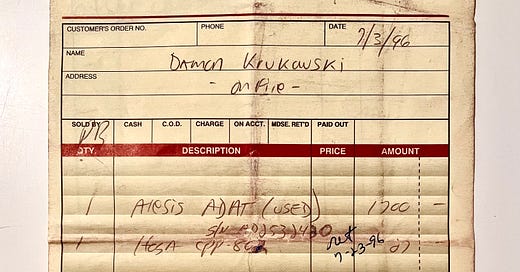

In 1996, we bought our first piece of digital recording equipment: an ADAT recorder. Eight tracks of 16-bit audio (CD quality!) recorded to… an S-VHS tape. The cheesiness of the tapes did not inspire confidence – you could find them at most any bodega, the same clunky plastic things used to tape movies off TV. But the machine was solid enough to take seriously, and actually seemed a bit of a miracle. It wasn’t cheap for us – new ones were out of reach ($3995), so we found one used. But that single purchase was pretty much all we needed to make our next album for Sub Pop, an unthinkable leap before digital made the “project studio” a possibility: recording equipment that didn’t have to be operating seven days a week to pay off. It could just sit there in our living room, waiting for us to have an idea…

I wasn’t aware of it at the time, but 1996 was also the year Bill Gates declared that in this new, digital world, “Content is King.”

“Content is where I expect much of the real money will be made on the Internet, just as it was in broadcasting. The television revolution that began half a century ago spawned a number of industries, including the manufacturing of TV sets, but the long-term winners were those who used the medium to deliver information and entertainment.”

With our ADAT, we felt self-sufficient because we could make an album on our own for the first time. But looking back, I think that was also the moment we became content providers. The digital medium was now installed in our house, and our job was to use it to deliver information and entertainment – just as Bill Gates recommended. How much content can two people generate, however? The first album we made in our project studio took us two years and came out in 1998. In 1999, Napster went live and you know the rest of the story: the major labels sued Napster to protect the value of their physical media, only to turn around and give Apple permission to sell digital downloads for 99 cents a track. Fast forward and our digital tracks are now valued at $0.0030 a stream by Spotify.

In other words, the twist to the plot of affordable digital technology was that it would fast devalue the results of our work, demanding that we make more and more content to try and keep up.

Gates seemed to see this coming, sort of:

“For the Internet to thrive, content providers must be paid for their work. The long-term prospects are good, but I expect a lot of disappointment in the short-term…’

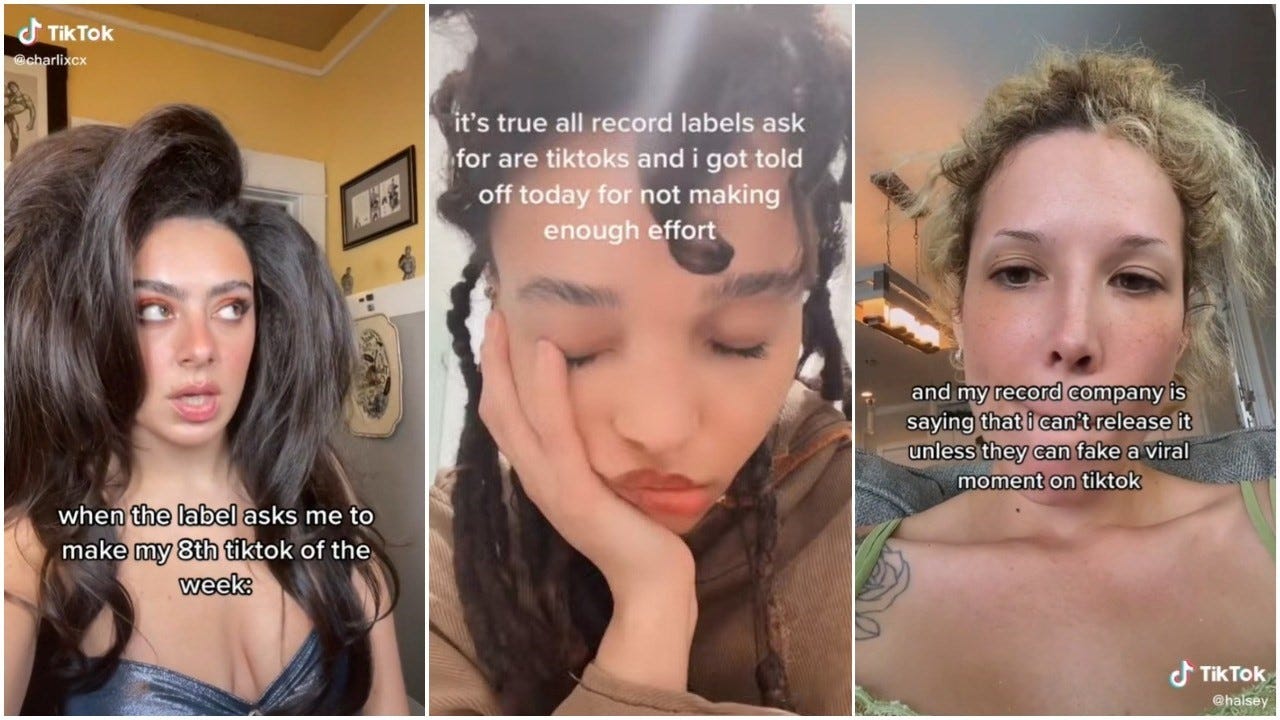

The problem is that the short-term, for musicians, has been around a long time. The entire digital age, to be exact. Content does not seem like it’s king to many artists like me; if anything, it feels a lot more peasant-y. Everyone makes content. And everyone has to make it all day long just to survive. Even pop stars have been complaining of late.

So what was Gates talking about? And why have people been repeating the phrase ever since?

For one, Bill Gates became extremely rich, as we all know – his own long-term was quite short. No peasant-y content production for him, or for all the other newly minted digital billionaires: “Those who succeed will propel the Internet forward as a marketplace of ideas, experiences, and products - a marketplace of content,” Gates gloated in his summation.

Notice that marketplace is slipped in that concluding phrase, close by but distinct from content. When Gates says content is king, he is not talking from the point of view of a content provider – the laborer tied to the ADAT for whom the short-term, remember, will be filled with “a lot of disappointment.” He is speaking from the castle where the winners live – “those who use the medium to deliver information and entertainment.” Deliver, not create. Gates was talking about becoming a king by owning the marketplace, not the content itself.

My labor as a content provider is not at all what Gates had in mind. He didn’t have any labor in mind. He was talking as a capitalist – owner of the network, to use his broadcast analogy. It’s just that the network in this case (the internet) was publicly owned, so he had to invent a way to privatize and profit from that shared technology.

So what of the content providers? When will our long-term kick in?

1996 was also the year that Marxist philosopher Maurizio Lazzarato published the essay, “Immaterial Labor.” I can’t say I understand everything Lazzarato meant by the term, but I think I get the basic idea because I have been practicing it for twenty-five years. Immaterial labor describes the condition that the ADAT introduced into my work life. What seems like autonomy is, in Lazzarato’s analysis, an adaptation of capital for control of the worker in the postindustrial economy.

“First and foremost, we have here a discourse that is authoritarian: one has to express oneself, one has to speak, communicate, cooperate, and so forth… Capital wants a situation where command resides within the subject him- or herself, and within the communicative process. The worker is to be responsible for his or her own control and motivation within the work group without a foreman needing to intervene.”

Our project studio - no longer ADAT, those S-VHS tapes were doomed to obsolescence - is in Lazzarato’s description like having a foreman live with us. Digital technology gave us tools to work on our own, but that satisfies a very useful adaptation for capital to profit continually from our labor. Perversely, the flexibility of digital recording equipment leads to the unstable conditions we now experience as content providers.

“Small and sometimes very small ‘productive units’ (often consisting of only one individual) are organized for specific ad hoc projects, and may exist only for the duration of those particular jobs… Precariousness, hyperexploitation, mobility, and hierarchy are the most obvious characteristics of metropolitan immaterial labor. Behind the label of the independent ‘self-employed’ worker, what we actually find is an intellectual proletarian… It is worth noting that in this kind of working existence it becomes increasingly difficult to distinguish leisure time from work time. In a sense, life becomes inseparable from work.”

This matches my long-term experience with digital media far better than Gates’s “content is king.” Content is not what is rewarded in this online economy, because content is produced by immaterial labor, and labor is in no better a political state to demand fair compensation now than it was before digital technology. If anything, our ability to organize has been reduced as we have been isolated by the processes described in Lazzarato’s essay. After all, the foreman is always right here with us. I’m typing on one now.

Listening to: Trust in the Lifeforce of the Mystery, by The Comet is Coming

Cooking: garlic scapes, in everything

Nodding so hard in agreement that my head might come loose off my neck.

It is a low down dirty shame that music, one of the most enjoyable experiences in life, has been reduced to marketplace content. It is down right insulting what artists like you get from streaming services. Thankfully I have enough LP's cd's and digital files that I do not have to subscribe to any streaming services.