Originally published by Artforum (October 2006)

In the right light, any composed music might for a moment look like Conceptual art — the composer’s idea, separate from each particular incarnation of it, reigns supreme in the platonic world of written scores. Italian composer Giacinto Scelsi (1905–1988) spun the thread between idea and performed music even finer, in quest of an act of creation he eventually refused to call composing at all, preferring the model of a spiritual medium, or “receiver.” Perhaps, at a certain point in his quest, that thread snapped — which would explain some of the confusions and controversies surrounding Scelsi’s work since his death. There is Scelsi’s idea. And there is Scelsi’s music. How the connection is made between the two is an enigma. Indeed, such mysteries were among the principal subjects of a preconcert conversation at Columbia University’s Italian Academy on July 21 between music critic Paul Griffiths and cellist Frances-Marie Uitti, who then performed Scelsi’s suite for solo cello, Trilogy: The Three Ages of Man (1957/65). (Her recording of a portion of this work was recently released by ECM on a CD of Scelsi’s music titled Natura Renovatur.)

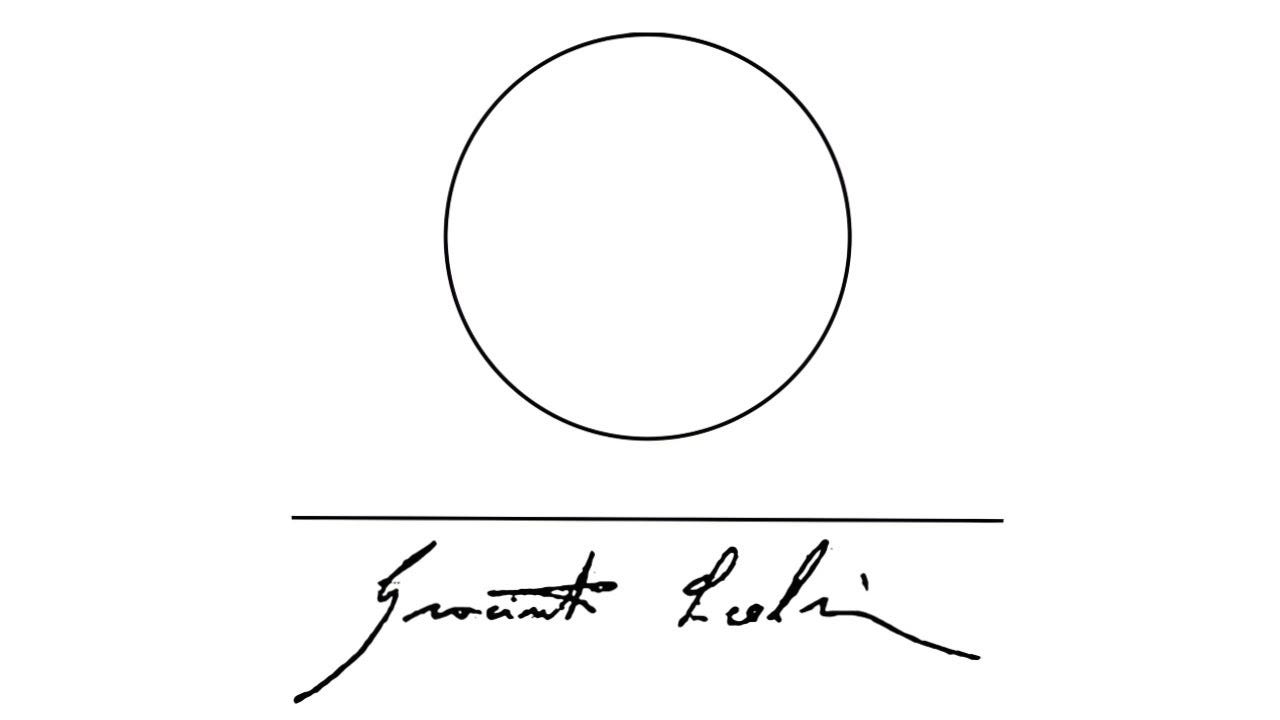

There are many tantalizing stories — and few verifiable facts — about Scelsi, a man who famously refused to be photographed and who signed his name with an empty circle above a line. He was born into a noble Italian family and lived on the Palatine Hill, overlooking the Roman Forum. Before World War II, he spent much of his time in France and Switzerland, living the life of an artistic aristocrat. He studied music with a disciple of Schoenberg and with a disciple of Scriabin. He visited Monte Verità, delving into the mysticism of Helena Blavatsky, G. I. Gurdjieff, and Sri Aurobindo. He became familiar with key figures of the European avant-garde, especially those on the decadent fringe, like Jean Cocteau and Henri Michaux. And, like his friend Michaux, he traveled east — to Egypt, to India, and, some say, to Tibet. He published three books of poems, in French. And he began to publish scores.

But then something happened. During or just following World War II, which Scelsi sat out in Switzerland, he underwent a crisis. His marriage ended, and so did his career as a routine avant-gardist. Recovering in a sanatorium, Scelsi found himself playing one note on the piano over and over and thereby discovered a new use for his music: meditation. Returning to Rome, he began to create music anew — but no longer on paper. In the early 1950s, Scelsi bought an electronic instrument called the Ondiola, along with a Revox tape recorder. And in his palace on the Palatine, he began recording experiments in musical meditation and improvisation, some seven hundred hours of which survive.

However, those recordings are not Scelsi’s music, at least not by his own reckoning. Scelsi’s recordings, never made public, were transcribed onto paper, written into scores by a composer he employed toward that end, Vieri Tosatti. After Scelsi’s death, Tosatti published an article titled “Giacinto Scelsi c’est moi,” and it caused a scandal. It is undeniable that Tosatti is in fact the author of Scelsi’s written music. But that written music is a transcription of improvisations taped at via San Teodoro 8, by a solitary Giacinto Scelsi.

What, then, is Scelsi’s music? Is it the flow of musical ideas he “received” while improvising on the Ondiola? Is it his taped performance of that inspiration? Is it Tosatti’s transcription, interpreting that taped performance? Or is it a performance by a given musician, interpreting the transcription that, in turn, interpreted the improvisation?

Frances-Marie Uitti is a living connection to Scelsi, one of a select group of musicians he invited to work with him. She is also perhaps the only person who has listened to all his tapes, having catalogued them for the foundation created to preserve his art. And she has no doubt about what it is that constitutes Scelsi’s music: “I see it as one continuous thought,” she said in a private interview before the event at Columbia. “He would say it was inspired by forces greater than himself. He considered himself a messenger, and indeed he passed that message on to other musicians, who then embody the music; they embody and amplify it again. What he received as a pure, direct, Ondiola sound then becomes orchestrated into a mass of shimmering instruments, beating against each other and slowly permutating… I think it’s like one massive breathing body — the embodiment of a metathought.”

Uitti’s own performance that evening was like a metathought about the cello. In the appropriately Italianate theater, she droned, scraped, and sang her way through the three exceedingly difficult solo pieces Scelsi had dedicated to her. At no time during the performance did Uitti simply play her cello. She bonded with it, cloaking herself in it like Charlotte Moorman. Or she sat apart from it, glancing at the written music on the stand, then challenging the instrument to do more, looking almost desperate when it didn’t seem to say it all — until it did.

This is clearly Scelsi’s music the way he intended it to be heard. He had the means to have easily arranged things differently — releasing his own recordings, for example. Instead, he left his legacy in the hands of a few handpicked performers, including Uitti, vocalist Michiko Hirayama, bassist Joëlle Léandre, and pianists Marianne Schroeder and Aki Takahashi (all virtuosos, all women, and all quite young when they met and worked with Scelsi, who, as Uitti is quick to point out, “could have been my grandfather”).

What kind of music is this? It is, as Uitti told me, “the spiritualization of a medium of art which is already so ephemeral. It’s the dematerialization of sound.” Which explains why Scelsi’s own recordings remain locked in a room on the via San Teodoro. Sound, so easily captured on tape, stamped out on CDs, or downloaded onto our computers, can be mistaken for music. But music, as Scelsi understood it, is something streaming by us always, without form until, as on that late July night, it is temporarily embodied by a person holding an instrument, staring at circles and lines, and breathing.

Listening to: Hayden Pedigo, Live in Amarillo Texas

Cooking: last of the tender greens before a heat wave