Conceptual Music

Maryanne Amacher’s Writings

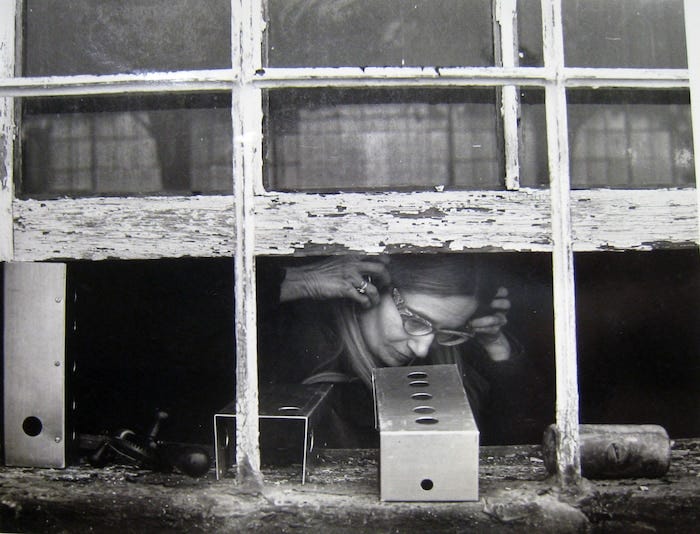

In one of the very few recordings composer Maryanne Amacher made available in her lifetime, she bangs on the walls and floor of the sacred cave under the Pyramid of the Sun at Teotihuacan, Mexico, with a bundt pan.

The gesture is, “As beautiful as the chance meeting on a dissecting-table of a sewing-machine and an umbrella!” But the resulting music is no Surrealist coup-de-foudre. Like all of Amacher’s work, it is a dense, slow unfolding of sound that is the result of a highly deliberate train of thought and research.

Still, what those thoughts were about has always been as difficult to access as her almost entirely unrecorded music. In the online era – particularly in this moment of streaming media – we take for granted that any music of interest is within reach. But what of music that isn’t made to be recorded?

Maryanne Amacher’s music lies beyond our technological reach. This doesn’t put it beyond imagination, however. On the contrary, that is where it lives. It is conceptual music, to borrow a term. Amacher’s ideas are the music, whether or not they were ever realized, or whether or not they ever could have been.

Which is reason to celebrate the publication of Maryanne Amacher’s Selected Writings and Interviews (Blank Forms Editions) as more than a volume of a composer’s statements. This book is Amacher’s music, as fully as we can experience it in her absence. It doesn’t contain scores – if she had simply written scores, we could play them. It does include denouncements of most every strategy we might take to try and reproduce her music in the present.

Not to say that Amacher was disinterested in physicality. Like her exact contemporary Robert Smithson (both born 1938), Amacher’s conceptualism was paired with a quixotic pursuit of grand realizations – some of which happened, many of which exist only as unfunded grant applications. Also like Smithson, Amacher was so intensely focused on site that its very terms begin to dissolve. In her early work, this took the form of pieces she called City-Links, where sounds from one part of a city might merge with another – not unlike Smithson’s “Nonsite” displacements. From Amacher’s description of the first in this series, In City, Buffalo, 1967:

“The FLOW of experience in the living environment – the in-and-out of a day’s movement from TV to car, to radio, to street, to office, to home, to store – the medium for IN CITY. Its space is Life Time. Where we RECEIVE. Rather than concert hall, room, location, gallery.”

Reaching for this flow of experience peculiar to a given site, Amacher rejects traditional physical spaces for her music. Rather than a concert hall, room, location or gallery, she chooses… what, exactly? It’s difficult to reconstruct. The schedule for In City, Buffalo, 1967, which took place over four days in October that year, includes notes for multiple locations – some of which seem to include sound (“skydivers perform with musical instruments”), some of which don’t (“WINDOWS, department stores; integrated: streets, sky”) – as well as radio and television broadcast. Did this happen? Does it matter? “None of it is to be thought of as an event or show, or even a happening,” Amacher explained to the local newspaper. “The idea is not to go some place at a fixed time and hear or see something. We want to transform the environments people live in into art.”

This dissolution of event, or splitting into event and what we might call nonevent, is reminiscent of the dialectic between site and nonsite for Smithson. Amacher’s nonevent made four days of Buffalo in October 1967 into a composition. But not one that can be recreated anywhere else, or at any other time.

The City-Links evolved into a series of audio displacements within cities, using telephone hookups to transport sound from at least two locations and link them together in a third. Hearing the Space, Amacher called this for an installation at MIT’s Hayden Gallery in Cambridge MA. “Hearing the space – what is distant and what is local, clearly and simultaneously,” she wrote in program notes. “Because of normal associations of seeing and hearing, continuous transmission provides a perceptual detachment not readily possible when physically at the site: a place memory is seeing in. Ambience and time become image. Perceiving aurally as ‘image.’”

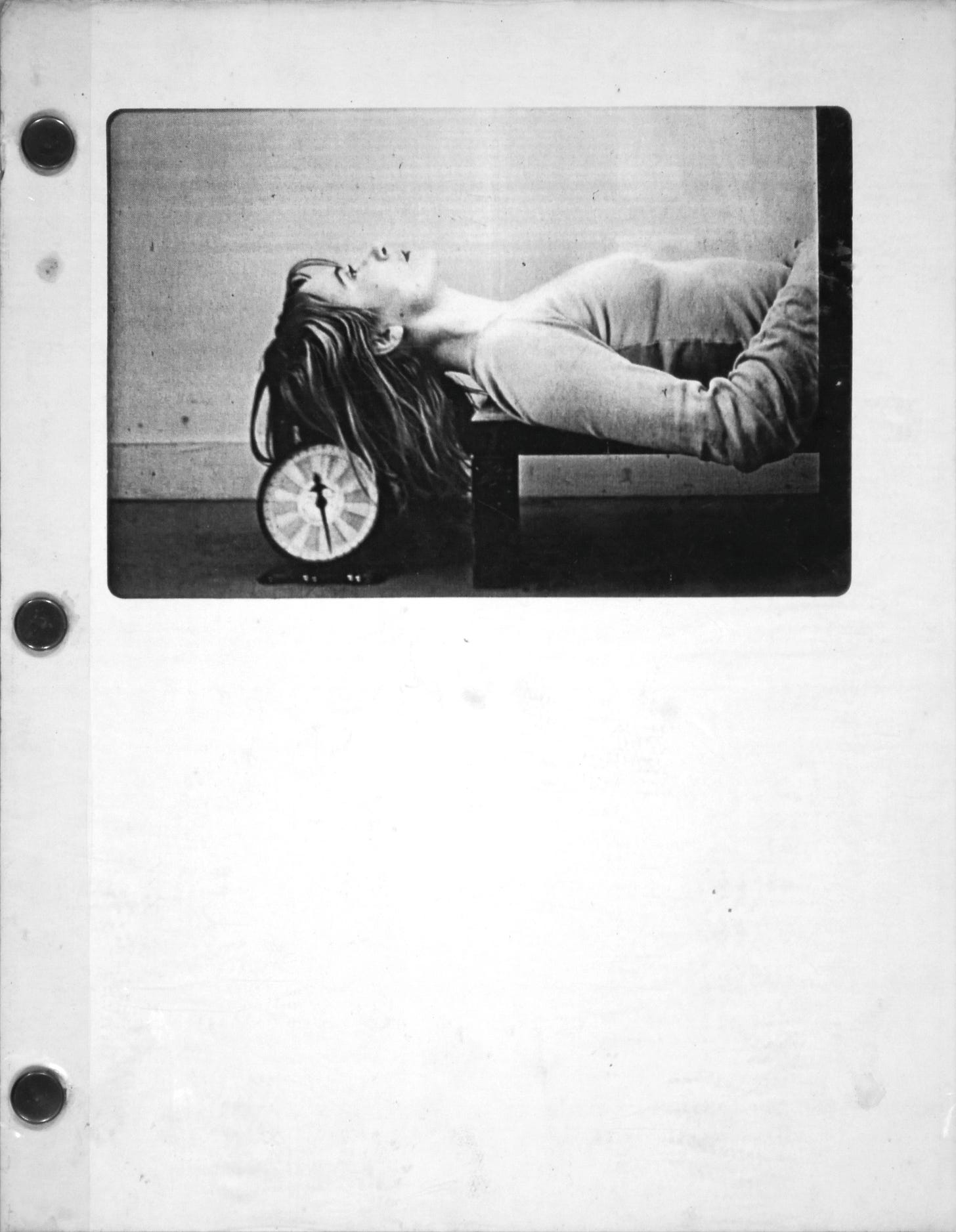

This idea of “seen” sound became increasingly central to Amacher’s work. Starting in the mid-1970s, she began to experiment with tones that might generate physical responses in the body other than what we think of as “hearing.” For a piece commissioned by the Merce Cunningham Dance Company, Labyrinth Gives Way to Skin, she wrote: “Work has been in bringing interpretation to perceptual levels, other than hearing, finding ways of letting hearing open channels to what was previously considered subliminal, and letting these impressions surface.” Or as she explained it in a later interview (1988), “Music is a very limited one or two ways of hearing… We walk out into the world and we have all these different experiences, of hearing things far away, and close up. We never learn about any of these things in our musical training at all…”

Here we see the connection between Amacher’s use of what are essentially field recordings – as in the City-Links – and what would become the focus of her later work, “otoacoustic emissions,” or sounds generated by the bodies of listeners themselves. “The kind of tones that we create within our ear and within our brain that are not the tones that sound in the room, but arise from them.” If the city at large provides more ways of hearing than music usually takes advantage of, perhaps music might be made to provoke those ways of hearing, too.

The pursuit led Amacher to another series of site-specific works she called Music for Sound Joined Rooms. “They are ROOMS to ‘listen to,’” she wrote – not to listen in. Using architecture, Amacher found she could project “structure-borne” sound throughout a series of rooms and “get the sound alive.” This gave her both the kind of “hearing the space” she had been after in the City-Links, and the extra-hearing responses she was interested in provoking with listener’s bodies. “I now believe that the architecture can make magnifying really expressive dimensions in music in a way that you can’t do any other way,” she told an interviewer.

No wonder Amacher largely rejected recordings as a satisfactory container for her work. She had technical reasons for this, as well. “THE GREAT MID-RANGE MIND” is how she dismissed the era of LPs, the dominant format as she came of age. “Like living in a basement cell, with constant artificial illumination, and never being able to experience the many changing degrees of light that our eyes/minds/bodies ‘enjoy’ recognizing.” (And they called it Hi-Fi!)

Amacher’s primary complaint about analog formats – LP and tape - were the limitations of its dynamics. When she worked with very low volumes, as in a piece she made for John Cage to accompany his reading of Empty Words, the “signals are most of the time below -40 on the VU meter,” she explained in a production note, meaning that any self-noises generated by the tape machines used for playback “become exceptionally audible” as “in no way are they masked by the music I will be producing.” At the other extreme, when she worked with very high volumes in later pieces meant to evoke otoacoustic reactions, there was no way to reproduce this physical intensity through the medium either.

For these reasons, Amacher eagerly embraced digital technology when it became available – on Super VHS, laserdisc, and CD. At the end of her life she was looking ahead to VR and its possibilities. Nevertheless, “My music is not conceived for playing in your living room,” she explained simply to an interviewer in 1991. Loudspeakers themselves presented a limitation she rejected. “I get this feeling like this monster is trying to get out of these boxes, you know?” she said. And headphones were even worse:

“It doesn’t excite me to be listening with headphones because I like to be standing, moving. When you move, your body hears differently: your skin, your ears, the whole neural-processing apparatus functions differently. The effect of sound streaming out of your head is lessened with headphones. I love the sensation that sound is coming with you, and at the same time you’re hearing sound elsewhere in the room, like a sonic wrap.”

In the liner notes to Sound Characters (making the third ear) (1999), one of two full-length albums she released in her lifetime – both are CDs on John Zorn’s Tzadik imprint - Amacher included listening instructions. “When played at the right sound level, which is quite high and exciting, the tones in this music will cause your ears to act as neurophonic instruments that emit sounds… These effects can also be experienced at a lesser volume – but the music loses its energy and takes on an innocent ‘ice cream man’ character not intended in this recording. Nor can this be experienced with headphones, which preclude physical interactions with the space.” In 1999, I dutifully turned up the volume and waited for the physical response - but no music streamed out of my ears. Was the composer putting me on, I thought?

Which brings us to that bundt pan in Teotihuacan, a feature of the second CD Amacher released, Sound Characters (making sonic spaces) (2008). At the time, I believe I did take the bundt pan as confirmation of a put-on. Yet the sounds on this CD were fascinatingly hard to pin down. They are continually in motion in a manner that never reveals a source. The feeling they give me is of an unending, Escher-like construction; a space you enter and either cannot or do not want to exit.

Now, with Amacher’s writings, I understand that a projected space like this is precisely what the composer was after, most seriously and deliberately. “I would like to dream that I could make music that triggered another music in the listener’s mind,” she said in a 2004 interview. “I think to me it’s almost more interesting than the music itself really.”

Listening to: Crickets changing tempo as the temperature drops

Cooking: Dinner for my mom’s 91st birthday