Originally published, in an edited form, by Talkhouse (April 24, 2017)

Recording at home is a remarkable luxury for a musician, in terms of time: Every apartment becomes an Abbey Road, with tape decks at your disposal any hour of the day or night.

But Abbey Road must be quiet.

“Opening” a mic into a given space, as the engineer’s term puts it, is a great way to sensitize oneself to the subtle sounds all around. A plane passing high overhead. The vibrations from your refrigerator. The cat jumping down from the bed in the next room.

John Cage taught us that there’s no such thing as absolute silence. At minimum, you still have the sounds of your own body to contend with. And even Abbey Road is susceptible to unintended noises — witness the air conditioning audible at the end of “Sgt. Pepper’s” grand final chord.

But home recording doesn’t exist at the far end of the sound/silence spectrum. We tend to live smack in the middle of a world of sound. I imagine all home recordists have their own specialized ways of dealing with this problem while the tapes are rolling. (My solution is to work in the dead of night, which means in the freezing cold if it’s winter.) Even after the record’s done, an alertness to surrounding sounds remains, however. You can’t shut off your ears. And once you’ve listened closely — very closely — to all the sounds in your everyday environment, they can be impossible to unhear. This may be an occupational hazard of sorts.

As I write, I’m hearing the sounds of a gently rainy Saturday on my street: The odd passing car rolling over wet pavement, the hollow ring of the drain pipe, the creaks of an old house absorbing more humidity than it did yesterday, stretching and cracking not unlike my own aging joints.

Many of these sounds I find lovely. I am happy to have my ears open to them. But then there are the extremely unsubtle sounds that surround us, which we have to work to shut out rather than to hear. Like the truck making a delivery to the church across the street, shifting into reverse.

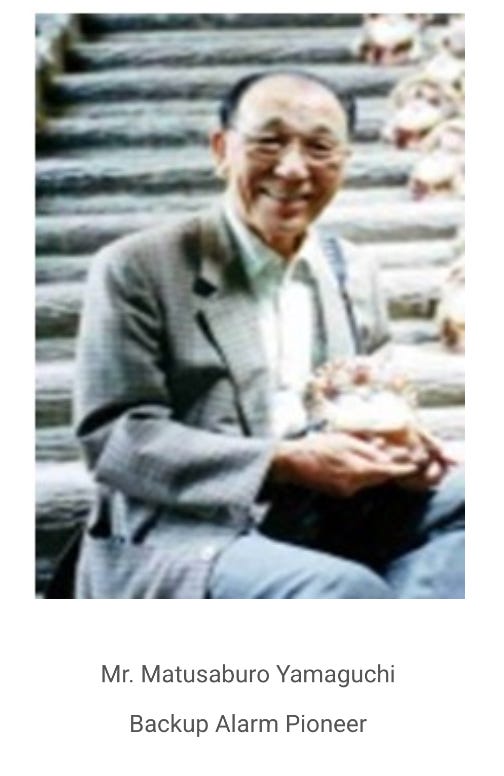

The back-up alarm is a sound designed not to be ignored. It was invented in 1963 by a Japanese engineer, Matsusaburo Yamaguchi, who was looking for a tone that would rise above ambient sound and necessarily command one’s attention. It is placed in a part of the sound spectrum that we do not use for normal communications, not least because it is so unpleasant. And to make sure that it can be heard amid a din — as on a construction site — it is extremely loud. Loud enough to be heard even by those with hearing loss.

It is, in other words, the most annoying sound in the world.

Yamaguchi-san was successful, I am sure beyond his wildest dreams. His 1000-hertz, 100-decibel tone is everywhere. The UPS truck with yet another Amazon package. The SUV parallel parking. The Bobcat patching a pothole on someone else’s street, off in the distance, which is also filled with maneuvering SUVs and Amazon deliveries. Yamaguchi’s sound, pitched to rise above all others, has become an ordinary part of our aural environment.

It can never become a subtle one. And yet… how often do we pay attention to it? Have we been trained, by its ubiquity, to tune out a tone that by definition could not be tuned out?

What if that 1000hz, 100db sound has woven its way so deeply into our aural environment that we no longer hear it distinctly without special effort? What can we do to warn one another of impending doom?

Or is this endtimes as we are now experiencing them: inaudible, screeching, and heading at us in reverse.

Listening to: noise-cancelling headphones

Cooking: cucumber with umeboshi, konbu and lime