Click Wheel of Fortune

Apple discontinued the iPod this week, sparking nostalgia for many whose personal musical history was entwined with the device. Rob Sheffield wrote a particularly emotional and hyperbolic reminiscence for Rolling Stone: “The best damn listening device in the history of human ears.”

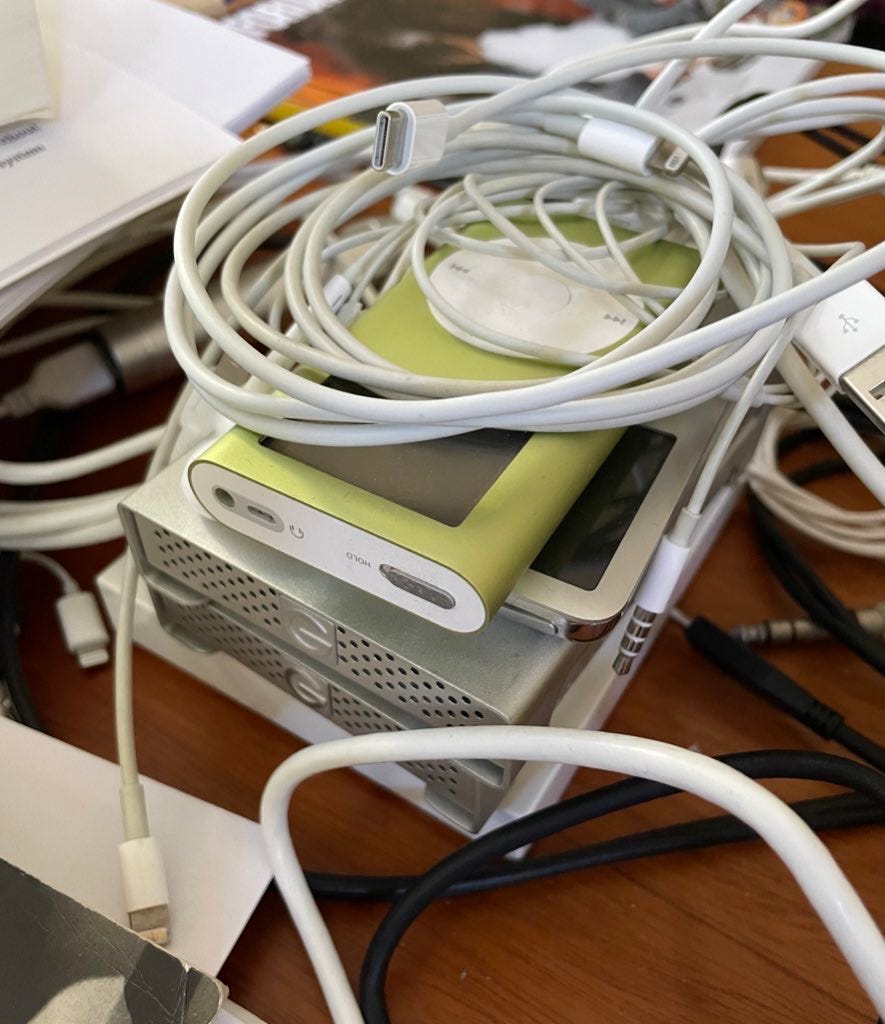

I’m not immune to the appeal of the object – I keep two on the desk where I’m writing this. The original, “classic” model in particular has an aura of modernity that keeps it looking futuristic even with technology wildly out of date. (No doubt designer Jony Ive intended from the start that it ultimately end up precisely where it is now, that is, the collection of the Museum of Modern Art.)

And yet… didn’t Apple’s entry into digital music destroy the market for physical media, break the power of the album, and lead directly to the streaming mess we’re in?

That’s all true. But if you look carefully at the history, I’d argue it wasn’t the iPod that did all this - it was the far less glamorous, and far more imperfectly designed iTunes Music Store.

These two facets of Apple’s takeover of recorded music at the turn of the 21st century may seem inseparable, at least in hindsight. But there was a full year and a half between the launch of the iPod (October 2001), and the launch of the iTunes Music Store (April 2003). The iPod could, and did, exist without the iTunes Store.

My own iPods are living examples of this. They are filled to capacity with digital music. But I know – because Apple’s software insists on keeping these sorted in their own special category – that I have only ever purchased 22 songs from the iTunes Store. 22 songs in nearly as many years. All those other megabytes come from CDs, downloads via other sources (both legit and bootleg), and my own music.

In other words, the iPod could be put to plentiful good use outside the specific environment Apple built for it. Which is maybe a definition of successful industrial design?

On the other hand, what the iTunes Music Store was built for is highly constrained, and nothing good. Yet that’s the part we’re stuck with. It continues as a store for digital content, and the design of its business is imprinted on streaming music platforms.

From the beginning, there was a fundamental divide between the economic functions of the iPod and the iTunes Music Store. The online store selling digital content was never intended to be profitable. Meanwhile, sales of the physical iPod and its successor the iPhone drove Apple’s expansion in the 2000s, taking it from a “struggling” computer company to the richest corporation in the world. Apple’s most successful financial model is actually very old fashioned: they sell gadgets at a profit. It could be any 20th-century industrial business.

The iTunes Music Store is all 21st century, however. For one, its financial model remains mysterious. When Steve Jobs was in charge, he insisted that the iTunes Store was not there to make a profit. This was so ingrained in Apple’s rhetoric that after the store’s incredibly successful first decade, analysts began to speculate that it was impossible it was still only breaking even at best. “The business has grown so rapidly however that its profit-free nature has come under severe pressure,” wrote one wry observer. Currently, the monopolistic model of the iTunes Store offshoot for apps and games, the App Store, is the subject of both governmental regulatory inquiry and civil lawsuits, most notably from Epic Games. It seems obvious that market control via the iTunes Store and App Store has led to all kinds of value for Apple… although how exactly still remains unclear, and controversial.

This push for value created solely by market control is, again, a very 21st-century strategy. The iPod itself entered a 20th-century market of competing hardware mp3 players, all of which had equal access to a variety of digital media formats. It was the iTunes Music Store that created proprietary advantages which led to market dominance for Apple – precisely the reason the store itself could be profit free, at least in theory. A loss leader to gain market share, and ultimately monopolistic control of a medium, which generates controversial and closely guarded sources of income… Beginning to sound familiar?

The pattern of the iTunes Music Store has been mimicked by streaming platforms, most especially Spotify. Spotify, too, insists that they do not turn a profit on the digital content they provide. It’s perhaps no coincidence that they have also continued the attack on the album and on physical media that the iTunes Music Store began. And of course they have contributed to the ongoing downward spiral of value for recorded music.

With faith in streaming platforms crashing at the moment – Netflix and Spotify have lost 70% and 60% of their value on the stock market this year, respectively – perhaps it’s useful to remember that these companies have copied only half of Apple’s original success with digital content. And it’s the half that was not intended to make a profit.

Maybe streaming music platforms should adopt the full model from Apple, and simultaneously work to sell well-designed objects with a simple profit margin. Like LPs, for example.

Listening to: Finding Home by Maya Youssef

Cooking: Everything in our freezer, which is even older than a first-generation iPod and has suddenly stopped working

For me, each medium is very different from the others. iPod is an iPod, and vinyl is vinyl, etc. I think the iPod is great, but in no way is it the same way as listening to music on vinyl, or CD. A different experience altogether. I think what happened to my original iPod is that I put too much music on it. I became a music hog! Vinyl is more minimalist (not physical space-wise of course) and simple life. There is side one, and then there is side two. The world is perfect again!

Yep - there’s a reason vinyl and CDs and even cassette tapes(!) are making a kind of “under the popular radar” comeback. Great post!!