10.

It was on the same hallway as the Pacifist Bureau that K. discovered a unit with nothing inside but a safe. The safe was raised on cast iron wheels, a gesture more than a convenience as its weight made it impossible to move. Perhaps these wheels had once aligned with tracks, thought K., leaning against it and feeling the safe as heavy as a train car. But there were no tracks in the floors of the building, or signs of their removal, so how the safe had come to rest in this unit was a mystery. Unless, thought K., the building had been constructed around it - the safe being so immobile that the relative inconvenience of designing walls to fit was less onerous than constructing tracks to laboriously slide it elsewhere.

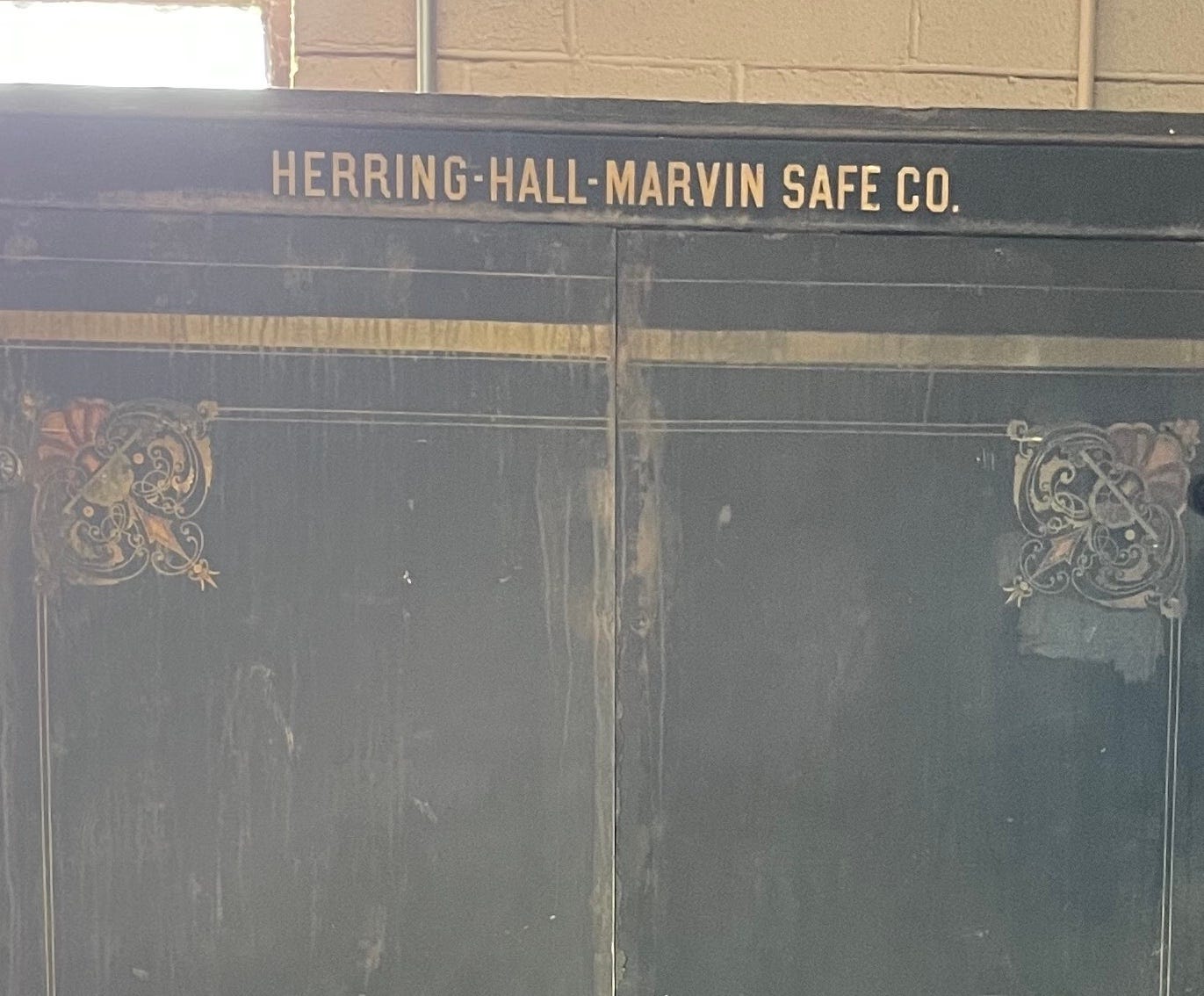

The safe had two doors to be opened in the middle like a wardrobe, with iron handles on each. A large dial with numbers made it clear that elaborate sliding locks must be fixed in place behind these doors. And yet in a fit of overcaution, or simply as a symbolic gesture toward the safe’s function, a chain had been placed around the door handles and fixed with a padlock. The padlock itself looked flimsy, thought K., especially compared with the massive construction of the safe itself – indeed, the lock looked identical to those on the outside of storage units, ones he routinely cut when necessary. In another, decreasingly intimidating measure, a rope had been fixed around the circumference of the safe. K. tried the knot and it came undone at the first tug, falling at his feet. Oversized hinges and decorative gold paint emphasized the scale and black finality of the steel. These doors would make a loud sound as they opened and closed. K. listened in the silence of the empty room.

If it were a wardrobe, thought K., the clothing stored in such a safe would be heavy as well – like those draperies and rugs he had seen in old paintings that didn’t seem to have any correlation to the flexible textiles encountered in life. These would be stiffly folded on solid shelves, most likely polished wood rather than steel in order not to harm the fabrics as they were removed. The decorative painting on the outside, K. now realized, was in fact made to look like carvings in wood. Perhaps this safe was a container built to hold one particular wardrobe, like those strong boxes made to protect a single delicate tea cup.

A trademark was painted in gold at the top, as if it were the name over a building’s entrance: “Herring - Hall - Marvin Safe Co.”

Herring Hall, thought K., does sound like a building – an inn by the sea, for example. And Marvin? The name seemed plain next to the grandiosity of steel and gold paint and luxurious fabrics carefully folded and stored behind locks. Although there might be a scent of sea in it.

Back with his research books, K. learned he was on the wrong track with “Mar–Vin.” The name is Celtic in origin, not Romance: originally Mervyn or Merfyn, the name of Welsh kings. A northern name, to go with “Herring Hall.”

This empty room with the safe held a special place in K.’s feeling for spaces in the storage facility. Like the “gallery” he created for the large paintings he found, it was neither precisely occupied nor abandoned. The room was not being used, that K. knew. But he felt equally sure that it was intended to be so again, despite the immobile wheels and silence of the safe’s locked doors. K. retied the rope.