Sans Papiers

I was raised by my father never to share my social security number with anyone but employers and tax authorities; not to answer random questions put to me by police or others in uniform; and not to produce ID when asked unnecessarily. This is America, he explained, where no one has the right to ask for your papers.

My father was very much a patriot. Not a wild-west patriot with a pickup and a second amendment bumper sticker. A New York City immigrant patriot, who learned the Constitution to pass his naturalization exam, and never owned a car. I grew up in Manhattan, and my father encouraged me to treat its streets and parks and public institutions as my own, in common with everyone else who also had every right to claim them as their own.

These constitutionally guaranteed rights of anonymous citizenry that I was taught to flex seem like a thing of the past at this moment. Not that they were ever easy to assert; I’ve gotten myself in a fair number of scrapes over the years, exercising these rights with those who didn’t acknowledge them. I’ve also been called paranoid along the way, including by some whose judgement I esteem. I’m certainly not the most trusting of souls; guarding one’s constitutional rights is a full-time job.

As is guarding everyone else’s. My father wanted me to become a lawyer, for that very reason. When I refused, it was but one of many conflicts we had with one another – careful what lessons you teach your child, lest you find them applied to you too. A relation in France once laughed long and hard at my father calling me “insolent” when I was just two years old; it became a family story repeated enough that it’s among my memories even though it occurred before I could solidly form them. How could I know what insolent meant, at two? And yet I’ve never not known; it means refusing to produce ID when asked unnecessarily. It means dropping that ID at a motorcycle cop’s feet, when it seems you have no choice but to produce it. It means bending down to pick your ID up from next to that cop’s boot, and realizing the grave mistake you may have just made. It means relief when you don’t get a kick in the teeth but instead a summons to appear in court so you can now tell the judge, as the cop put it, why you dropped your ID instead of handing it respectfully to an officer of the law.

It also meant, at least to a white male Harvard student living in Massachusetts, that said judge would scold the cop instead of me, and throw the case out of court.

The law worked that time just as my father said it would. I see now that I must have unconsciously staked my privileges against the cop’s, and felt ok about the odds. Nevertheless I was always aware – despite having been born here – that I was an immigrant. We all were. The cop was Irish, the court clerk was Irish, the judge was Irish too. “Nice Irish name,” the judge said when my case was called, to laughter from everyone in the room but me. I was busy wondering what the sentence guidelines were for insolence.

Insolence is its own punishment, I have learned. Not that I haven’t been insolent frequently since – you might be reading this now because of my history of insolence with the powers that be in the music industry, like Spotify. But insolence comes with the hidden costs of non-compliance. And those costs have been rising sharply in recent decades.

Today, non-compliance with violations of the civil liberties that my father taught me to protect would require clicking “no” on every website’s terms of use. Do I consent to their violations of my privacy through electronic surveillance? NO! Do I need access to the information and services that these websites provide? YES! That access is no longer mere convenience – at this point, it is required for almost any engagement with our commercial society. Try using cash exclusively and see how far you get through your day. Even venues pay us virtually now.

This elimination of our right to anonymity in the commercial sphere has been mirrored by a steady degradation of that right in the legal one. Would a judge back up my non-compliance with the police today? Would I even make it to court? Would I survive the encounter without a kick in the teeth, without being tagged a domestic terrorist, with my body and my freedom intact?

Those who did not have the privilege of my skin color and my education may never have made it through that risky encounter with police unscathed. For this reason they might have been given very different instructions from their elders about how to deal with such a situation. The civil liberties I learned as inalienable were always highly conditional, in other words. They have never applied to everyone in our society.

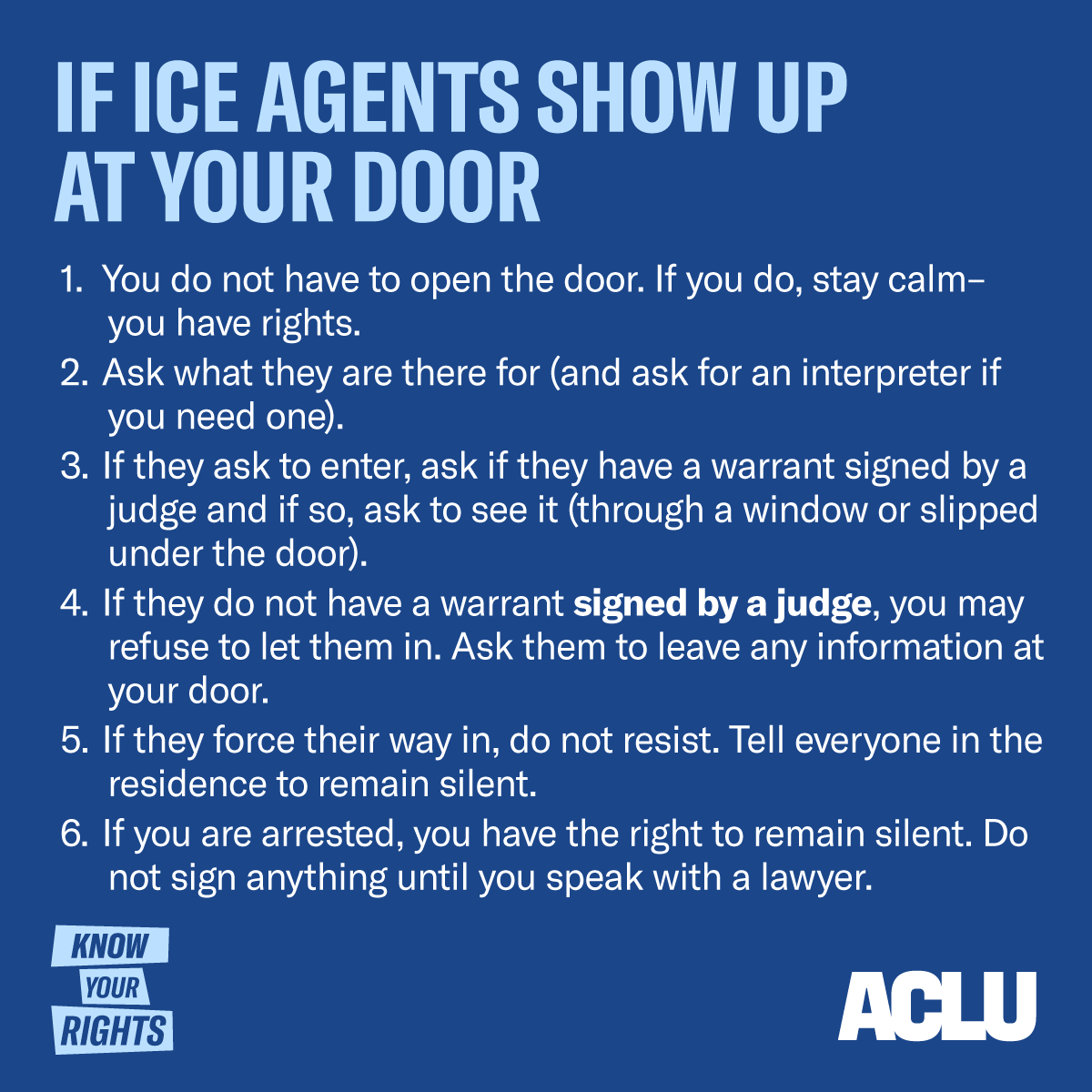

But what I realized only recently was that the rights my father taught me to safeguard in particular – fourth amendment rights, “The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures” - do not only represent a disinterested democratic ideal. They are also highly specific to my family’s historical vulnerabilities with regard to the state. My father’s instruction was, in a way, a version of “the talk” delivered by someone who had lived for years without valid ID. If you don’t have legal ID, what more clever response to the demand for producing one than refusing to show it on constitutional grounds?

My grandfather preserved all his legal documents in a locked monogrammed briefcase, and when he died in 1969 my father took this briefcase and put it deep in a closet in our family’s apartment. I knew it was there, but I also knew not to ask about it. It was some fifty years later that it was finally dragged out of the closet, broken open, and its contents examined. There were my grandparents’ Polish passports, with the precious Japanese transit visas inside that had saved their lives by granting the family exit from Europe during World War II. Without these carefully folded, handwritten and stamped pieces of paper, my grandparents and their two young children - my father and my aunt - would almost certainly not have survived the Holocaust.

I knew that story well, of course. But it was hair-raising to see the physical documents on which it depended. They are so fragile. Literally slips of paper.

But there was another part of the story that the documents in my grandfather’s briefcase told by omission, and this had to do with US immigration. The paper trail my grandfather preserved goes blank precisely six days after the family’s arrival in the US from Japan, when their initial entry visa (granted by the US embassy in Tokyo) expired. It only picks up again some two and half years later, with a visa issued this time by US authorities in Canada, and a fresh entry over the bridge from Windsor, Ontario to Detroit. It as if they hadn’t been living anywhere in between. But of course they had been – in New York City, that great chaotic anonymous metropolis and my eventual hometown.

My father was age ten to thirteen in those missing years. He learned his new language English quickly, as kids do. And he must have been instructed never to answer random questions from the police or others in uniform. Instructions he passed on to me, albeit now with constitutional footnotes.

What strikes me today, as our fourth amendment rights dissolve like wet slips of paper, is not just how they helped my family when it was otherwise defenseless from the state, but how they were designed to protect us all from the surveillance that now defines so much of our civic life. Tech companies have forged the way toward a voluntary surrender of our privacy, demanding “consent” for surveillance when we don’t have a choice. That surveillance has now been swept up by the state and directed against undocumented families like my own, as well as against those who are working to defend these families.

I am determined to continue in my insolence for this reason. I hope you might, too. We are going to need a lot of non-compliance to reestablish civil liberties, and safety from the state for ourselves and our neighbors.

Listening to: Whichever Way You Are Going, You Are Going Wrong (expanded edition) by Woo

Cooking: steam rice roll from the food cart at the corner of Hester and Elizabeth, NYC

Thanks for sharing our rights and good reasons from your life for knowing them.

thank you.