Marvin Gaye’s music has played a role in two recent high-profile copyright lawsuits, though with opposite results – in 2015, Robin Thicke and Pharrell Williams were found guilty of plagiarizing Gaye’s “Got to Give It Up” for their hit “Blurred Lines,” and ordered to pay millions of their royalties in damages. But last month, Ed Sheeran was found innocent of similarly plagiarizing Gaye’s “Let’s Get It On,” and will continue to hoard all profits from his pale-as-milk imitation “Thinking Out Loud.”

Generally, the music industry was horrified at the punitive decision against “Blurred Lines” in 2015, and applauded this recent acquittal as establishing an acceptable norm. “The Ed Sheeran lawsuit is a threat to Western Civilization,” ran the headline to a Washington Post op-ed about the case, and it was not alone in its hyperbole. The fear the case inspired in rightsholders centers around the idea of copyrighting common elements to music. “Much like math or writing, music is limitless in its possibilities but paradoxically required to repeat itself. The notion of copywriting [sic] any chord progression, let alone one as common as the one used in ‘Let’s Get It On,’ makes no more sense than copywriting [sic] the numbers six and 13 or the conjunctions ‘and’ or ‘but,’” as the Post op-ed put it.

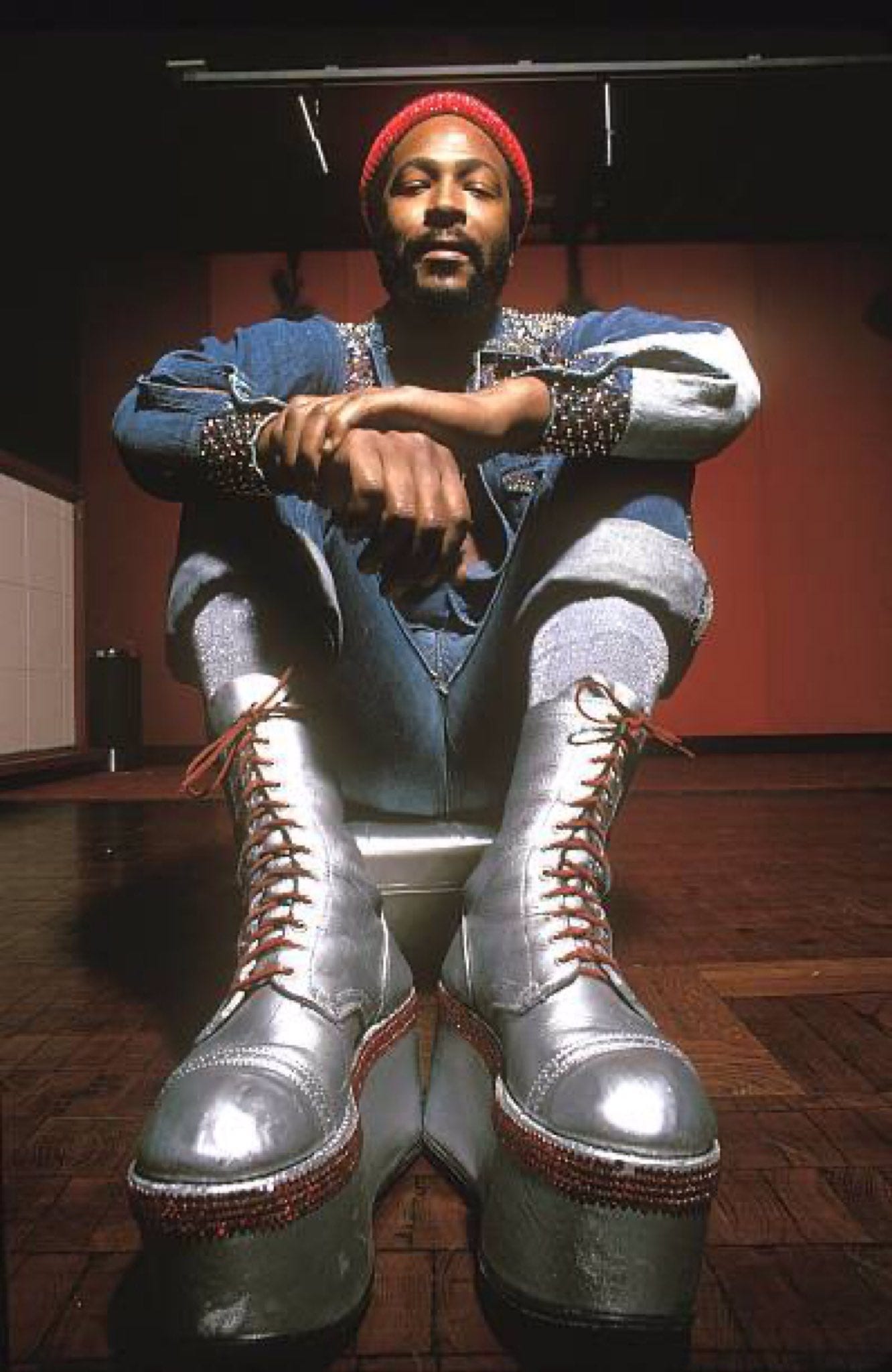

But the groove that “Let’s Get It On” inhabits so beautifully is not math, nor do its lyrics lean on atomistic bits of language like “and” or “but.” No one has to be an expert in musicology or any other field of learning to know that Marvin Gaye’s song is unique. Just listen to it:

And now listen to this back-to-back comparison of “Let’s Get It On” with the Ed Sheeran song under question, spliced together by musician Rick Beato:

Regardless of the merits of the legal case that was brought against “Thinking Out Loud,” who are we kidding? The Sheeran song is a rip-off of the groove from “Let’s Get It On” – a bloodless, pointless one in my opinion, but a rip-off for sure. The four-chord sequence of the verse is directly lifted from the Marvin Gaye song both harmonically and rhythmically, with only a single note difference in voicing (Sheeran uses D/F# in place of “Let’s Get It On”’s F#m, leaving a stray C# as the one thing he neglected to copy). “It’s way closer than ‘Blurred Lines’ was to ‘Got to Give It Up,” concludes Rick Beato, as he walks viewers through both tunes on a guitar. If you needed further evidence, Sheeran himself has moved effortlessly between the two songs in concert (documented by a fan video now removed from YouTube but which was shown in court).

“Blurred Lines” is, similarly, a rip-off of the groove from “Got to Give It Up” – and the artists again betrayed their influence in statements they themselves made about the similarity. In both cases, the latter-day songwriters utilized a totally normal and accepted aspect of creation: imitation of what’s gone before.

So why all the sturm und drang?

If neither song were a hit, generating millions in profits, there would be no lawsuits and no such “test cases” for copyright. Like all the rest of us copping riffs or grooves or harmonic twists or an interesting bridge from a song we admire, these artists would continue to create new work that leans on old in some ways, and in other ways doesn’t. That’s just making stuff.

It's the extreme amount of money involved that triggered these suits, and it’s the letter of the copyright law that they appealed to. Although the cases were very similar, one went one way, one the other. That’s not precedent, it’s chance. Even the lawyer who represented Robin Thicke and Pharrell Williams was hard pressed to say what was significantly different about the Sheeran case, other than the personalities. “I don’t need to dredge up old news,” Howard King said to Variety, “but this is a problem I had with the ‘Blurred Lines’ case: My artists were not as involved or as engaged as Ed Sheeran was.”

In other words, Sheeran effectively sold the jury a story, while Thicke and Williams did not.

But what was that story?

“Sheeran told the court that he preferred to work quickly, with most of his songs written in a day, or even a matter of minutes. He said he had written up to eight or nine songs in a single day in the past,” reported the Guardian. “Most pop songs can fit over most pop songs,” he testified. “You could go from ‘Let it Be’ to ‘No Woman, No Cry’ and switch back.” What’s more, “Sheeran said that after recording ‘Thinking Out Loud,’ he thought ‘it sounded like it emulated Van Morrison, production-wise,’ and cited other songs by Morrison – who he has since befriended – with similar chord sequences.”

According to Sheeran, pop songs are written in a matter of minutes and are all more or less alike – plagiarism being therefore unavoidable - and this particular one was in fact lifted primarily from Van Morrison not Marvin Gaye. So yes, plagiarized, but not guilty as charged cause the wrong person brought the suit. And Van the Man, anti-vaxxer and raging paranoiac? He’s a friend so he wouldn’t do such a thing. Anyway he’s got other legal problems to worry about.

Apparently, this story worked. After the verdict Sheeran continued to lean on it, elaborating even further. “There’s four chords that get used in pop songs, and there’s however many notes – eight notes or whatever,” he said to CBS Sunday Morning, dismissing most keys and 1/3 of the octave. “And there’s 60,000 songs released every single day,” he continued, emphasizing his quantity over quality argument. I mean, if you’re writing a song every few minutes, who can bother to use more than the same four chords anyway?

This is the story that the music industry is celebrating with Sheeran’s legal victory. Songs are trash, essentially. Why are you bothering to analyze them at all?

As far as Sheeran’s work is concerned, I imagine he is being frank. His songs are hackwork. I believe he may not yet have used every note in the octave, even though Louis Armstrong seemed to need them all for just the intro to a single tune in 1928.

Sheeran’s story of music doesn’t help us understand Louis Armstrong, or Marvin Gaye for that matter, but it is strikingly suited to our current and upcoming technological moment of creation by Artificial Intelligence. All songs can be made in a matter of minutes, because they are all alike. Feed in the four chords and eight notes that dominate pop hits, and out pop more hits – eight or nine a day, or even 60,000. Why not? None is unique.

At least, not unique enough to form the basis of a successful copyright lawsuit. Which means the corporate owners of AI-generated material, even if based on specific prior songs and artists, are heading for vast unshared wealth.

Much of the music industry is celebrating Sheeran’s acquittal as a victory for songwriters and publishers. Perhaps, in an older paradigm, that would be true. But in our current technological moment, the story Sheeran told to justify his exclusive hold on this intellectual property has different implications. As a songwriter, he is proto-AI: a blender of cliché. He is indiscriminate, prolific, fast, bland and very, very rich.

“Thinking Out Loud” was the fifth most-streamed song of the 2010s on Spotify; Sheeran’s “Shape of You” (for which he was also sued for plagiarism) was number one. His music is, evidently, perfectly suited to the medium. And AI is perfectly suited to make his type of music - without any intellectual property rights involved at all. If this was a victory for songwriters, it was a Pyrrhic one.

Listening to: Jerusalem, by Emahoy Tsege Mariam Gebru

Cooking: Peanut-butter crackers in the tour van

Hey Damon. This is Jason. I met you and Naomi in Philly a few nights ago.

I recently wrapped up a music entrepreneurship class. Your newsletters often cover topics we are discussing in class. The professor frequently invited the class to share news or any topics we would like to discuss. Your newsletters often became the basis of a class discussion. I thought you may enjoy knowing that.

We were discussing this Sheeran thing in out last class which was a week or two ago.

This is the most detailed discussion I've seen on this particular case (thanks to commenters as well!) --- and on songwriting "originality" in general. You could go back to George Harrison's "My Sweet Lord" in which the plagiarism was unconscious but, I think, George copped to it, saying, essentially:"Yeah, it's the same song." (At least as I remember it -- don't quote me!) And I remember the old saw: "Every blues song is stolen from every other blues song." But that goes back to the blues as true folk music, with no "author," and "floating verses" that showed up all over the place. In this case you're getting into more subtle questions of authorship. Think of all the jazz "compositions" based on the chord changes of popular standards, but considered original compositions because the original melody is never even alluded to, never mind the rhythmic patterns-- thank you, Charlie Parker! And then in the rock world, you've got Leon Russell, revealed in Bill Janovitz's new biography as so deeply insecure that he didn't consider "This Masquerade" original -- or at least original ENOUGH, because the chord changes came from the Matt Dennis standard "Angel Eyes." According to Janovitz, Russell thought that's why the song appealed to a jazz player liked George Benson, not because of any unique qualities of its own. I'll leave to to folks here to argue whether Russell was maybe a bit too self-critical. But it does leave open the question of how we determine something to be original. I think Damon would have made a good witness for the plaintiff here!