Isolation Row

Scott Walker's Climate Of Hunter

This essay was written for a collective album-by-album account of Scott Walker’s discography, edited by Rob Young. The first album of Scott’s “third phase,” as Rob calls it in his introduction, fell to me: Climate of Hunter. I love all of Scott Walker’s work, though I certainly listen most frequently to the wonderfully orchestrated solo albums of his “second phase,” in particular Scott 4. (Naomi and I covered one of the songs on that masterpiece for the soundtrack of a film about Scott Walker.) But the “late” work - which I would count from Scott’s contributions to the last Walker Brothers album Nite Flights, through the end of his life - are for me an endlessly intriguing, increasingly difficult, always rewarding puzzle. I took the assignment as a challenge, really, to try and understand better how these mysterious albums function, which led me to a close reading of lyrics.

Originally published in No Regrets: Writings on Scott Walker, ed. Rob Young (The Wire/Orion Books, 2012).

And now, what’s going to happen to us without barbarians?

They were, those people, a kind of solution.

- From CP Cavafy, ‘Waiting For The Barbarians’ (1904)[i]

If the first four tracks on the final Walker Brothers album, Nite Flights (1978), announced the rebirth of Scott the songwriter, Climate Of Hunter (1984) was the even longer-awaited return of Scott the auteur. Only the second album containing all original songs in his career, it is the true follow-up to 1969’s Scott 4. But what a difference those fifteen years make. In a retrospective interview filmed for the documentary 30 Century Man, Walker speculates that had he not taken a detour after Scott 4, he would have arrived at the same place, just ‘sooner – I would have been there a lot sooner.’[ii] Could a much younger man have made Climate Of Hunter, however? Not because of its darkness, so present in Walker’s youthful work as well. But there’s an abstraction to Climate Of Hunter – and to all of Walker’s subsequent albums – that is missing from his earlier records, or was perhaps inaccessible to the artist at that time. Walker’s work from Climate Of Hunter onwards would seem to exemplify Edward Said’s description of ‘late style’: ‘There is an insistence in late style not on mere ageing, but on an increasing sense of apartness and exile and anachronism,’ which leads not toward a greater ‘harmony and resolution, but... intransigence, difficulty and contradiction.’[iii] The ‘difficulty’ of these later works of Walker’s, so often remarked on, is in this view not a resolute thumbing of the nose at the audience, or record company executives, or any other aspect of the pop music life. It is, on the contrary, art made of irresolution. If Scott Walker had alternately embraced and shunned the role of pop star from his UK debut through the second, definitive end of The Walker Brothers, in Climate Of Hunter he sidesteps that issue altogether. No longer waiting for the barbarians in the form of the dreaded, yet hoped-for, mass response, he embarks instead on a practice in which, as Said puts it, the artist treats his or her work ‘as an occasion to stir up more anxiety, tamper irrevocably with the possibility of closure, leave the audience more perplexed and unsettled than before.’ No wonder, then, that these late albums haven’t followed one another quickly, or fallen into any kind of linear progression, à la Scott 1, 2, 3... On the contrary, in Said’s words, this ‘type of lateness... is a sort of deliberately unproductive productiveness, a going against.’[iv]

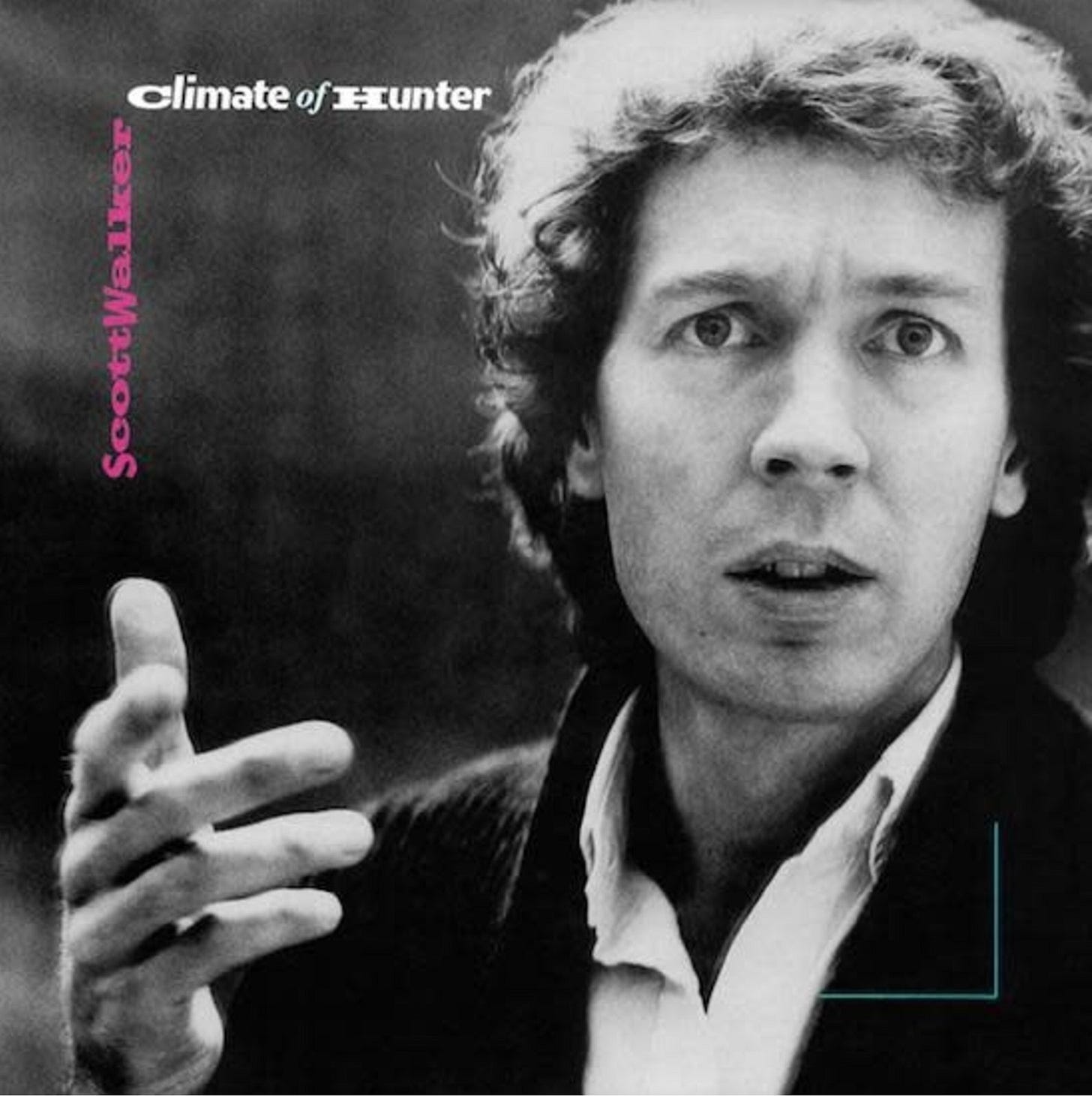

Which is not to say that these albums are merely hermetic. The abstraction of Climate Of Hunter has at times led to its critical dismissal, and certainly contributed to its failure as a commodity for Virgin Records. But as a work of art, its openendedness would seem to undercut the simplified teleology of ‘success’ or ‘failure’ of communication with its listeners. Climate Of Hunter addresses us quite directly as an audience – even Walker’s gaze on the cover, meeting our eye, with mouth open and one hand pointing at us as if in the middle of a remark, asks us to listen. And the album’s first line – ‘This is how you disappear’ – cannot but help be received, at least at first hearing, as a statement directly from Scott to those who had been waiting for something to emerge from his own disappearance since the end of The Walker Brothers. However, that seemingly direct address does not turn out to be from a knowing pop star, or even a former pop star, to his devoted fans. The song ‘Rawhide’, which opens the album, is hardly an attempt at a return to pop, nor is it a wry look back at the form. It is instead... well, what the heck is it?

There are echoes in this first lyric of the well-known song of the same title, theme to a Western TV show about cattle drovers from Scott Engel’s teenage years – a kitsch classic the likes of which Scott Walker might have sung on one of his ‘lost’ albums of the 1970s. But the mysteries begin as soon as that first line draws us in:

This is how you disappear

out between midnight,called up

under valleys

of torches

and stars.Foot, knee,

shaggy belly, face,

famous hindlegs,as one of their own

you graze with them.Cro-magnon herders

will stand in the wind,

sweeping tails shining,

and scaled

to begin,SHUTTING DOWN HERE

Where are we now? If we try to parse it, it would seem we are quite literally in the dark. But a more fruitful question might be: where is Scott?

Returning to Said’s thoughts on late style, his comments on the great Greek-language poet CP Cavafy might equally have been written about the later lyrics of Scott Walker:

His poems enact a form of minimal survival between the past and the present, and his aesthetic of non-production, expressed in a non-metaphorical, almost prosaic unrhymed verse, enforces the sense of enduring exile which is at the core of his work... a form of exile that replicates his existential isolation.[v]

This ‘enduring exile’ that Said identifies in Cavafy’s poems resonates both with Scott Walker’s career at the time of Climate Of Hunter, and with many details of the album. Walker was forty years old when he wrote these songs, in the late summer of 1983. And by forty, his layers of self-imposed exile had only multiplied: from a Californian in London, to an Anglo-American in Copenhagen, a TV personality at the cinemathèque, a pop star without an audience, a Walker without Brothers. This ever-increasing isolation is, to me, the fundamental sound of Climate Of Hunter. The music on the album emerges from a silence that is something more than the hush of a carpeted 1980s-era recording studio. When the gates close on its drum hits, the sounds don’t just stop, they disappear – as had Scott before the album begins, and would soon again after its finish.

By his own account, Scott Walker had spent the years between Nite Flights and Climate Of Hunter ‘working toward what I call a silence, where this could come to me rather than me force it’, as he told a radio interviewer in 1984.[vi] ‘I was looking for the right atmosphere,’ he explained to another journalist in the same year. That atmosphere he finally found in ‘a cottage in the country. I looked in the paper and saw this workman’s cottage near Tunbridge Wells, so I rented it for two months, on my own. I put all of Climate Of Hunter together down there.’[vii] Those two months of isolation are carefully inscribed on the LP cover – ‘composed by scott walker, aug–sept 83’ – despite the artist’s reluctance to place anything but the barest information alongside his music. As he told Muriel Gray on the British TV pop show The Tube in a rare appearance to promote Climate Of Hunter, he was concerned that even titles ‘would lopside or overload’ his songs which were already ‘finished as they were’ – a situation that would cause Virgin Records to try and promote a seven-inch single called ‘Track Three’.

The soloists on the album were similarly placed in isolation, away even from the very tunes they had been asked to play – according to producer Peter Walsh in 30 Century Man, Scott’s melodies were ‘a closely guarded secret’ throughout the sessions. Without guide vocals, or any kind of lead chart, the studio players called in had to rely on something other than the usual, as they lay down their individual tracks. ‘It keeps everything a little more disjointed, there’s no chance of everyone swinging together too much – which is what I don’t want,’ Walker explains in the same documentary. Not that he didn’t communicate what he wanted from everyone involved – he just refused to do so in standard terms. ‘He was very graphic in describing what he was aiming for... using colours, shapes, dimensions, landscapes,’ recalls Walsh today. ‘At one point I remember he made a quick sketch for me of how he wanted me to modify the monitor mix.’[viii] Evan Parker remembers Walker explaining to him, over a bottle of Chablis, ‘I’m thinking about clouds of saxophone. I’m thinking more about Ligeti than anything else.’[ix]. Parker – a consummate improvisor – was comfortable with this kind of direction, and performs beautifully, playing with an openness that potentially relates to everything gathered around it. But guitarist Ray Russell, a pop and rock music stalwart, fared worse – his lead lines on the record really do sound like they were put down blindfolded, and sit stiffly in the mix without reference to anything else in the arrangement.

This disjointedness was deliberate on Walker’s part. Was it because it matched the atmosphere in which he had finally composed these songs? When he came back from his isolation in the country he immediately entered the most urban, and urbane, situation for a musician: an expensive recording studio with ‘the busiest session team in London’, as Peter Walsh describes the rhythm section he put together for the purpose. Parts had been scored, a full orchestra session booked, and yet, as arranger Brian Gascoigne recalled later, ‘Scott was extremely reluctant to let anyone know what was going to happen.’[x] The harmonies themselves masked his intentions. ‘What he’s after is the boundary between chords and discords,’ explains Gascoigne, sitting at a piano in a later video interview and demonstrating the type of ambiguity Walker would ask him not only to build into the arrangement, but then hold onto for sixteen bars at a time. ‘The strategy is to get this great seesaw going back and forth, and the pivot for it is to get the musicians into the no-man’s land between melody and harmony, conventionally [understood], and the squeaks and grunts of the avant garde.’[xi]

A logical comrade in this seesaw strategy might have been Brian Eno – indeed, Eno’s enthusiasm for Scott’s songs on Nite Flights is said to have had a hand in his new solo contract at Virgin,[xii] and if any records from the period share a sound with this second arrival of Scott the auteur, it would be the Eno/Bowie ‘Berlin’ albums. Bowie and Eno are both said to have been approached by Scott Walker as a possible producer for what eventually became Climate Of Hunter,[xiii] a situation that in either case might have shaped and contextualised his efforts with an eye on a larger pop audience. But Walker rejected these overtures. ‘His only reason was that he wanted to pursue his own ideas,’ recalled a still exasperated-sounding Dick Leahy, head of The Walker Brothers’ last label GTO, when asked in 1993 about the Bowie possibility.[xiv] As for Eno, Walker himself told the NME in 1984, maybe only half-joking: ‘I thought rather than destroying his career too I had to do one on my own.’[xv]

On his own, then, even while surrounded by colleagues in the studio, is how Walker went about constructing the album. This is especially palpable in the vocals, which Walker prefers to put down quickly, at the end of the sessions, with the minimum number of people present. That voice always seemed to rise above even the densest arrangements of The Walker Brothers and Scott’s first round of solo work, through its sheer strength and charm. But Scott’s own view is that his baritone ‘tranquilises people... so people stop listening to what they’re hearing.’ And what he wants instead on his late albums is for the voice to be ‘pitched, as the lyrics, vertiginously.’ All in the service of the lyric – and never comfortable. ‘It’s a genuine terror that I’m not going to get it right. And I only want to do it once or twice if I can. And I just have to absolutely get it. I fail lots of times but at least I’m trying.’

The result can send shivers down your spine, perhaps because the ‘genuine terror’ Walker creates for himself in the studio is communicated directly, or perhaps because he sounds so utterly alone as he faces it. ‘Ultimately, it’s just a man singing... I just want to get to a man singing, and when it has to have emotion, hopefully it’s real emotion.’

Which brings us back to those seemingly impenetrable lyrics. Eno, so engaged by this period of Scott Walker’s, would agree. In an extended interview included as a bonus on the 30 Century Man DVD, Eno talks at length about Scott’s strength as a lyricist: ‘I don’t find the lyrics at all problematic. In fact, I find them completely engaging... Normally I think lyrics I could do without. For me lyrics in most songs are a way of just getting the voice to do something... In Scott’s songs, that’s not true at all: lyrics actually draw you further and further into the music. And they’re so rich and full of ambiguity that they actually withstand listening to again and again, like music does. They don’t spell it out for you, so you haven’t “solved the problem” in the first two listens. That’s why I say he’s a poet.’

At the risk of trying to ‘solve the problem’, it seems worth taking a closer look at some of these lyrics on Climate Of Hunter, as if they were in a book of poems rather than on a record album. Walker works hard to place his words at the center of the music – speaking about his latest album, The Drift, he has said, ‘Everything is very low end, very high end, and the voice right in the middle, where it should be.’ So what did he place there, at the album’s core?

Exile and isolation would seem to be a key into the difficult lyrics of Climate Of Hunter, just as they explain much about the music. ‘Rawhide’, that opening track with its disorienting hunter-gatherer vocabulary, leaves an impression of loneliness on a vast, geological timescale. It begins with a cowbell moving across the stereo picture from right to left (east to west?), like cattle passing on the horizon, reinforcing the brief sense of familiarity generated by the title. But the shaggy upright figure who grazes with the herd in the opening lines seems to be not on the American plains, but in some kind of prehistoric ‘Cro-magnon’ past – at one with nature in a manner far beyond a television Western. Nevertheless, this is no pastoral scene by the time the strings enter, in anxious quick slurs, midway through the arrangement:

Freezing in red,

bent over

his ice-skinThe insomniac gnaws

in the On-Offs;he is glazed

in the hooves

all round.It is losing

its shape.

Losing its shape,

as the heat in your hands

carve the muscle

away.

‘The insomniac’ might be the hunter (and Walker has said that he himself suffers from nightmares), but I hear it more as the hunter’s victim. Either way, ‘in the On-Offs’ is like a line straight out of Beckett. On-Off suggests wake-sleep, or, given the images that follow, life-death, but as a plural it takes on the more disturbing idea of slipping repeatedly between the two states, back and forth, the jaw working all the while as it ‘gnaws’: death throes. The carving of the body in the next verse dissolves a stiff shape just as horns enter the orchestration, playing long, sustained tones against the strings’ tight runs, until eventually the strings, too, relax and join the horns in what feels like a peaceful coda. While Scott sings:

Motionless brands

burn into

a hipframeAs a saviour

loads sightlines

backlit by fires,on the ridges

of the highest

breeder

The last word of the song is a final, unexpected turn – shifting us from the appearance of a saviour on the highest ridge, to what then seems instead to be the owner of the high ground, or perhaps the highest placed in the human herd, the ‘highest breeder’ – and thus leaving us not in a state of salvation, but rather a kind of stable, permanent anxiety. Tomorrow will see the same death throes, the same victories and defeats of the ‘famous hindlegs’, the same disappearances.

This epochal opening to the album, situating us together with the singer in mythic time, could be taken as a grand, even stadium-rock gesture toward commonality – we’re all Cro-magnons here – but the details of the song ultimately work in an opposite direction. ‘Rawhide’, the television theme song made famous by Frankie Laine, similarly portrays a lonesome hero (played by Clint Eastwood, no less), driving his cattle ‘Through rain and wind and weather/Hell-bent for leather’, but that off-the-rack American fantasy depends on a direction – ‘Rollin’ rollin’ rollin’’ goes the refrain – and a goal: the big payday and party at the end of the road. Scott’s ‘Rawhide’ finishes instead with a puzzling, image. What might this ‘motionless brand’ be?

Consider the end of the Frankie Laine tune:

Keep movin’, movin’, movin’

Though they’re disapprovin’

Keep them doggies movin’

Rawhide!

Don’t try to understand ’em

Just rope, throw, and brand ’em

Soon we’ll be living high and wide

My heart's calculatin’

My true love will be waitin’

Waitin’ at the end of my ride

Rawhide!

If this idiotic lyric wasn’t in Scott’s mind as he wrote his own ‘Rawhide’, it had to be sitting there somewhere in his memory. In any case, placing one against the other would seem to elucidate some of that mysterious last phrase to Walker’s song. ‘Motionless brands/burn into/a hipframe’ is a frozen version of what was, in the Western ditty, a blur of activity (‘Just rope throw and brand ’em’), but it also serves as a kind of empathetic riposte to the bizarre instruction, ‘Don’t try to understand ’em’. These ‘motionless’ brands – they hover, in our mind’s eye, about to burn... whom? Perhaps they are directed at the hunter, rather than the hunted. Or are the two one? The ‘hipframe’ they mark might be cattle, as seen on TV – but I can’t help but also hear an echo in that phrase of Swinging London. Wasn’t Scott himself branded in the ‘hip frame’ – the pop frame of reference – and left motionless in that moment he spent at the top of the charts?

This biographical reading of the ending is likely going too far – a canard that matches the invitation to read the opening line, ‘This is how you disappear’ as a personal statement from Scott, the former pop star. But behind it is a feeling, more likely intended by the singer, of identification with the branded. The motionless brand is a nightmare image, a permanent threat – an injury about to happen, as opposed to the action-figure GI Joes of ‘Don’t try to understand ’em/Just rope, throw, and brand ’em’ who inflict their harm on others, rather than themselves. So who is the hunter, who is the hunted? By the end of the song, that would seem to be an open question, as the lyric’s ambiguities leave the two terms confused.

Regardless of the rhyme of these associations with the author’s ideas, here we are for sure, in the climate (mood/spirit) of hunter, looking for sense in these difficult, openended lyrics of Scott Walker. As Said writes of Cavafy, Walker has deliberately placed us in ‘an ambiguous but carefully specified poetic space in which to overhear and only partly to grasp what is actually taking place.’ That carefully specified space – an exile’s place, in Said’s terms – is I think delineated throughout the album. As überfan Lewis Williams points out, the structure of Climate Of Hunter is symmetrical (something much more readily apparent on LP than on the later CD reissue): ‘Side two... mirrors side one too closely to be anything but intentional,’ he writes.[xvi] Each side of the original LP has four tracks – the second of which features Evan Parker on sax, the third of which features Ray Russell on lead guitar, and the fourth of which omits the rhythm section otherwise featured throughout. It is easy to find many such parallels – the cowbell that opens side one, with the bass harmonics that open side two, and so on – but what is more interesting to me here is the idea that the LP feels constructed like a physical space. In this regard, the tracks listed only by number may not be as blankly titled as they seem – since the one thing that is made absolutely clear about them is their place in the sequence. “Track Three” was a rather absurd title for a single, but what could not be missed even in isolation is that the song properly belongs to a carefully specified space: the space of the album.

Images of this space – the place of exile – occur throughout the album’s lyrics, but are especially important to the last tracks on each side: ‘Sleepwalkers Woman’, and the sole cover in the collection, ‘Blanket Roll Blues’. If ‘Rawhide’ is a disorienting opening for the long-time Scott Walker fan, ‘Sleepwalkers Woman”’ would seem to be their reward for making it to the end of side one. A flat-out gorgeous orchestration, with familiar touches from Scott’s earlier career, like reverb-heavy plucked strings over long sustained bowed ones, here Walker allows himself the same lush romanticism that the album’s first tracks avoid so assiduously. The harmonies have tension, but the washes of chords make the song feel like one long cadence – it resolves again, and again, as Scott reaches the end of each verse. The lyric, too, resolves more than once: ‘For the first time/unwoken/I am returned’ is the conclusion to the first half of the song, a phrase sung twice and then repeated melodically by the orchestra a third time – an instrumental device in direct contrast to the preceding tracks, which feature solos recorded without any reference to the melody. The journey toward this resolution begins:

In the time

of an exile,from the jails

of another,where soundings

are taken

raw

to his

eyes.

The second half of the song similarly begins in a place of isolation:

He arrives

from a placewith a face

of fast sun.Arrives

from a space,his refuge

overrun.

And resolves again with this idea of ‘return’:

For the first time

forgetting

I am returned.Her mind moved

on the silence

I am returned.

The development expressed here – from exile to return – would seem to be achieved not only in the lyric to this song, but also on this side of the album. ‘Sleepwalkers Woman’ – no apostrophe, so we might read it as two consecutive nouns, as well as with the implied possessive – is a destination as ambiguous as the starting point of ‘Rawhide’, but it is clearly an arrival. ‘There are no voices here’, Walker sings, about the place he finds himself at the end of side one. ‘We have entered deserted.’ Where the singer has entered is as ambiguous as where he began, but as Eno says about Scott Walker’s lyrics, ‘It’s not to do with meaning, it’s to do with making something happen. It’s not to do with telling someone something, it’s making something happen to someone, which is what you do with music as well.’[xvii]

In other words, we may not be able to parse exactly what is meant by the arrival expressed in ‘Sleepwalkers Woman’, but we nonetheless feel something of what has happened to this singer who begins, ‘This is how you disappear’, and finally declares, ‘I am returned’.

This process of side one doesn’t continue linearly on side two, so much as repeat in a cyclic variation. ‘It’s a starving reflection’, is how ‘Track Five’ begins, with a meditative intro that is then interrupted by a series of almost frantic images of motion – some of them mirrors of phrases already encountered in ‘Rawhide’, such as ‘gnaw’ and ‘On-Offs’:

WE CHEW UP

the blacknessto some

high sleep

travel,a faster

silence.One

to go long

again,in the going-

-gone again.Full stare passages

striking less face;

outside

on the move

a shattered heart

pace

This forward-moving lyric is set to a quick and simple backbeat, a kind of disco march, but in the latter part of the song the keyboard starts to push the harmony in surprising ways, building more slowly and dramatically toward a cadence that never quite arrives. Horns finally enter, as they do at the end of ‘Rawhide’, just as an image of melting is again introduced:

And the heat

from the shore,

melts down

to receive us;floodlit foreheads

howled open,

and so nearly

blessed,as they soften

round dog-joys

of unfinished

strangers,rubbed out

on a pointafterburning

The body/animal images here rhyme with ‘Rawhide’ as well, but the point of view seems more resolutely from the hunted rather than hunter – marched down to a floodlit place, and ‘rubbed out on a point’. Is it a slaughter? Or perhaps another view of branding; this time not in anticipation of pain, but rather its ‘afterburning’.

Whether this reflection between songs and album sides was deliberate on Walker’s part or not, the record continues through the end to toy with our expectations of direction. Just as the ‘shattered heart pace’ of ‘Track Five’ gives way to a false cadence, an ending that’s never quite reached, the entire sequence builds toward a conclusion, ‘Blanket Roll Blues’, that leaves the singer in the same isolated and dislocated space described by – that first line again – ‘This is how you disappear’.

When I crossed

the river,with a heavy

blanket roll,I took nobody with me,

not a soul.

I took

a few provisionssome for comfort

some for cold,but I took

nobody with me,not a soul.

This closing song is the only one on the album not written by Scott Walker. Marlon Brando sings it in the Sidney Lumet film The Fugitive Kind (1959) – Tennessee Williams’s own adaptation of his play Orpheus Descending (1957), which reimagines the Orpheus story in a Gothic Southern town, with a guitar-carrying drifter as the archetypal poet-singer. Walker told a radio interviewer at the time of Climate Of Hunter’s release that this song had been ‘in the back of my mind for years and years... and it seemed like the perfect sort of period at the end of all this.’[xviii] That period marks an arrival, just like ‘Sleepwalkers Woman’ – the singer has already ‘crossed the river’, the past tense of the blues matching the ‘I am returned’ refrain that finishes side one. But this time the ‘carefully specified poetic space’ that Said finds in Cavafy is more clearly delineated (Tennessee Williams being a much more explicit writer than Scott Walker). It is a space occupied only by the singer, even as he addresses us from it – a place of loneliness, and exile. It is where we began.

[i] In Cavafy, CP (trans Edmund Keeley & Philip Sherrard), Collected Poems (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1992)

[ii] Scott Walker quoted in 30 Century Man (dir Stephen Kijak, USA 2006). Except where stated, all Walker quotes in this chapter are taken from interview segments in this film.

[iii] Said, Edward, On Late Style: Music And Literature Against The Grain (London: Bloomsbury, 2006)

[iv] Said, On Late Style.

[v] Said, On Late Style.

[vi] Walker quoted in interview with Alan Bangs (British Forces Broadcasting Service radio, 1984).

[vii] Cook, Richard, ‘Scott Walker: The Original Godlike Genius’ in New Musical Express (17 March 1984).

[viii] Peter Walsh interview with the author, [DATE]

[ix] Evan Parker interviewed in 30 Century Man.

[x] Brian Gascoigne quoted in Watkinson, Mike & Anderson, Pete, Scott Walker: A Deep Shade Of Blue (London: Virgin Books, 1994).

[xi] Brian Gascoigne interviewed in 30 Century Man.

[xii] Watkinson & Anderson, A Deep Shade Of Blue.

[xiii] Watkinson & Anderson, A Deep Shade Of Blue.

[xiv] Watkinson & Anderson, A Deep Shade Of Blue.

[xv] Cook, ‘The Original Godlike Genius’.

[xvi] Williams, Lewis, Scott Walker: The Rhymes Of Goodbye (London: Plexus, 2006).

[xvii] Brian Eno interviewed in 30 Century Man.

[xviii] BFBS radio interview, 1984.

Loved yours and Naomi's cover of The World's Strongest Man. Beautiful!

I haven't listened to the album in years, but even so this was fantastic. Thank you.