The Problem with Live Music

There’s a problem with live music.

The immediate, obvious part of the problem is COVID. Disruptions to travel, barriers at border crossings, limitations on indoor gatherings, risks for crowds of any kind are threats to live music as we know it. People have built innumerable spaces for live music around the world, all of which are designed to bring human beings into close contact with one another. Live music simply doesn’t happen without the situation that COVID has made precarious. We make sound by vibrating air; an airborne disease infects every aspect of music making.

But there’s another, more longstanding problem with live music – its increasing reliance on larger and larger shows, and dominance by a very short list of corporations who produce nearly all of them. According to the LA Times, “Of the nearly $22 billion in ticket revenue sold globally for live music events in 2019, Live Nation promoted about 60% of those shows, AEG handled roughly 30% and the other 10% were organized by indie promotion firms.” 90% of an industry controlled by only two players is a big problem.

It might seem that these issues – COVID and corporate consolidation - are unrelated. Personal experience makes me not so sure, however.

Last month, the Washington Post published an investigative report about a possible origin for COVID-19, pinpointing bats living in a network of caves near the city of Lichuan, prefecture of Enshi, province of Hubei, China. The largest of these caves is called Tenglong.

“The Washington Post made a rare trip in September to Enshi, six hours' drive west of Wuhan, where the coronavirus was first detected. A reporter observed human traffic into Enshi caves, including domestic tourism, spelunking and villagers replacing a drinking water pump inside a cave. Defunct wildlife farms sat as close as one mile from the entrances… Scientists briefed on The Post's reporting said it documents a plausible pathway for how a coronavirus could have spread from bats to other animals, then to Wuhan's markets.”

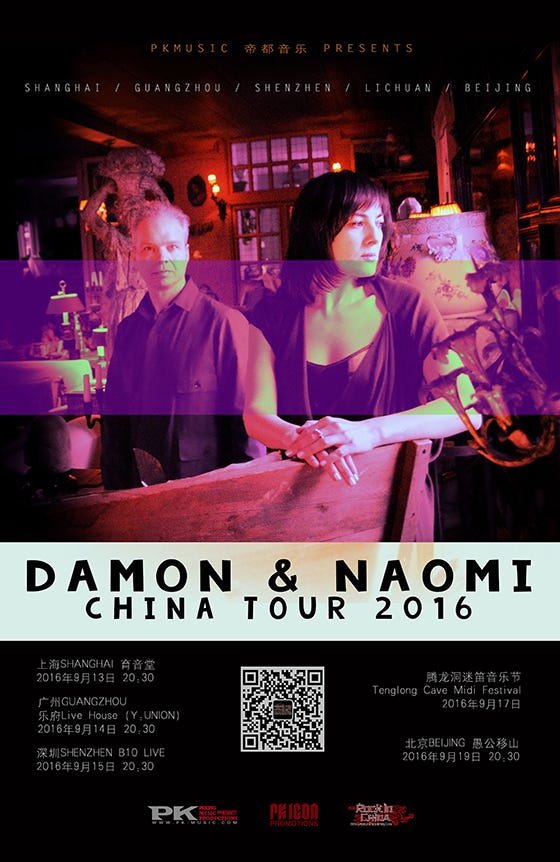

Naomi and I were probably less impressed than others by the Post reporter’s epic journey to Tenglong, because we played a show in that very same cave, September 2016. I bet the reporter didn’t have to carry as much equipment there as we did!

Why we played a show in such a remote corner of the Chinese provinces, why we played it in a cave, and how we could have become patient zero and one for a global pandemic are I believe all aspects of the problem with live music we are facing today – tied up into one dense knot.

Our tour of China in 2016 was to four major cities – Shanghai, Guanzhou, Shenzhen, Beijing – and one outpost so remote the Washington Post could brag about simply managing to get a reporter there. Why travel so far into the provinces for one show? Because it paid for all the others, of course. That is how touring in recent years has worked for so many artists, in so many places around the world. You find a festival booking, and the fee from that appearance underwrites the rest of the venture. Find a bunch of festivals that you string together, and you might even come home with a profit.

This push toward festivals has come from capital consolidation. Festivals like those promoted by Live Nation and AEG – or Midi in China, which promoted the Tenglong Cave festival – depend on gathering the largest possible audience in one space. Crowds of 100,000 change the economic profile of live music, moving it away from the simple counting of fannies in seats and toward revenue produced by “dynamically-priced” and “fee-bearing tickets,” “per-fan spending” on site, “high-margin sponsorship” and “brand partnership,” to quote terms used in Live Nation’s 2019 financial report to investors. Here is how Michael Rapino, President and CEO of Live Nation, summed up that report, looking ahead to a pre-pandemic 2020:

“In summary, 2019 was another strong year for Live Nation – building our global concerts business and driving growth in our high-margin venue, sponsorship and ticketing businesses. Looking at 2020, we believe that our double-digit fan and show count growth so far this year against a backdrop of very high artist activity across all venue types and markets sets up our flywheel to deliver another year of strong global growth.”

There is no mention of music in Rapino’s summary – Live Nation is in the “venue, sponsorship and ticketing” business. “Artist activity” is just a “backdrop” for what they truly have in the spotlight: “strong global growth.” You can’t generate these kinds of income from a regular venue for live music – they are the creations of a festival economy that follows its own logic, built for scale of audience and independent of any particular music.

Which is how we ended up playing in a cave.

When we finally arrived for our soundcheck at Tenglong it was night, at the close of the first day for the festival. The entrance to the cave is massive, big enough that tourist brochures picture a helicopter flying inside it. But our stage was a kilometer inside the cave, so far there was a small railway to ferry us. The crew, who had been there all day, looked pale and exhausted. And they were all coughing: hacking, hoarse coughs in the damp, heavy air of the cave. No Smoking signs were posted everywhere, and everyone was smoking.

We soundchecked as fast as we could, and raced back out toward the starlight. We were deep in the countryside – we had to walk single file across an undulating suspension bridge over a river to reach the festival site from the road.

Next day, the festival was jammed with people. The main stage was at the mouth of the cave, so we had to push our way through the crowd to reach the mini-railway inside that took us to the second stage, where – although it was now a bright sunny autumn day – it was as cold and damp and dark as it had been the night before. The staff were all still coughing. I dropped my gear backstage and spent a half hour working my way back out of the cave to daylight, determined to breathe as much as possible before our set time.

The show itself was remarkable mostly for the natural reverb, longer than any setting on any digital box I’ve ever used. We slowed our songs down (even further!), and let our voices mix in the echo. It felt a bit like singing in a stone church, if the church was filled with stale air and bats. Definitely our most goth gig, ever.

Outside in the night, after the show, there were roadside stands cooking food on open fires just past the undulating bridge. We got back in the van.

*

How could this most unusual show be typical of touring?

Festivals, no matter how exotic the locale, resemble one another more than not. Every small venue we played in China was distinct in its local ways – the audiences had different concerns, received our show in a different manner, taught us different things about their cities, their favorite bands, their local foods.

At Tenglong Cave, we were one of dozens of bands playing to a sea of faces we never met. Backstage, we spoke to some of the other musicians who had also traveled from far away, and to the promoters – who had come there from Beijing. And then we left.

The only thing we might have taken away, as I now know, was a virus.

Festivals are designed this way, sequestering the artists and the promoters in a No Access area that might as well be a cave, even if it isn’t actually a kilometer inside one. There’s a protective barrier between you and the audience. Out there, a mass of merch- and food- and water-buying people with fee-bearing, dynamically priced tickets are soaking up high-margin sponsorships and branding. Deep inside the cave, the promoters and artists are in another world. It’s not about sharing a space with an audience.

I am grateful to Midi for bringing us to China in 2016 - it was a powerful experience for me and possibly even more for Naomi. And I know that our tour as a whole, with its many unforgettable moments for us, was financially feasible only because of the Tenglong Cave festival. But the festival itself, like so many festivals in so many places around the globe, was a disaster waiting to happen. At the time, I thought about the pitch black in that cave if the power went out. I thought about tens of thousands of people trying to cross that undulating bridge, single file, in an emergency. And little did I know there might even be the source of a global pandemic involved.

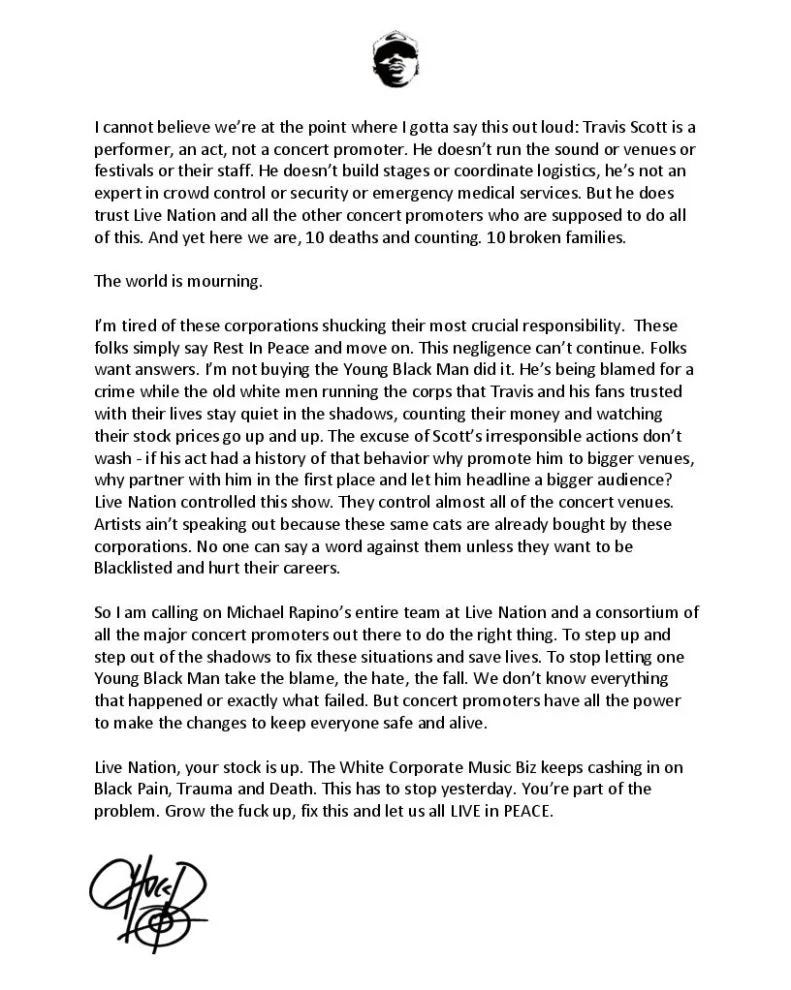

These are things artists can’t or won’t say, even if they think them, because festivals have become so crucial to the economics of live music. All the more reason I am – yet again – wowed by Chuck D, who wrote an open letter about the recent disaster at the Houston festival Astroworld, and didn’t hesitate to lay blame where blame is truly due.

I hope Live Nation listens to Chuck D. But corporations in such dominant positions of power over their market, like Live Nation, don’t seem to listen to anyone other than investors. As Chuck D says, Live Nation “control almost all of the concert venues.” If artists have a problem, where else can they go? And really, it’s the same for consumers – many don’t have access to live music except through mass events like Astroworld, because the largest promoters drive their competition out of business.

COVID will likely only accelerate this consolidation in live music, as independent venues fail to weather a year or more without audiences. Live Nation and AEG have the capital to wait this out, and emerge with an even greater market share.

Consolidation is all about eliminating choice. And when we have no choice, as artists or consumers, we might well end up in a dangerous situation like Astroworld, or for that matter a cave in China which could be the source of a killer virus - simply because we want to play, or see, a show.

That’s the problem with live music. And I don’t expect those who got us into this, to lead us out. COVID has decimated so much of our industry. But where will new ideas about how to share live music emerge - now that bringing people close together is itself problematic - if no one is still in this business except Live Nation and AEG?

Listening to: Faust, punkt

Cooking: Leftovers