Like many in the wake of Twitter’s sale, I’ve been exploring a decentralized, non-profit alternative called Mastodon, part of an open-source collection of social media sites called the “Fediverse.” And coming from Twitter, the general tone of posts on Mastodon is strikingly positive - open, curious, declarative rather than combative, searching for community rather than representing. None of us new arrivals know the folkways of the platform, so none have come prepared to work it. For now at least, it seems we’re all listening. Shouting feels outré.

This quiet curiosity is to me a throwback to earlier web environments, and I’ve been thinking about my first days online. I think many of us are - although the speed of internet growth means those first days vary widely according to age. Online generations are sliced extremely thin.

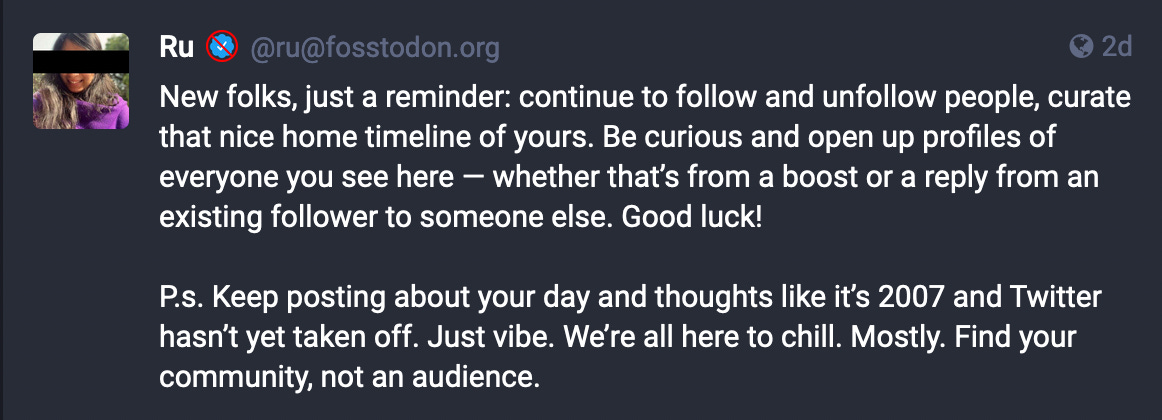

Journalist Taylor Lorenz, energetically exploring Mastodon in her professional way, said it gave her “2013 Twitter vibes.” A more experienced Fediverse user named Ru advised newcomers to “Keep posting about your day and thoughts like it’s 2007 and Twitter hasn’t yet taken off.” “Find your community,” she added sagely, “not an audience.”

Other users – likely older - seem to have been thrown even further back into internet history. I’ve seen numerous nostalgic references to Usenet, the forums which became widely popular in the 90s, and were themselves based on earlier forms of exchange between those with university or government access to the pre-World Wide Web internet.

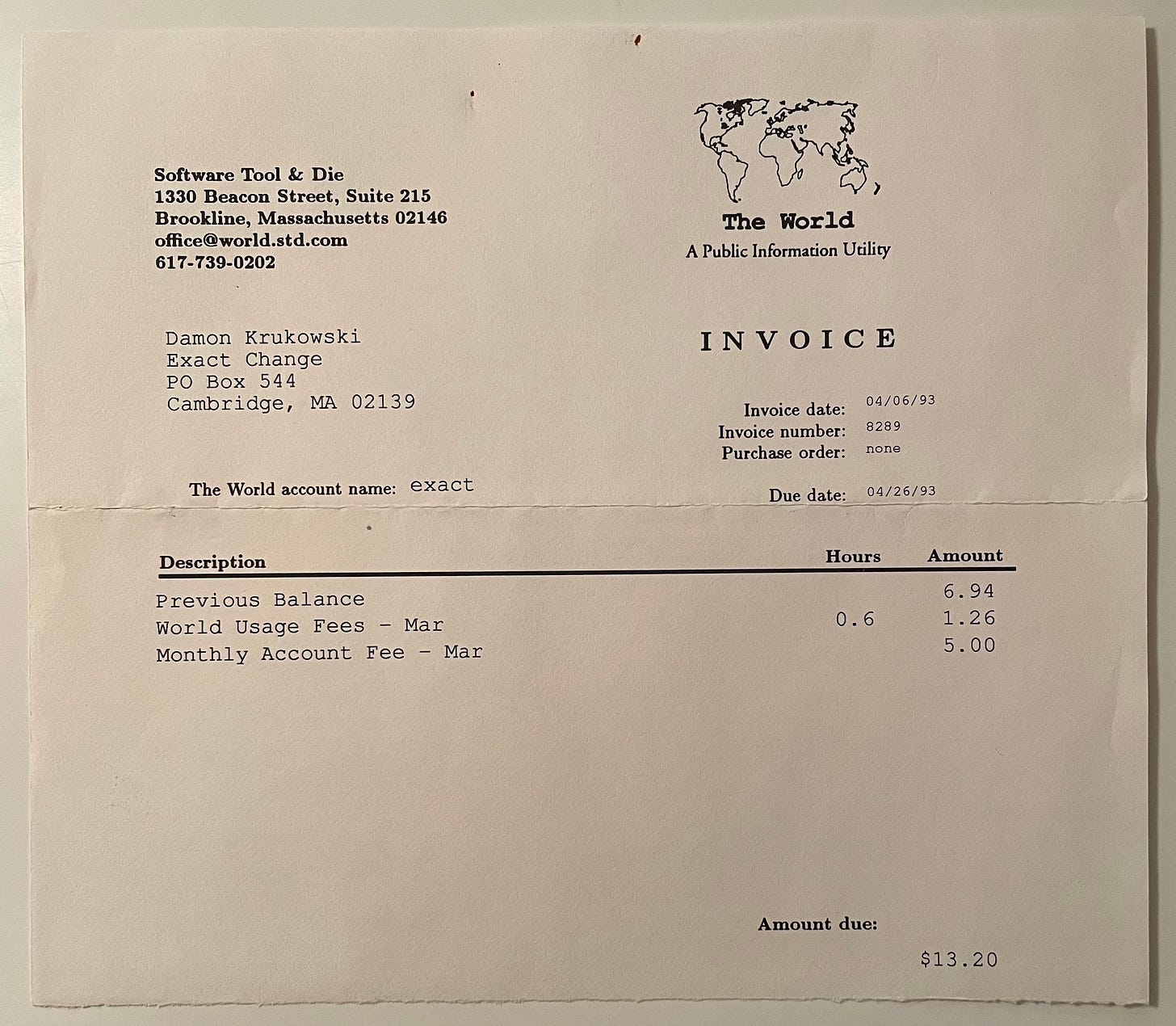

My online memories begin in 1993, with an account for email and web access via The World, a Boston-based provider that was simply our local but turns out to have been, according to Wired, “the first commercial dialup ISP.”

When I think back to those first internet explorations of my own, I mostly remember confusion, and not a little boredom. The purpose of email was immediately obvious, because it functioned by analogy to the post office and was something we already needed for our work. But what was this “web” for, I recall thinking. There were few sites to visit, and it was hard to learn where they were located (search engines were far off in the near future). Naomi and I poked around on our one computer, struggling to find much of anything interesting or useful on the internet.

That changed.

“What was great about the ’50s,” wrote composer Morton Feldman, looking back from the vantage point of 1971, “is that for one brief moment – maybe, say, six weeks – nobody understood art. That’s why it all happened. Because for a short while, these people were left alone. Six weeks is all it takes to get started.” (from Give My Regards to Eighth Street)

If you’ve ever had the good fortune to find yourself in a scrappy, energetic, probably mostly broke scene of strange new creative work, you might recognize what Feldman was describing. I imagine that’s what some computer pioneers experienced in the 70s. For me, the mid-80s US music scene that came to be known as “college rock” (and later “indie” or “alternative”) was like that – there were certainly six weeks in there where nobody understood rock bands. And more than a short while when most everyone left us alone.

Some aspects of that kind of “garage” period – disorganized to the point of aimless, decentralized to the point of isolated – might sound unpleasant. Maybe they are for many. But they can be accompanied by flashes of discovery, camaraderie, invention… everything that Feldman describes rhapsodically about the six weeks of confusion in New York of the 1950s:

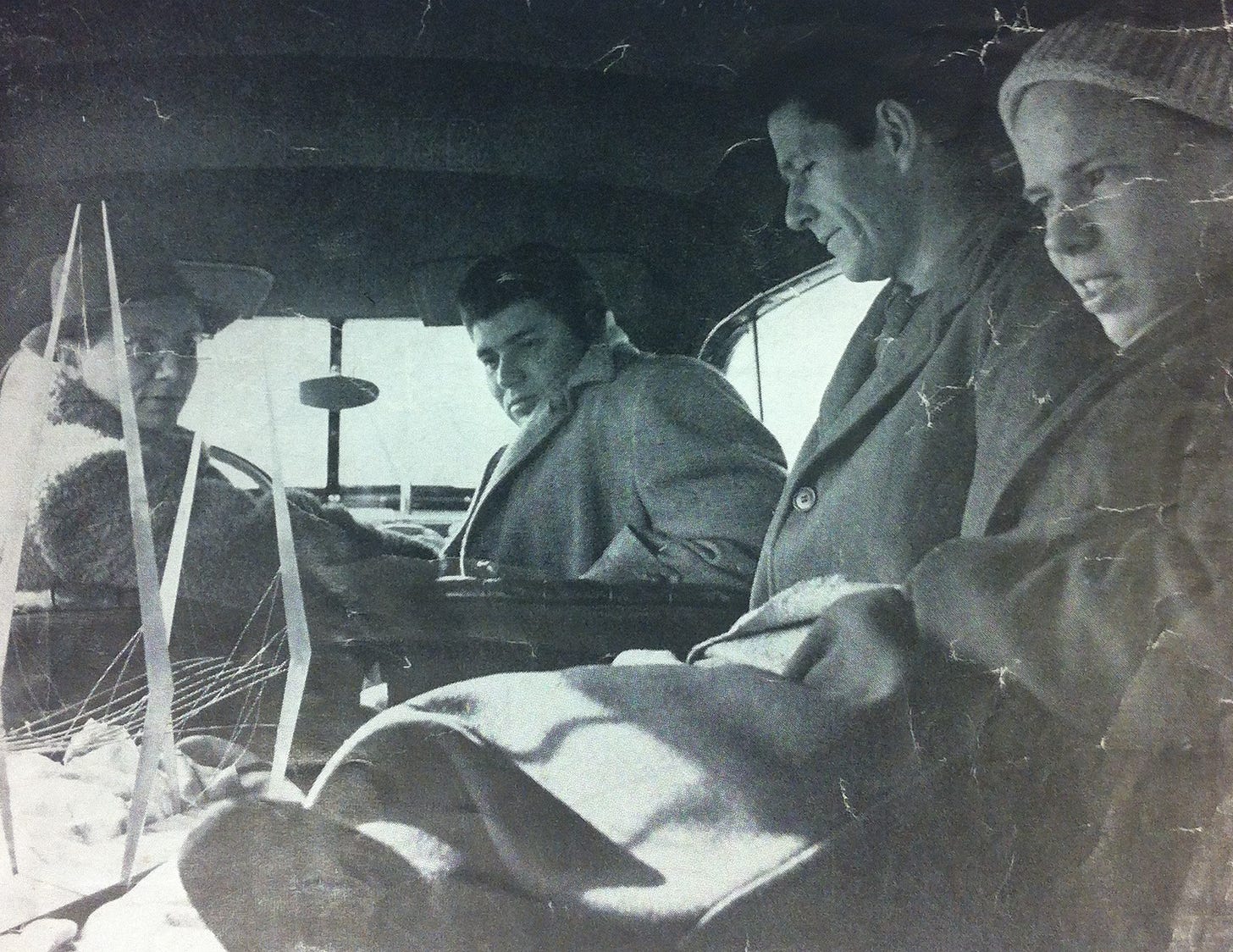

“One day there was a knock at my door. It was John [Cage]. ‘I’m going over to see a young painter called Robert Rauschenberg. He’s marvelous, and his work is marvelous. You must meet him.’ Five minutes later we were in John’s Model A Ford, on the way to Rauschenberg’s studio on Fulton Street. Rauschenberg was working on a series of black paintings. There was one big canvas I couldn’t stop looking at.

‘Why don’t you buy it,’ Rauschenberg said.

‘What do you want for it?’

‘Whatever you’ve got in your pocket.’

I had sixteen dollars and some change, which he gleefully accepted. We immediately put the painting on top of the Model A, went back… and hung it on the wall. That was how I acquired my first painting.”

This kind of anarchic six weeks quickly evaporates, along with $16 Rauschenberg canvases. Which is Feldman’s larger point. “Now, almost twenty years later,” he writes, “as I see what happens to work, I ask myself more and more why everybody knows so much about art.”

“Thousands of people – teachers, students, collectors, critics – everybody knows everything. To me it seems as though the artist is fighting a heavy sea in a rowboat, while alongside him a pleasure liner takes all these people to the same place. Every graduate student today knows exactly what degree of ‘angst’ belongs in a de Kooning, can point out disapprovingly just where he has let up, relaxed. Everybody knows that one Bette Davis movie where she went out of style. It’s another bullring, with everybody knowing the rules of the game.”

Rules of the game… What Feldman saw around him in 1971 was a much more centralized art world, with judgements passed quickly in a society unified by mutual investments of social and financial capital. (Of course others – those excluded from that society – were having their own six weeks of confusion in early 70s New York, likely unbeknownst to Feldman.)

Online life has become even more centralized and unified than the art world Feldman pictured as a luxury liner carrying everyone to the same conclusions. The massive social media platforms, with their massive (over-) valuations, are pleasure/pain liners on a larger scale than anything Feldman could have experienced. But just like the conventional art world that he railed against, they are aimed above all at establishing norms and eliminating confusion.

No wonder so many comfortable with current social media paradigms seem to bristle at the experience of Mastodon and the Fediverse (their complaints are, naturally, trending on Twitter). Its decentralization is intended to thwart the dazzling numbers of centralization. And its non-profit, ad-free structure is intended to prevent turning users into passive consumers of information fed them by the platform. It is, in short, designed for confusion. Just like a lot of music and art.

Listening to: Voices of Bishara by Tom Skinner

Cooking: the last green tomatoes on the vine, sauteed with garlic and capers into a bitter-tart sauce

I'm inclined to think that there's always someone having their "six weeks" somewhere.

I certainly enjoyed my time in college in the early 80s, being in underground ("post punk" as we know it now, or "new wave" or artsy punk) bands when nobody besides those of us involved in it cared much about it. Nobody knew what we were doing (including us, I guess) so we were free to keep making it up as we went along. I still feel like that's almost always the best way to do anything creative.