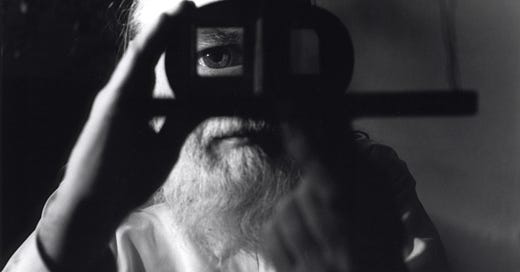

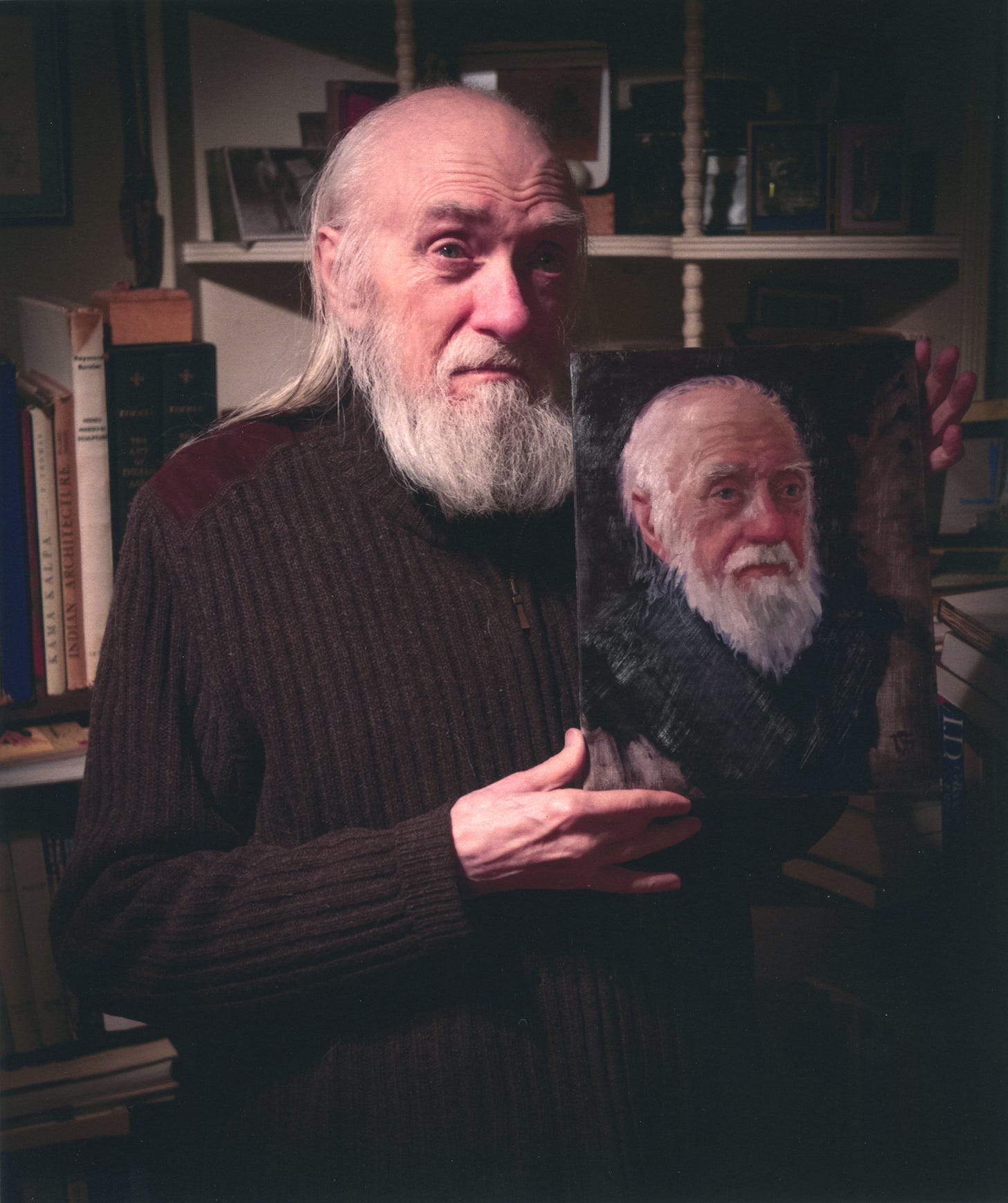

Poet, novelist, collage artist, translator, publisher and teacher Keith Waldrop died in July 2023, at age 90. This month, a large group of friends, students and admirers gathered to honor him at Brown University, where he had taught for decades. We each chose different parts of Keith’s work to share - Naomi and I sang a song he wrote with his friend Christopher Montgomery.

Music was so important to Keith, he was forever listening to records or attending an opera or ballet, yet he did not play an instrument and claimed he could not sing. He also, so far as I know, never wrote anything formal about his deep connection to music, though it came up again and again in conversation. I gathered the following statements from various parts of the extended interviews Peter Gizzi conducted with Keith from 1993-97. These were first published in the journal The Germ, reprinted in a lovely book devoted to both Keith and Rosmarie Waldrop, edited by Ben Lerner and titled Keeping / the window open (Wave Books, 2019).

As the selection begins, Peter has asked Keith the age-old modernist question: Eliot or Pound? The answer is Pound, but Keith goes on to say…

*

When I was in college there was another influence that’s a little more unusual. I started listening to French songs, recordings of Juliette Gréco – and I was quite bowled over by what she was singing. So I looked up the texts. Many were by Prévert and the ones I liked best were by Raymond Queneau. So I looked him up, though I could barely read French. That’s when I started translating poems. I had to translate them – so that I could read them. Anyway, Queneau was probably the greatest influence on my early work. Outside of the obvious.

And it isn’t just right then, it’s over the years that Queneau has been a tremendous influence, because he was someone who taught me – I could have learned it elsewhere, but in fact I think it was from him that I learned, first of all, you don’t have to decide whether you’re going to be serious or unserious. You simply don’t have to make that decision. Romantic or classical. Comic or tragic. And you don’t have to decide whether you’re going to “think” or to “feel,” to use high diction or low diction, or whatever. I mean you combine these things – any things – if you can do it (it’s a problem of form). Which he could. Which I couldn’t, but it seemed worth a try.

I’ve often found “meaning” tyrannical. I think meaning is always an element in the sound that poetry is made of, but it’s only one of the things that determine how the words sound.

I’ve always had the notion of – well always isn’t quite right, but from early on – of combining verse, prose – combining things as different as possible. Combining free verse and metrical verse, for instance. In my first book you can see there are places I tried that. Even at that time I had the urge to combine them. And it didn’t work entirely, but I was trying… I’m interested in poets who start with the spoken language, and then make a new written language out of it. There’s Queneau again, of course, but also – for instance – Robert Burns.

Poetry, for me, is an art of speech, of sound, and always an art performed. But I don’t mean necessarily publicly, or even audibly. Reading “silently” is a physical act. The sound is in our mouths, our tongues, in our throats. For a poem to exist, that reader, that theater, is necessary – and, as in any playhouse, the text is at the mercy of its immediate interpreter.

Words are always in space, always placed, always somewhere relative to the speaker/reader (in front, behind, to the left, above…). And also in a dynamic relation (approaching, receding, attacking, hiding…). If it’s a written text, the position of the words on the page is a factor. And all of this (all of it, after all, theatrical) influences – or rather, is part of – the sound.

There are many composers whose music I like and some, of course, more than others. I like Monteverdi, Mozart, Schubert, Berg, Cage… Indian music, especially Carnatic. Jazz. Of contemporary composers, I’m very fond of Ashley and Mumma, whom I feel close to. I love their work. The ONCE group, which they founded, became most distinctive as a group just after we left Ann Arbor, but it began while we were there. It must have been 1961, 62, somewhere along there. Gordon Mumma was working in a bookstore at the time and it was through him that I met Ashley. They were talking about doing a concert of new music. I recommended that they do several concerts and call it a festival and then people would pay more attention to it. And that’s what they did. I’m not a musician and had nothing really to do with it afterwards, but I always felt glad to have been there at the beginning… Mumma and Ashley did music for my plays in Ann Arbor. Not plays that I wrote, but that I gave.

I’ve always been disappointed that I can’t do more with music. I can’t play any instrument. (I inherited my mother’s vertigo, but not her talent.) I’ve always thought of music as the paradigmatic art. When I think of art, it’s music I think of. When discussing poems – or prose texts, for that matter – the terms that come to me are rhythm, melody, harmony.

Music is the art that I most enjoy, most admire, most love… Anyway, it’s music that I most like – well, except maybe for ballet…

Listening to: When the Roses Come Again, by Daniel Bachman

Cooking: round foods

It's odd, but without knowing it, I purchased and read his translation of Baudelaire's "Paris Spleen," around the time he passed away. It's a great translation. Wonderful tribute to him and his work, and his love of "sound."

I'm completely unaware of Waldrop, and am not much of a poetry fan in general , but his remarks here are very interesting; cool to find out about the Ann Arbor OPEN group, too.

Mainly I wanted to comment about how great Daniel Bachman's new album (which you tag at the end) is!