Radio, Radio

I’d like to praise a digital technology, for a change…

During lockdown, I’ve been listening to more radio than ever. Not podcast, but broadcast – it’s communication in real time that I’ve been craving. Voices on the radio have been filling in for missing voices that are usually a part of my day. Working entirely from home, going out as little as possible, and traveling not at all has turned me into a bit of a shut-in; and shut-ins famously like radio.

It’s not just any radio that’s done the trick, however. I’ve been listening in particular to the BBC – which, thanks to their superbly designed app, BBC Sounds, is now equally accessible to me as my favorite local AM station.

Ironically for someone who has written elegiacally about analog media, internet radio has made a dream from my childhood finally come true. Growing up in 1970s New York City, my first technological purchase was a multiband radio with shortwave, which I thought would let me hear round the world. But instead its shortwave bands picked up only static and occasional mumbling men’s voices, most likely no further away than the tugboats passing by on the East River. AM actually provided a more legitimate long-distance thrill when, on certain nights, the weather patterns and cloud cover combined to bounce waves from a ballgame as far away as Baltimore, with its exotic local beer and car dealership ads.

Eventually, I gave up on the idea of long-distance excitement from radio and left the multiband dial fixed on FM, where I could indulge a different kind of exoticism through late night DJs on WNEW’s “progressive rock radio,” WPLJ’s “album-orientated radio,” or the confusing talk I knew I could always find on WBAI.

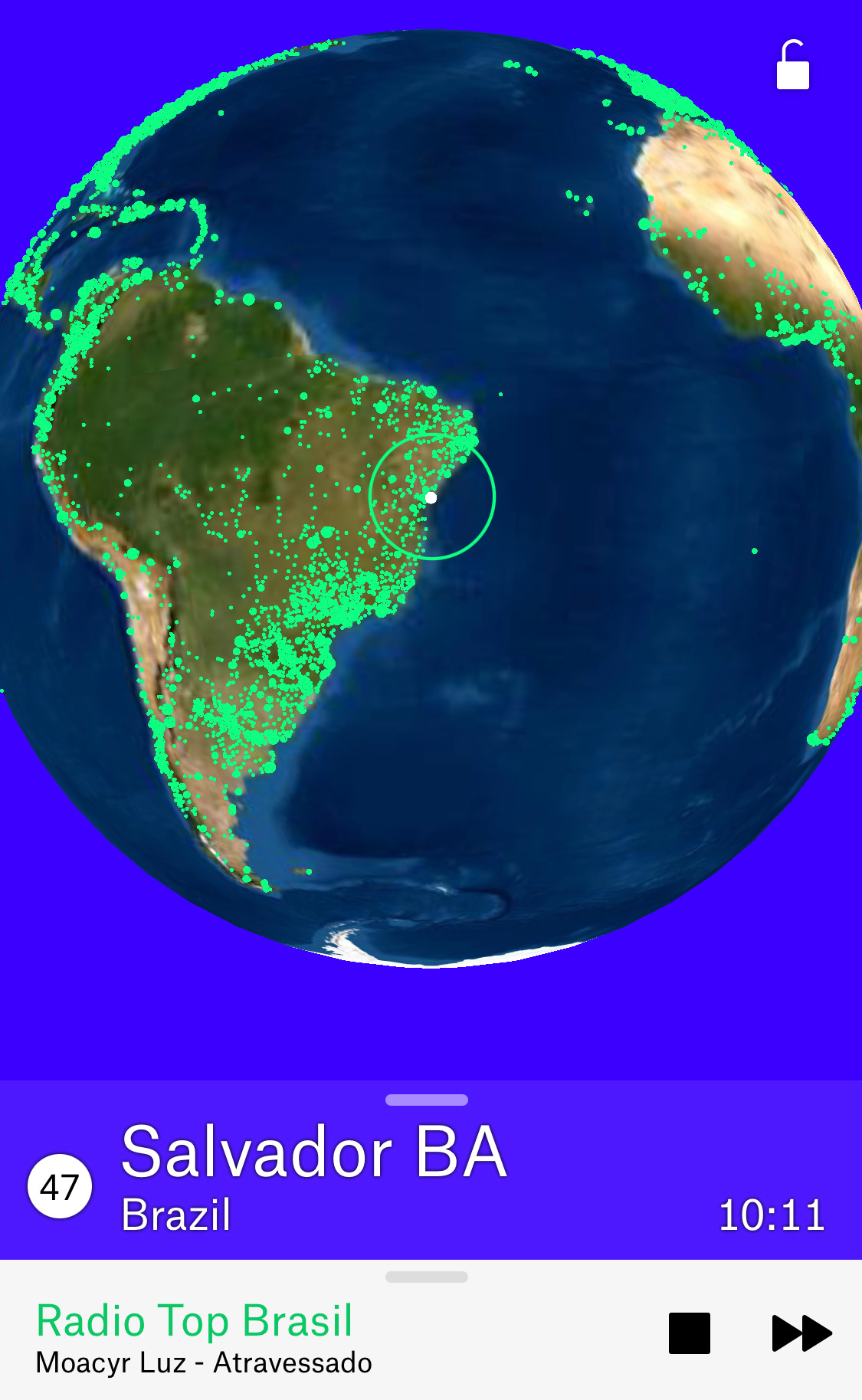

Today, the app Radio Garden is the shortwave I had imagined existed, but didn’t – it invites you to literally spin the globe, listening to whatever is playing that moment at every glowing point of broadcast. This feeling of simultaneity – across time zones, across continents, across cultures – is dizzying.

Indeed the choice on Radio Garden is so great, and making that choice so much fun, I find myself spinning it way more than listening to it. Why stop wandering? It’s a virtual version of what must happen to those epic travelers who not only value the journey over the destination, but seem addicted to it.

A more colonial version of this radio globetrotting, where all destinations feel possible and yet are always measured from one “home country,” is on the BBC. I listen mostly to the World Service, a broadcast meant to be heard at a distance from Britain – where terms and celebrities peculiar to the Isles are carefully defined or qualified by context, where less time is spent on parliamentary politics and hardly any on cricket. But I find myself tuning in frequently also to its domestic channels, especially Radio 4 for its magical litany of the Shipping Forecast (Naomi and I even wrote a song about that). And on the way there, I might pause for a jolt of Gaelic on Radio nan Gàidheal or Welsh on Radio Cymru, just to feel the strangeness of it in my ears.

On the World Service itself, I feel my ear for the English language stretched by native speakers from around the globe: Africa, Asia, the Caribbean, the Subcontinent... Decentering my local version of English makes it feel both more particular and less parochial, as it connects to a sprawling, flexible, fluctuating tradition. American English is flat - the occasional broad parody on the BBC makes that clear. And flatness has the illusion of limitlessness when you’re in the middle of it. The same is true of our politics: hearing US news reported between headlines from other places is a relief to the monotony of a CNN crawl. It’s a big world out there, with a lot of concerns, but you’d never know it from a US chyron, endless as the prairie.

There’s another relief listening to the BBC, for my American ears: No ads. And not only no ads, but no slogans from underwriters of public broadcasting – which, in the era of corporate branding, have become largely indistinguishable from ads, and to me at least, equally compromising. (“Facebook is a financial supporter of NPR” was a disclaimer inserted in NPR news bulletins last week, as it reported on Facebook’s systematic destruction of reliable news sources.)

I am American but not so naïve to think that there are no compromises in a state corporation like the BBC, whose omissions have been so broad at times as to include all of popular music (which gave rise to pirate radio, until the BBC turned around and hired its best known DJs like John Peel). But again, it’s the contrast with our system that I find refreshing – a contrast so stark that in radio history these two funding models are sometimes referred to as the “American plan” of paid advertising and the “British plan” of usage fees. When radio emerged as a new technology, the two states took fundamentally different attitudes toward it. In the UK, the government looked at radio as communication and put it under the aegis of the Post Office. In the US, radio was a commercial invention for the market to do with whatever it might.

Of course the US marketplace includes more than Corn Flakes (which you shouldn’t be purchasing right now, Kellogg workers are on strike!) – it eventually developed our heroic network of community and college stations, many of which operate outside the commercial system, as well as our version of national public broadcasting, heavily supported by corporations and philanthropy built on corporate fortunes. But we have nothing noncommercial with anything near the resources of the BBC - the quality and reach of its programming, without audible sources of revenue, are a gift to anyone within earshot.

As a listener, I find this lack of interruption on BBC radio invites true immersion in the material – it’s the difference between watching television and going to the movies. When, for example, Chris Watson takes us on a field recording trip with one of his “audio postcards” on Radio 4, the immersion is utterly transporting - removing us from our current environment and placing us in another, with nothing to snap us out of the illusion until the show ends.

Travel via audio is another form of decentering, this time of our physical environment. I have been especially grateful for this during lockdown, whenever rootedness begins to feel too much like entrenchment. Listening to distant radio broadcasts has successfully destabilized my aural environment by broadening its context, rather than narrowing it for commercial goals. It’s a use of digital media I wish more of our platforms would emulate.

Listening to: Iggy Pop DJ on Radio 6 Music

Cooking: Apple crumble

i first bought a shortwave radio about 20 years ago, which I think was kind of the tail end of it... but I definitely recall being able to pick up overseas stations. Internet radio never really did it for me, though - I don't really listen to radio in any form anymore, which is kind of sad.

It's not live... but I've been addicted to this John Peel Roulette site... https://www.monkeon.co.uk/johnpeelroulette/