Flooding the Zone

Spotify's Firehose

Spotify’s mission statement is ludicrous, but there it is right on their website:

“Our mission is to unlock the potential of human creativity - by giving a million creative artists the opportunity to live off their art and billions of fans the opportunity to enjoy and be inspired by it.”

This week, the company gave the lie to its mission in a fresh new way by declaring, “We estimate that there are around 200,000 professional or professionally aspiring recording acts globally.” Which means they won’t rest until they not only provide the means of support to all 200,000 of those professional recording artists, but another 800,000… who couldn’t be professionals according to Spotify, but what else would they be if they managed to live off their art?

The illogic of these statements might be chalked up to casual corporate bullshit. But Spotify doesn’t say them in passing and hope they disappear quickly – they craft them to post on overdesigned websites announced with PR campaigns. And then they throw around jumbles of statistics to make them seem grounded in fact. Here’s how they explain the 200,000 professional musicians figure: On Spotify, “There are 165,000 artists who have released at least ten songs all-time (meaning they have a body of work to earn from) and average at least 10,000 monthly listeners (meaning they have been able to attract the beginning of an audience).”

That seemingly arbitrary cut-off (ten songs and 10,000 monthly listeners) doesn’t actually get us all the way to 200,000 – but wait…

“We also see this through our integrations with Songkick, Ticketmaster, and dozens of other live and virtual ticketing partners: 199,000 artists had any gig, live concert event, or virtual event listed at some point during 2019 (the last full year not impacted by pandemic cancellations), demonstrating professional activity outside streaming.”

So 199,000 artists are listed online as playing live gigs – which has nothing to do with streaming, or recorded music at all, but whatever – and that seems to give us the 200,000 figure. Kind of. Because maybe it’s worth pointing out that not every recording artist with 10 songs and 10,000 monthly listeners also played a live gig in 2019? Like the Beatles, for example… or Miles Davis… or anyone else who has ever died, and/or didn’t happen to post a 2019 gig on Songkick or Ticketmaster…

Ridiculous reasoning aside, why is Spotify so eager to torture figures in order to get to this particular total of 200,000 professional musicians (especially if their mission is to support 1,000,000 of them)… Might it be just so they can say the following:

“Based on these estimates, more than a quarter of these professionally aspiring artists generated more than $10,000 in payouts from Spotify alone last year (suggesting more than $40,000 in total recorded revenue, and more when you consider touring, merch, and other business lines).”

Which makes… no sense also. But let’s puzzle it out. A quarter of 200,000 = 50,000 “professionally aspiring” artists making $10,000 gross revenue from Spotify in 2021. Couldn’t they just say that?

Actually, they did – there’s even a slide of it at the top of their “Loud & Clear” website - and what’s more, this one is likely based on real figures. But I guess the gap between 52,600 rights holders grossing $10k annually, and their mission of “giving a million creative artists the opportunity to live off their art” was just too, too great to put out there without a smokescreen.

Talk about blowing smoke: let’s remember that Spotify’s boast here is about $10k annual gross for artists, in 2021 dollars. Not for any given release, but for rights holders’ entire catalogues. And not from any platform, but the one that hogs roughly the same percentage of streaming that Amazon does of online retail. Regardless of what Spotify asserts (without documentation) about “total recorded revenue” magically quadrupling their $10k contribution to $40k, they are by far the single largest platform and streaming is (according to the RIAA) 83% of all recorded music revenue in the US.

In other words, $10k a year from Spotify is not enough to support any musician, much less 52,600 of them. Or 1,000,000 of them.

Not that someone isn’t making substantial income from Spotify – they did, after all, pay $7 billion to rights holders in 2021. But here’s how they choose to tell us where that money went, in descending order of average annual royalties:

500 “Chart Topper Artists” (The top 500 of all artists by listener numbers). Average Royalties Generated in 2021: $4 million

2,700 “Heritage Artists” (More than 500,000 monthly listeners in 2021 and 80% of streams from tracks more than 5 years old). Average Royalties Generated in 2021: $473,000

26,900 “Established Artists” (In the top 50,000 artists by listener numbers for three years running). Average Royalties Generated in 2021: $218,000

21,600 “Breakthrough Artists” (Fewer than 1 million streams prior to 2020 - and are now in the top 50,000 of all artists by streams). Average Royalties Generated in 2021: $90,000

4,900 “Specialist Artists” (More than 25,000 monthly listeners with over 90% of tracks classified in Children’s, Classical, Easy Listening, Holiday, Religious, or Soundtrack). Average Royalties Generated in 2021: $36,100

27,400 “Market Mover Artists” (More than 25,000 monthly listeners and from one of the 17 markets - Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Greece, Italy, Mexico, Middle East & North Africa, Philippines, Poland, Russia, Thailand, Turkey, Sub-Saharan Africa excluding South Africa, Venezuela, and Vietnam - where recorded music grew more than 25% in 2021). Average Royalties Generated in 2021: $24,800

72,700 “DIY Artists” (More than 10,000 monthly listeners and they distribute music to Spotify via an artist distributor). Average Royalties Generated in 2021: $15,100

Got that? Of course you don’t. Seven more or less random categories, each defined by arbitrary rules much like those that delivered the calculation of 200,000 global professional musicians. But again, let’s puzzle this out…

Summing the number of artists listed in these seven categories, we get a total of 156,700. Not exactly the same as the 165,000 “artists who have released at least ten songs all-time and average at least 10,000 monthly listeners,” but close. (Asking Spotify to be precise with numbers seems to be unrealistic.) Close enough that perhaps it’s a fair assumption these two figures are related - and the seven categories are subdivisions of the 165,000 total “professional” accounts.

But something goes kerflooey when you try and add up the dollar amounts. Multiplying average annual income by the number of artists in each category, the total paid to these 156,700 accounts would be more than $13 billion in 2021… or almost double what Spotify said they paid to all rights holders.

Back to the drawing board! Maybe these seven categories are not distinct, but overlap? Might there be DIY Market Movers who are Specialty Artists Breaking Through, on their way to joining the ranks of Established or even Heritage DIY Market Mover Specialty Artists? Hmm…

It seems all we can take away from these muddled figures are… muddled figures. Whatever the breakdowns are supposed to tell us about artist income, they don’t.

But something they do tell us is maybe even more interesting.

Let’s go back to the total number of artists in these categories - 156,700 - or nearly all the 165,000 “professionals” on the platform as identified by Spotify. Put this up against another factoid Spotify includes in their report:

“Of the eight million people who have uploaded any music to Spotify…”

8 million?

That leaves 7,843,300 who don’t fall into any of these seven categories, 7,835,000 of whom Spotify doesn’t even consider “professional.”

In other words, nearly every account on the platform is excluded from all of the confusing accounting above.

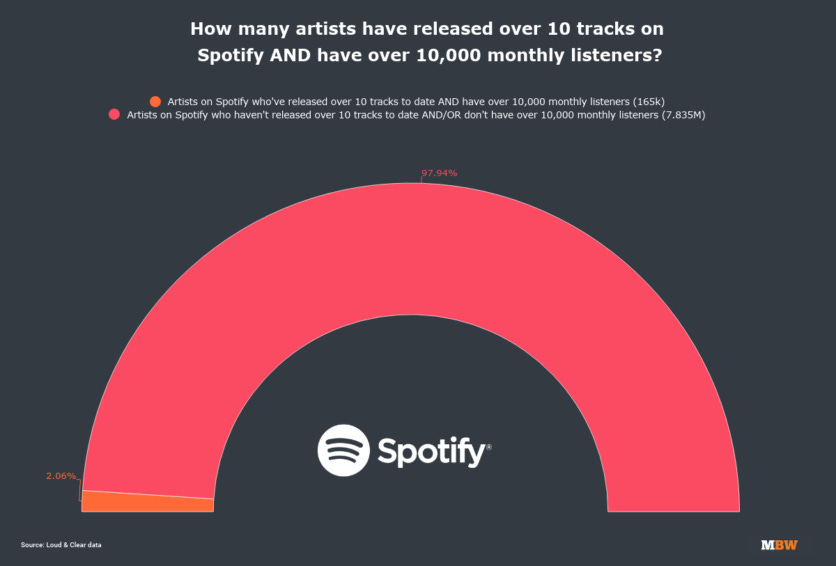

Tim Ingham of Music Business Worldwide called attention to this surprising detail and even made some handy slides to illustrate it. Here is a graph from MBW illustrating the ratio of “professional” accounts to total accounts on Spotify – the professionals are the tiny slice of orange:

And here – to me this is even more remarkable – is a chart eliminating the question of audience and income altogether, simply dividing between accounts that have released enough music for an album and those that haven’t:

Album artists are less than a third of everyone with work on Spotify.

So never mind the financial shenanigans, which Spotify chooses to discuss in the most mystifying ways possible. What Spotify is concretely telling us, amid the blizzard of randomly defined categories and figures that don’t add up, is that the bulk of artists on the platform are probably not who we thought they were. 98% are not professionals, at least as defined by Spotify. And 67.5% don’t make albums at all.

No wonder Spotify doesn’t seem to care what professional musicians think about the platform.

I’m reminded of the situation for journalists on Facebook.

Facebook may dominate the distribution of news. But professional news sources don’t dominate Facebook, “non-professionals” do. Which is precisely how disinformation campaigns are able to use Facebook for their own ends.

Recent political and now military crises have given us all a crash course in this version of propaganda. “Flooding the zone with shit” is a strategy identified with Steve Bannon, who framed it just like that in a 2018 interview with Michael Lewis. But it is based on a model developed in Putin-era Russia, dubbed “Firehose of Falsehood” by a 2016 Rand Corporation white paper. The paper describes how this disinformation strategy is tied specifically to digital media: it is “high volume,” “continuous” and “repetitive” in ways that only online communication can facilitate. In the old days, the Soviet Union could block analog signals to control the information environment: by jamming radio and TV, or confiscating printed journals and books. In the digital world, where information flows more easily around blocks thrown in its path, Russian propogandists instead developed a technique of disinformation through sheer volume. You can dilute whatever you don’t want listened to by drowning it in a sea of… anything and everything. You just have to make sure there’s a lot of it.

I’m not saying that Spotify is deliberately creating Bannon/Putin-style disinformation campaigns, and more importantly the stakes in music are obviously much, much, much lower than in news media. But what Spotify’s latest statistics reveal is that the streaming platform’s environment resembles a firehose model of information more than a gatekeeper one. Before streaming, much of recorded music was vetted by labels, journalists, radio and retail. As part of their current PR campaign, Spotify brags that they have dispensed with these old “barriers to entry,” claiming they are thereby “democratizing” audio:

“Streaming has fundamentally changed the music ecosystem - lowering barriers to entry and democratizing access to audio for listeners across the world. Artists no longer need big budgets to create, distribute, and amplify their music around the world.”

But is volume of information the same as democratization of it? What we’ve all experienced on social media platforms – Facebook, Twitter, and the like – is that an unrestrained amount of information can actually threaten democratic processes, increasing top-down control rather than challenging it. Indeed, as is obvious in Bannon and Putin’s cases, turning up the flow of content can be part of a deliberate attack on democracy and pluralism.

Again, I want to emphasize that I am not equating the import of flooding the zone in music with flooding the zone in news. However, it’s possible that the fundamental goal is the same: control. It seems intuitive that eliminating traditional gatekeeping would be automatically democratizing. But do we really need any more evidence that it’s not?

Spotify’s boast about lowering barriers to entry is, of course, accompanied by more confusing statistics. “Across 2020 and 2021, over 150,000 artists were added to Spotify playlists for the first time,” they say. But this is offered without any explanation for how 150,000 artists could be newly discovered, when there are only 165,000 professional artists on the platform.

Or might it be that a substantial number of these 150,000 newly playlisted artists are actually drawn from the 98% of “non-professionals” on the site…?

Spotify doesn’t share data they don’t want publicized, but journalists have uncovered a key set of artists who might qualify as non-professional (fewer than 10 tracks released under their name), yet generate huge numbers of streams from playlists: the so-called “fake” accounts created to mask tracks commissioned by Spotify themselves. This is a scandal that now dates back a number of years, but was just this week confirmed again in fresh investigations by two Swedish newspapers. “The Swedish fake artists who took over on Spotify - bigger than Robyn,” runs the headline in Dagens Nyheter. Meanwhile, Svenska Dagbladet went deep on one example: “Christer Sandelin has not had a hit in his own name for years. But in the shadows, he has built up a million-dollar industry on Spotify. Here's the story of how chill music took over your playlist.”

Before chill music can take over your playlist, the playlist has to take over your listening. And that part of the story is, I believe, the same as how Spotify “democratized” access to music. The firehose of streaming is impossible to manage as a listener: 8 million artists is the kind of high volume chaos that propagandists count on to destabilize information. How else are we to deal with this onslaught but to throw up our hands and then passively accept algorithmic recommendations, playlists, a manageable subset of information supposedly tailored to our individual desires. We need that guidance in the face of 8 million artists more than we ever did from the gatekeepers of analog media, which was by comparison very limited.

With its 98% “non-professional” artists, Spotify has flooded the zone.

And then they tell us it’s our fault – professional musicians’ fault – that we’re drowning.

Listening to: One album at a time

Cooking: Mangoes and papaya, while we wait for local produce to emerge from the cold muddy ground

The disconnect between the promise of what they sell and what we get is so disappointing - I wrote about how unfriendly algorithms are to small indie artists here: https://locarmen.substack.com/p/algorithms-are-not-your-friend?s=w

Great! This one should be framed and on a wall somewhere.