The Red Herring of Intellectual Property

There’s a concept in European law that is more or less foreign to the US legal system, called “the moral right of the artist.” The idea is there are certain aspects of copyright which cannot be signed away – they attach to the work and its creator, regardless.

In the US, copyright is seen as an economic issue only. Like any other aspect of property, it can be sold, reassigned, given away. “Intellectual property” is, in this regard, nothing special. But for the artist, it can seem like a source of power and wealth – it’s property, after all. And it’s conjured up out of nothing but ideas.

This endless fount of property is like the original sin of art in America. When you start to create, you start to generate property. Exciting, no? But also – in my experience, from the very beginning of my career in recorded music – problematic.

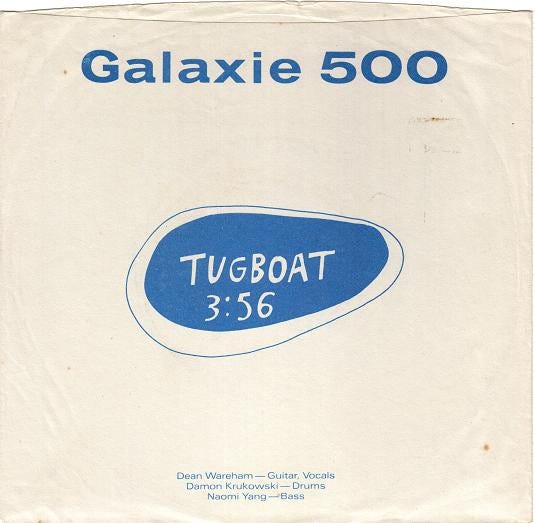

The first thing Galaxie 500 did - aside from being friends, forming a band, and starting to write songs together – was negotiate intellectual property rights. We signed a homemade “contract” with an equally young guy in Boston to put out our first single, Tugboat b/w King of Spain. This was going to pay for his future children’s braces, he said, with a strange gleam in his eyes. And then, after the initial copies sold, he refused to repress, because the singles he saved for himself would be more valuable as collector’s items if he didn’t. Our first and only recording was unavailable almost as soon as it had launched.

What I learned that quick was we could lose our intellectual property (the rights to our recordings) simply by signing a piece of paper.

Of course the paper could have all kinds of clauses in it, protecting our rights under various conditions. So the next contract we signed – with the same guy! (fool me twice, shame on me) – gave away our first album, but this time with language assuring that it would come back to us if… and if… and if…

Ever try and prove a clause like that in a contract has been triggered, and the contract negated? You’ll need a lawyer to do it. And lawyers cost money.

Lesson two: our protections on paper were only as good as the lawyer we could afford to enforce them. We had signed away our intellectual property, but needed actual cash to get it back. How to get that cash?

Sign another contract – with a bigger label, and with many more clauses in it.

Lesson three: when the bigger label that gave you an advance with which you paid a lawyer to rescue you from your prior contract later declares bankruptcy, you’re going to need another lawyer (music lawyers don’t do bankruptcy) to try and get your rights back from the auction being held to liquidate that label’s assets, which now include your intellectual property.

I felt much older but was still in my twenties when I went into that bankruptcy auction, with nothing but amateur documents I prepared myself (Galaxie 500 had since broken up so there was no yet-bigger advance to pay for yet another lawyer to get us out of this fresh mess). My goal was to try and extricate our intellectual property and return it to our collective possession.

Happy to report we won. But what it took was renouncing any and all royalties we were owed from our contracts to that date.

Lesson four: any money we earned while in Galaxie 500 was not from our intellectual property – we never received any of the royalties promised in our original contracts. And yet, we had earned money – a living, even - while working in that band. What from?

Now we’re on the scent of the real thing, no red herring of intellectual property transferred by a signature dragged across paper.

If you follow the money we actually earned while in Galaxie 500, we were paid for our labor. For our labor at shows, paid at the end of each night. And for our labor writing and recording songs, paid out of a budget given us to do that work (the rest went to our producer and his studio).

There’s nothing about intellectual property in those exchanges. Do this, and get paid X for it. Have someone else do work for you, and pay them X for it. These are the same as payments for labor in any job.

So why all the hullabaloo around those contracts we signed, which ended up negated anyway? We had been told it was our intellectual property that gave us earning power in music. But in fact, it seems we had been selling our labor all along.

In the US, you can’t sign away your labor, legally. That’s indentured servitude.

But you can sign away your intellectual property. That’s the music business.

I’m going on about these old hard lessons I learned in my twenties, because here I am decades later still trying to establish minimum fair pay for my work in music. And when I push for it, what I often get back are arguments about intellectual property – just like I did then.

There are certainly very important conversations to be had about copyright in music – copyright can offer protections for our work as creators, although like any other contract those protections typically require capital to enforce through civil legal action.

But intellectual property is not the same as labor, and discussions about the protection of copyright shouldn’t take place at the expense of conversations about the protection of labor in music. Yet it seems to me that is exactly what happens, all too often.

Streaming makes this situation more extreme, like so many aspects of virtual life. The streaming platforms pay the rights holders for use of recordings – that is, they pay whoever the musician signed a contract with for their intellectual property. Whether any of that money ever reaches the musician is not the responsibility of the platform – they are only making use of intellectual property within the realm of current copyright law.

So if the musician who makes the recording that is now streaming earns as little as $0.003 per stream, or even less, or even nothing…? It’s a question of intellectual property, not labor.

You see how this works.

What if we reframe the economic problems we face now as musicians, and view them more simply as a question of fair pay for our labor, rather than a question of intellectual property rights?

I believe the solutions to those problems then become simpler as well. As simple, and as protected by the state, as labor is in other jobs. We make recordings, we should at minimum be paid fairly for use of that work. And that’s something which can’t be signed away, because it’s about our labor not our intellectual property.

I wouldn’t advocate for the elimination of copyright, it has a crucial role to play for creators. But as a musician, my experience tells me not to count on it for making a living. My work is labor like anyone else’s.

Listening to: jamie branch, Fly or Die II: bird dogs of paradise

Cooking: verjus, from crushed sour grapes

Hey Damon,

I hear you! Love your work.

I just wrote something that might interest you. As a new (old) writer, I would welcome your thoughts.

Best wishes, David

https://blog.openmusic.io/the-openmusic-project/

Do you think this is a problem for all creative industries? It seems like the model is similar in the publishing industry as well. How do you think creators could go about demanding fair wages for our labor?