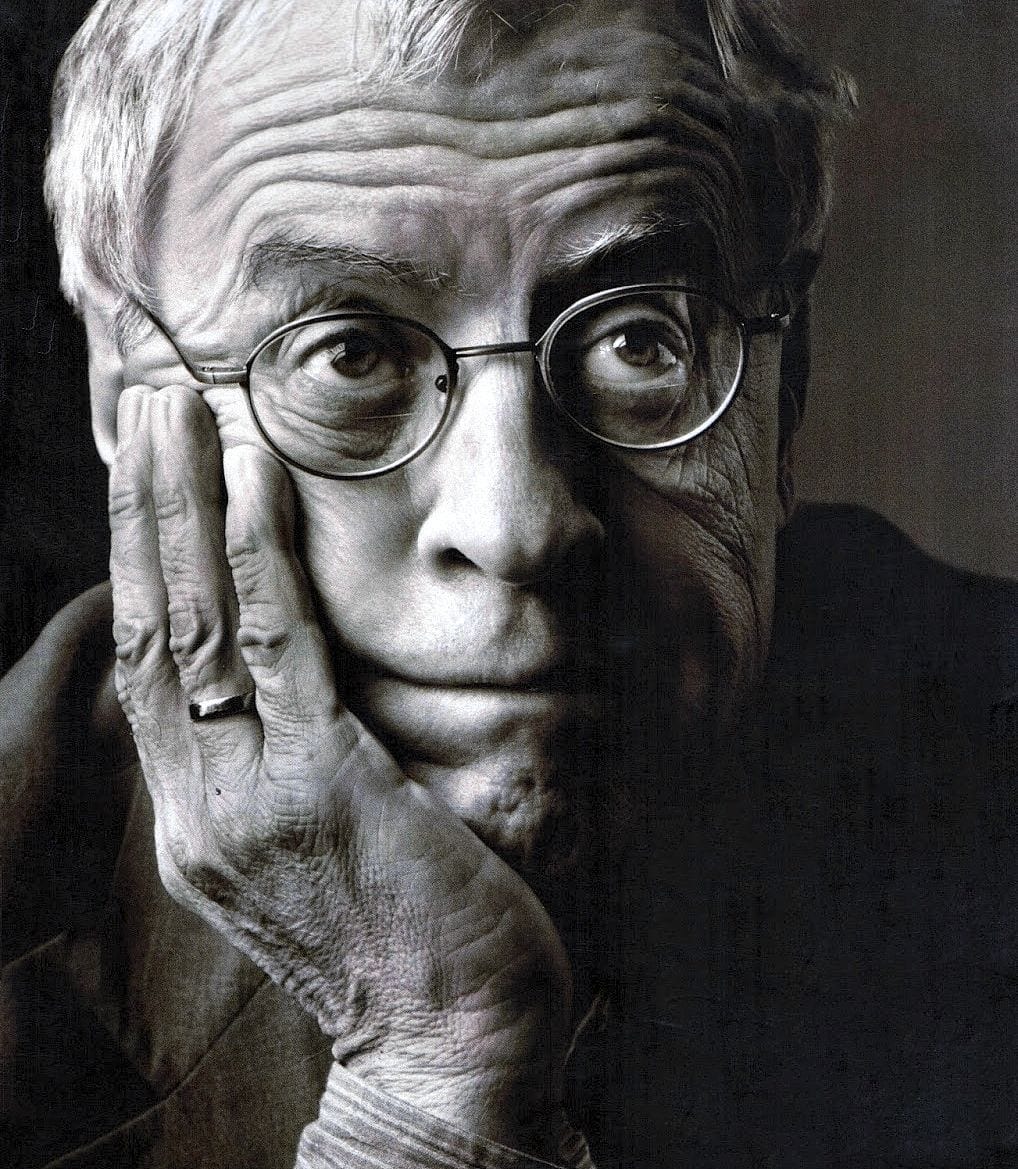

Charles Simic

In memory of a master teacher and writer

I was an undergrad at Harvard when I read on a book jacket that Charles Simic taught at the University of New Hampshire. I called up and found that you could register and pay for just one course at a time there, so I did. I drove up weekly all semester from Cambridge and took his poetry workshop – once, twice, and then he said no need to register again, I could just drive up and meet him in his office. So I did.

He taught by example. The lesson was: enjoy life. Enjoy books. Enjoy food. Be in love. Be miserable. Enjoy that, too.

Naomi and I made a zine together called Exact Change, and I brought him a copy. He enjoyed it. Then he took a manuscript out of a filing cabinet. Have you ever thought of publishing a book, he said – my publisher rejected this, because it is prose poetry and they don’t want prose poems. Take it home and see if you like it.

We loved it. We decided to start a publishing house. Naomi had already designed the book when Charlie told us his publisher changed their mind – they wanted the manuscript after all. It won the Pulitzer Prize.

We started the press anyway. Charlie gave us a different set of poems, which became our first publication – an oversize chapbook called 9 Poems: a Childhood Story.

Charlie’s childhood had been in Eastern Europe during World War II. So had my father’s. But my father never made black jokes about it. Charlie’s humor didn’t just make me laugh, it felt forbidden.

A student wrote a poem about a swan. Charlie said: “No one has been able to make a poem about a swan since the 16th century. You can’t write about a swan now. Come to think of it, if someone did manage to make a poem about a swan today, that would be a triumph. This isn’t it.”

I left class early one evening to get ahead of an approaching snowstorm. Charlie said: “There are at least two nights every year when I’m driving home and think this is it, I’m not going to make it. This will be one.”

“You haven’t read Rimbaud,” he said to a student who hadn’t. “You haven’t lived.”

On gourmets: “They wouldn’t dare eat a slice of greasy, garlicky sausage. With a knife.”

Naomi and I would drive to visit Charlie and his wife Helen at their house. They served wonderful simple meals – Charlie relished them. Once we delighted him by bringing a bottle of Simi Valley wine with a doctored label: Naomi had added a “c” to “Simi.” Charlie didn’t want to open it, he wanted to leave it casually in the kitchen so it might catch someone’s eye and confuse them.

When Yugoslavia dissolved and many predicted religious civil war, Charlie told me that couldn’t possibly happen because Serbs are the least religious people on earth. He said Serbian mothers wouldn’t let their sons be soldiers, they would drag them home by their ears instead.

But the war did happen, in the ugliest way. Charlie’s mood darkened. He seemed depressed to me in those years.

It was right around this time that Naomi and I also went through a depression - our band had broken up and we quickly tried to start a new one on the rebound. We went to Vermont to record a demo and unexpectedly stayed an extra couple days to finish it.

While there we suddenly realized: we have a date with Charlie and Helen in Boston. We were to meet for drinks on a Sunday at the Ritz. It was Charlie’s idea – they were going to be in town, and he said we should meet for a drink on a Sunday at the Ritz. No rhyme or reason – just to delight in the idea of meeting for a drink on a Sunday at the Ritz.

This was before cell phones. We couldn’t reach them to explain, and it was too late to get back to Boston in time. We had stood them up.

When we eventually did explain, all of us back at our respective homes, Charlie was patient but it was clear it wasn’t a funny enough mistake to be truly excused. We felt young, foolish, and terrible. (The demo didn’t work out, either. Both remain painful memories for me.)

Our relationship never quite picked back up where it had been. We continued to see Charlie and Helen, but the carefree nature of our visits seemed to have changed. Eventually we kept in touch more by call and card, and then those grew less frequent.

I never stopped thinking of his lesson by example, however. I assumed, and hoped, he was enjoying everything – food, books, love, misery.

Charlie used to tell me, about my writing: don’t be in such a rush to finish. I was confused at the time because his own poems were so short – hadn’t he stopped them abruptly?

It was only much later that I realized those surprise endings of his aren’t a stop at all, they are a turn back to the poem as a whole.

Beautiful piece.

Thank you for this. I was a UNH student 1993-97 and currently work there and he was an amazing, talented and wonderful person.