I really enjoy quiet.

I know, from John Cage’s work, that there is no silence. But there is quiet. It’s full of sounds you only hear when it is quiet.

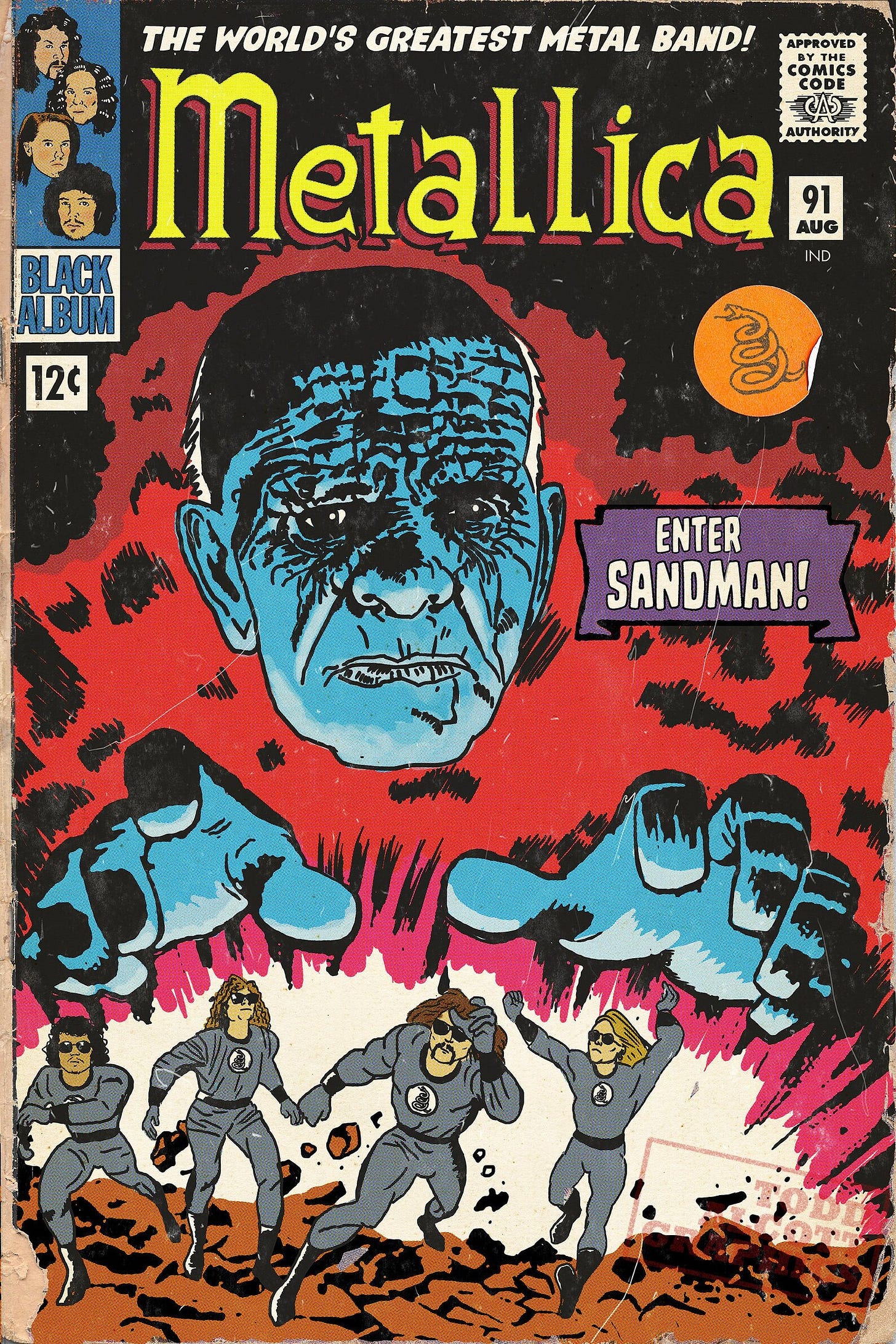

This weekend, my neighborhood was not quiet thanks to a rock festival – Boston Calling. The main stage is about ½ mile from where we live. And the headliners were Nine Inch Nails and Metallica.

When the festival – three days long – finally stopped, quiet rushed in and flooded the town. Moreover, it was a holiday so there was little traffic on the street. And no construction work.

What a balm! I heard the wind. I heard the birds. I heard my neighbor’s adorable little girl shrieking with her little friend. I heard the fan in our refrigerator. I heard every click of this keyboard as I type.

I didn’t listen to any music. (During the festival, I cranked the volume on records to drown out the drum hits and bass tones bleeding from the stage.)

Quiet is very beautiful.

It is also where our own music starts. We record at home - we have since the late-1990s – but have no “soundproofing.” So we wait till the rest of the world is quiet enough not to show up too much behind our instruments and voices.

We wait till the construction workers go home. We wait till the neighbor’s little girl goes to sleep. We wait till most cars stop driving by. We wait till the airplanes from Logan stop flying overhead. It’s now very late at night. And then – after listening hard on open microphones to make sure we haven’t missed any obtrusive small sounds – then, we make noise!

Much of my writing is done this same way; a habit formed long ago. Growing up in a New York City apartment, there wasn’t much privacy and there wasn’t much quiet – until late at night. I waited till everyone else went to sleep, and then I did much of my schoolwork. By the time I went away to college, the habit was ingrained: I stayed up nights reading and writing, not necessarily because I put in extra time, but because I needed the time to be quiet.

Now, these essays you read are also written mostly at night. Late at night. Just like our music.

I was listening to the quiet when an electric car drove by in a hushed cloud of choral voices:

These Honda hybrids are very popular in our neighborhood, so lately we hear choirs passing by often. At first I thought it was music playing on car stereos, muffled by their closed windows… until I realized there was no way all these drivers were listening to Vangelis.

The sound of the Honda hybrid is synthetic, created to replace the engine noise of a traditional car. Which means someone had to make that sound – artists, in other words.

Holly Herndon and Mat Dryhurst are musicians and futurists. This was a commissioned project for them, which (Mat told me on social media, when I asked) took a year but then seemed to go nowhere… until Holly’s father picked them up at the airport one Christmas, driving his new hybrid. Which was playing their tune. (More or less – it’s uncredited, and seems to be unchanging as opposed to the environmentally responsive technology described by their original proposal.)

I was amazed to learn that artists I am familiar with were behind the singing Hondas in our neighborhood, at least in part. But it makes perfect sense, because who else would dream up a sound? It could have been Vangelis after all. Or Eno, who wrote the startup sound for Windows 95. But it’s 2022, so it was Holly Herndon and Mat Dryhurst.

Mat explained to me that they didn’t want to make a “skeuomorphic mechanical sound.” I had to look up skeuomorphic – it’s when old forms are applied to a new technology, like the sound of scrunching up paper when you empty the trash on a Mac, or the icon of the trash can itself. So Holly and Mat started from scratch, rather than from the vroom vroom we associate with traditional cars.

Mat and Holly’s reasoning, research and vision are impressive – and I am a fan of Holly’s records, which always transcend their technology for me and are simply a pleasure to hear regardless of how much I know about what went into them.

But outside my window, the effect of this Honda hybrid singing is a little too close to the bleed from Metallica’s festival set. Perhaps if their full vision had been realized – and it could be one day – so that these cars were responding to my street, to our town, to what is in front of them that needs warning and what is around them emitting sounds including other cars… As it stands, there is simply a lot of this identical electronic choir sound shuttling around our neighborhood. Making it less quiet.

The time will come when we have to scrap a take because a singing Honda drove by at night, while our own mics were on. There are, in fact, passing planes and traditional cars buried in all our recordings, despite best efforts to exclude them. But I think the Honda sound would be harder to hide in a mix, precisely because it is not mechanical. It is the work of another artist, and seems like it would demand treatment as such. We might respond to it – we might work in dialogue with it – but I don’t think we could just blend it in the environmental background and expect the listener not to notice. It commands attention, as the work of an artist usually does.

Which is exactly why I think I couldn’t ignore the sounds from Boston Calling. On a DB meter (and yes, I checked), they weren’t that loud (undoubtedly, the festival was using DB meters too and keeping them within certain limits). Yet I could not shut them out. There was too much intention in them.

I wonder if instead of a new sound for electric cars, we might dream up a future where our cities are so quiet that even the smallest mechanical sounds they make – tires on pavement, air disturbed by motion – are enough for us to hear their approach. Like it might have been today, on our town’s holiday from noise.

Listening to: The Gleam, by Park Jiha

Cooking: Vietnamese coffee prepared by a friend

I write about electric cars for a day job. This post might get a reference in a new article if I'm lucky and the pitch gets accepted.

Your ideas are intriguing to me, and I wish to subscribe to your newsletter. Actually I just did.