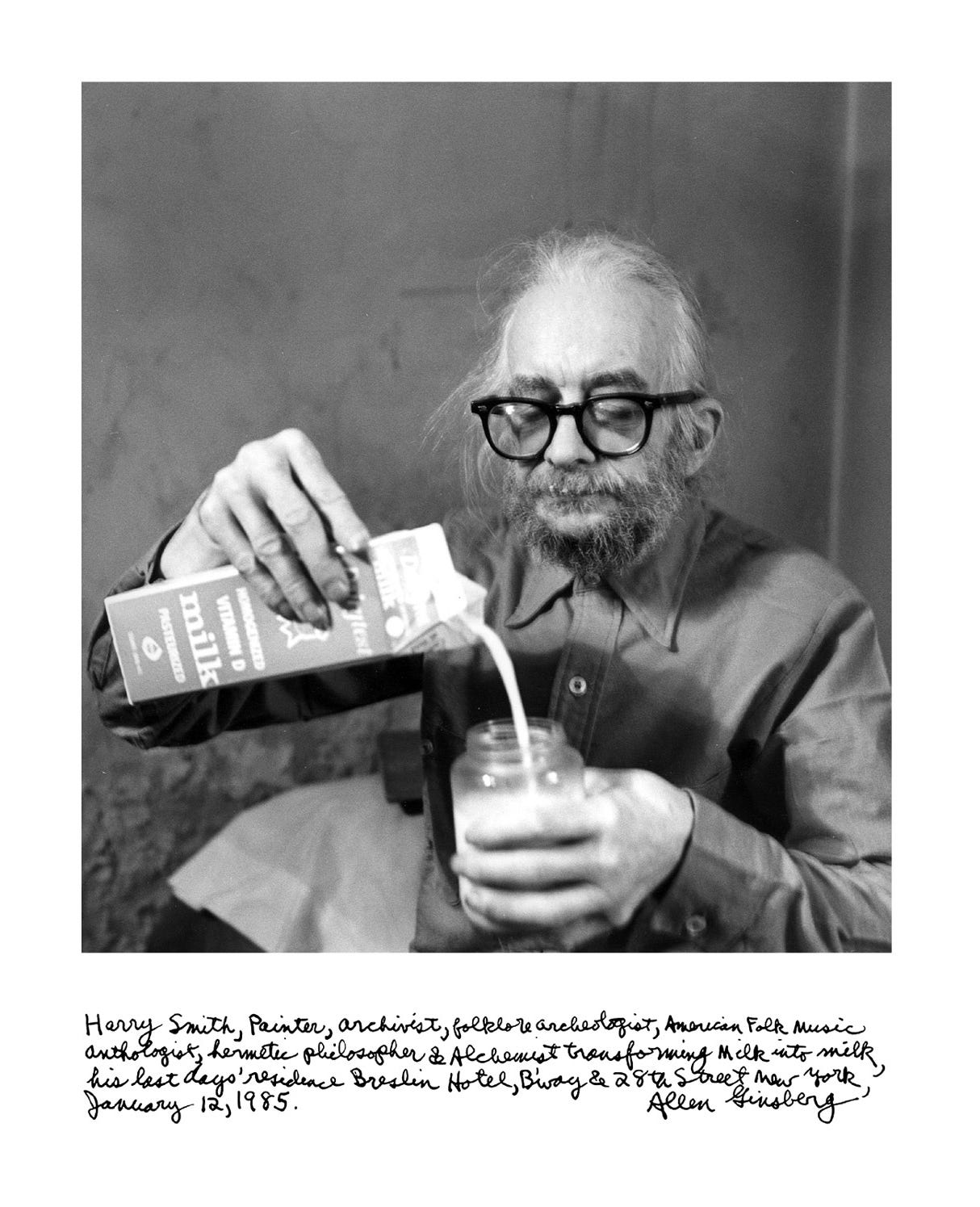

Harry Smith

Materials for the Study of the Religion and Culture of the Lower East Side

For those of us who mediate the world through records, Harry Smith is editor of the Anthology of American Folk Music released by Folkways in 1952 – that now-iconic but no less bizarre 6-LP collection of commercial 78s made “between 1927, when electronic recording made possible accurate music reproduction, and 1932 when the Depression halted folk music sales.” “The Old, Weird America” Greil Marcus famously called the world the Anthology conjured up. And according to many who were there at the time, the folk revival of the 1950s and 60s wouldn’t or couldn’t have happened without it. “I'd match the Anthology up against any other single compendium of important information ever assembled. Dead Sea Scrolls? Nah. I'll take the Anthology,” wrote John Fahey in 1997, when it was reissued on CD by no less than the Smithsonian.

Yet as part of a survey of Harry Smith’s life and work – there are two right now, the museum exhibition “Fragments of a Faith Forgotten,” and the new biography Cosmic Scholar - the Anthology is not only just one work among many, but just one collection among the many and often even more bizarre collections Smith assembled. There were the bandages with bloodstains from tattoos; paper airplanes found in the streets of New York; string figures; Ukrainian Easter eggs; Seminole patchwork samples… not to mention, as his one-time assistant and now archivist Rani Singh adds,

“… pop-up books, audio recordings, Indian women’s beaded costumes, tarot cards, and gourds… things shaped like other things (spoons shaped like ducks, banks shaped like apples, anything shaped like a hamburger)…”

The 78s Smith inscribed into our music history were but one pile in a series of crowded and often squalid living spaces from which he would invariably be evicted. Libraries of esoteric knowledge were assembled and lost this way by Smith – even his own artwork was lost this way, paintings and films that represented years of labor. The Anthology records were a flash in a continual blur of material culture Smith gathered around him and then let go again. They also weren’t the only music Smith was engaged with - as his biography attests, he was deeply connected to bebop jazz recordings and jazz musicians in the 1940s and 50s, listened obsessively to Beatles and Dylan records like everyone else in the 1960s, and toward the end of his life was regularly attending midnight screenings of reggae films The Harder They Come and Rockers, urging people to listen to Donna Summer, and going to all-ages hardcore shows in New York.

Smith’s role as folk music anthologist was also not his only public success - his animated films were celebrated in avant-garde circles much as the Anthology was among folk revivalists, and it’s the films that largely populate the museum exhibition mounted by the Whitney earlier this year, currently installed at the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts at Harvard University. The exhibition, if you get the chance to see it, is a wonderful dive into Harry Smith’s visual esthetic – though an uncharacteristically spare one. There are carefully presented examples of his drawings and paintings, sometimes as projected slides of lost physical works. There are a few tastefully framed samples from his collections – a handful of string figures, a couple of 78s (on loan from Greil Marcus!). There are a few of his commercially reproduced works like the cover of the Anthology, which looks a bit uncomfortable hanging on a wall, and 3-D greeting cards he designed for sale which do not exactly work in 3-D despite the provided viewing glasses.

And then there are the films - digital copies projected in loops as exhibitions do or, if you are very lucky, screened from actual prints in accompanying theatrical programs. But even these rare screenings of the original films are more neatly presented than the artist himself would have done. Harry Smith often performed alongside his films, as it were, adding soundtracks on records or colored gels in front of the projector. The announcement for the 1980 premiere of his late multi-screen masterwork, Mahagonny (or Film No. 18, set to the Weill/Brecht opera), at Jonas Mekas’s Anthology Film Archives, promised “a ‘live’ presentation with Smith restructuring the film at each performance. No two screenings will be absolutely identical… more of an event than a film.”

The performative aspect of Smith’s film screenings was intensified by the artist’s unpredictable behaviors. Here is Smith’s biographer’s account of that first run of Mahagonny, which was scheduled to take place ten times over two weeks:

“In the projection booth, there were four Elmo 16 CL 16mm projectors with gels attached to them to change the films’ color, and hand-painted glass slides… so that on-screen images would appear framed in Moorish or Greek borders, baroque theater prosceniums, or comedy and tragedy masks. Two projectionists handled twelve twenty-minute rolls of film, and Harry operated a tape recording of the opera records and a spotlight with red, green, and yellow filters. He was in the booth at all times, following his notes but making changes nightly…

“Stories about Harry’s presentations on different nights quickly became local legends. Depending on his mood or drug intake, they said, he played tricks on the audience, set off fireworks in the theater, or verbally insulted the audience. As Mekas put it, he was ‘very temperamental’… Dr. Gross [‘a psychiatrist with whom Harry had an uneasy medical and nonmedical relationship’] came on opening night and other nights, but after an argument the day before the sixth performance, Harry told him to stay away. At the next screening, Harry, again high on amphetamines, began shouting at the projectionists and throwing things… As the films started, Dr. Gross walked into the theater, and when Harry saw him, he stopped the projectors, ran into the audience, grabbed Gross, shoved him out the door, then returned to grab the painted glass slides and threw them into the street. The film series could have been continued as planned, since most of the broken slides were not being used, but Mekas canceled the remaining four screenings.”

In the Whitney installation of “Fragments of a Faith Forgotten,” Mahagonny played on a loop in the gallery together with its soundtrack. I found the film very beautiful, as shots of Smith’s New York City and his New York City friends mesmerizingly mix with symbolic still lifes. But of course each time I returned to it, it was necessarily the same.

The curators of the Smith exhibition did manage to include some of the chaos of Smith’s life and work, despite the strictures of gallery presentation. At the Whitney, there was a bright, largely empty area with a view of the Hudson river adjacent to the darkened rooms of objects and film loops. Here the curators placed information about the Anthology of American Folk Music, with its tracks predictably playing on headphones, but more surprising were two large unmarked binders of scanned or xeroxed papers left on tables. These binders, one gathered by the Harry Smith Archive’s Rani Singh, the other by sculptor Carol Bove together with Berkeley bookseller Philip Smith, were a wonderful mess of articles, images, documents, and ephemera relating to Smith and his enthusiasms. Flipping through them felt the closest a museum viewer might come to encountering the piles of material Smith actually lived with and worked on. Or even to the chaotic original screenings of his films.

In the Carpenter Center installation, a third group of binders has been added with seemingly countless scans of covers and copyright pages from Smith’s esoteric library (or at least the version of that library he had at the end of his life). There are so many of these binders they form actual piles in the gallery, left stacked on several benches in a hallway. Even after return visits, it feels impossible to take them all in.

Sitting with the mess of these binders at the exhibitions – and reading about the mess of Smith’s life in his biography – gave me a new view of the Anthology itself. What had always seemed like a vast storehouse of music on those six LPs suddenly felt abbreviated. Smith’s selection of 84 tracks - that mysterious, much debated selection so many have pondered since – is closer in spirit to the relative handful of images that the exhibition curators carefully framed and presented on their darkened gallery walls, than to Smith’s sprawling work as a whole. No wonder Smith included a plan for even more volumes in his original notes to the Anthology – volumes that never did come together, but existed in potential amidst his endless collections.

On the website for the Harry Smith Archive, there is a hint of what Smith’s fuller encounter with recorded sound might be like, freed from the format of mere LPs:

“His last formal project was a series of audio recordings started in the East Village, New York City and continued in Boulder entitled ‘Materials for the Study of Religion and Culture of the Lower East Side’ or ‘Movies for Blind People.’ This collection consists of cassette tape recordings made on a Sony Pro Walkman with sounds of Haitian Street Fairs; Hispanic celebrations; local churches; children’s jump rope rhymes; folk and rock music on the street and in local clubs; Bowery bums coughing and praying on their deathbeds; Gregory Corso; Allen Ginsberg; the noises of Tompkins Square Park; cows at sunset and more, recorded during the 1980s.”

The biography Cosmic Scholar quotes Smith’s friend and sometime protector Allen Ginsberg about these recordings:

“He put the microphone out the window, wrapped in a towel, and just sucked in all the sounds of the city for miles around with that microphone. Sort of like Cageian music. And it climaxed on July 4th when you get all the fireworks. That’s mostly what he was doing. He did it hour after hour, day after day.”

And the book cites Peter O. Whitmer, who met Smith while visiting Ginsberg, for these indirect quotations about the recordings from Smith himself:

“What I do… is take all the sounds and speed them up so I can edit them. I have found surges in sound, punctuated by a single bird call or dog bark, that are pure beauty. These surges – these waves of energy – are really fascinating. So far I have recorded two full moons and a summer solstice – about one hundred hours in all.”

Whitmer asked Smith how best to listen to these recordings.

“I’d say with heroin, that’s probably the best. After all, it is one hundred twenty hours.”

Listening to: the Northern Lights

Cooking: pumpkin kibbeh

In a way, his work reminds me of the sound archivist Tony Schwartz, who was as eccentric as Harry in his own way. Tony suffered a form of agoraphobia where he never left his New York neighborhood, but he recorded all sorts of things like the street musicians and ethnic festivals. He was among the first who recorded Moondog, the bearded blind street musician who famously wore a Viking helmet and performed on homemade instruments. He also collected home recordings of people around the world who would send tapes to him. Worth looking into: https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tony_Schwartz_(sound_archivist)#

I may be misremembering this but didn't R. Crumb draw Harry Smith and devote a comic to him?