The music industry has expended a lot of effort insisting what streams are not.

TikTok videos with music soundtracks are decidedly not a synchronization – if they were, they would be subject to individual negotiation and payment for their use of music, like commercials or films. Even music videos for cover songs have to seek permission from the original songwriters to link their music to moving images.

Instead, as Music Business Worldwide explained in a recent article, TikTok isn’t accounting for individual streams of music at all – they are negotiating blanket licenses for unlimited use with single payments to the major labels, unconnected to individual works. “Once these so-called ‘buy-out’ checks have been banked, it grants TikTok a free license to use these music companies’ music for the duration of whatever the agreed period is,” explain MBW’s sources.

But streams are also not a license, as Domino Records’ lawyers argued against a suit brought by Four Tet – after all, if they were a license, any income they generated would be subject to the usual 50/50 split with artists guaranteed by record label contracts. Instead, Domino maintained – for themselves but really for all their label colleagues - that streaming should be accounted for like a physical sale, or at best a digital download. Which sounds generous, except physical sales give the artist a 12% or so share of the proceeds, and downloads usually only a bit more (Four Tet’s rate for downloads from Domino was 18%).

Yet streams are not a sale, neither like physical media nor like a digital download, say the record labels out the other side of their mouths, because if they were then each song streamed would be subject to the statutory mechanical royalty due to songwriters for sales of tracks – 9.1 cents a pop… Anyway, isn’t streaming more ephemeral than a sale, like a public broadcast on the radio?

Hang on, says Spotify, streams are not a public broadcast, because if they were, then they would be subject to the many regulations radio has acquired over the decades. For example, taking payments for better algorithmic placement in streaming would, were it on the radio, be payola – and payola is illegal, while Spotify pursues this kind of bribe as a normal marketing program. No, streaming is obviously not radio – after all, it’s entirely different because it is digital…

Like satellite radio, you mean…? NO, it’s not satellite radio, say all the streaming platforms together in a very loud voice. Because if streaming were satellite radio, it would be subject to the statutory royalties established for digital broadcast by Congress in the 1990s, which are collected by SoundExchange. No, those digital services like SiriusXM are “noninteractive,” insist the platforms – unlike streaming, which is “interactive.”

SoundExchange provides a helpful FAQ to determine if your particular digital music service is noninteractive and therefore subject to statutory royalties:

How do I know if my service is “noninteractive?”

Noninteractive services are very generally defined as those in which the user experience mimics a radio broadcast. That is, the users may not choose the specific track or artist they wish to hear, but are provided a pre-programmed or semi-random combination of tracks, the specific selection and order of which remain unknown to the listener.

Which sounds an awful lot like algorithmic playlists on streaming platforms… many of which are even referred to as “radio.” But evidently, they are not.

So what is streaming, anyway?

If you listen to the powers that be in the music industry, streaming may well be nothing at all - at least nothing that concerns you, the musician. Just be glad these platforms are not pirates!

Not pirates, you say…?

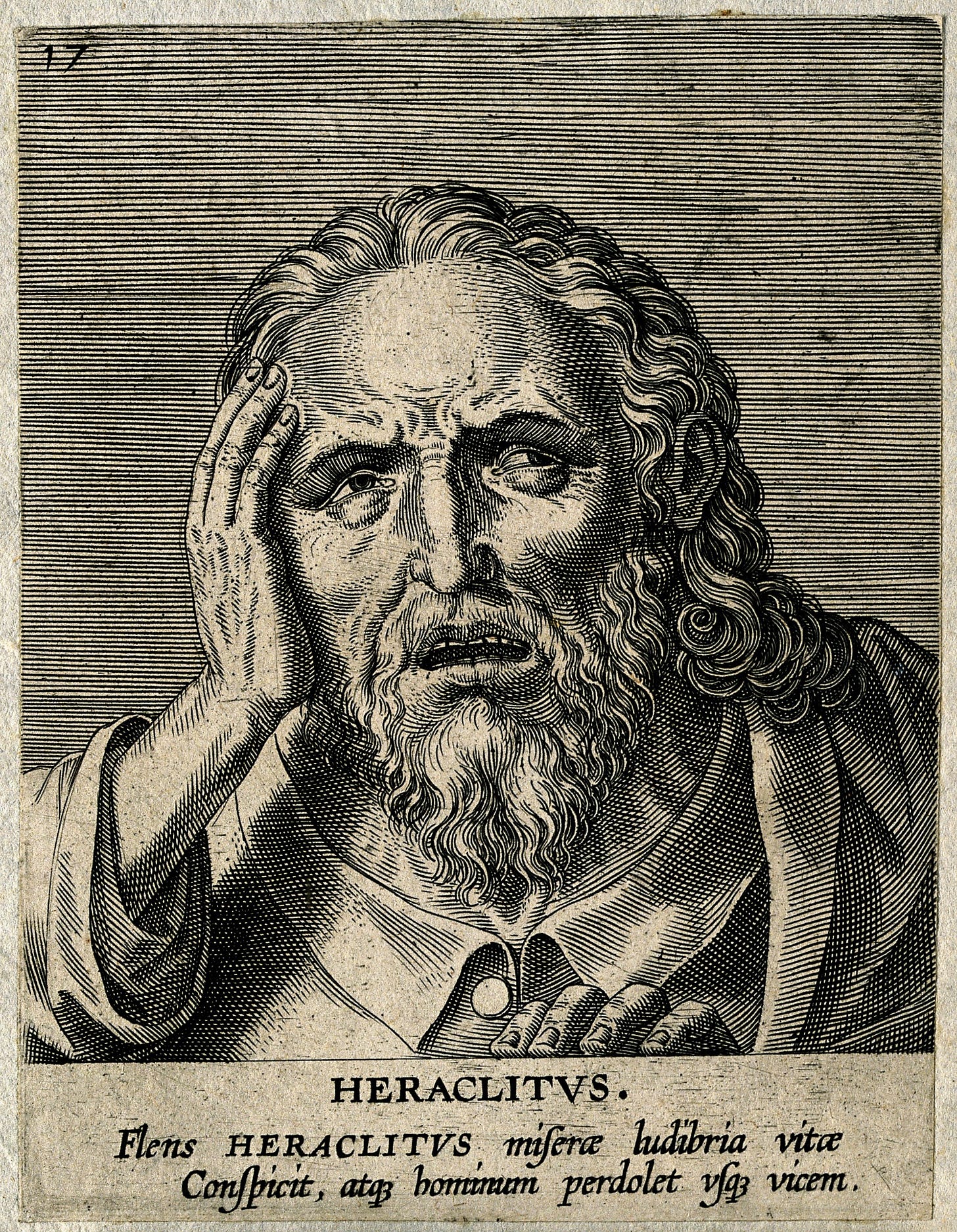

Let’s puzzle this out from what we know of the world, like a pre-Socratic philosopher:

It’s self-evident that streaming exists.

It must therefore be something, as well as not being many other things.

We know all the things it is not – many things which, it so happens, are subject to existing laws and regulations for payments to musicians for use of their work.

If streaming is indeed none of these things, it must be a new category of use for music, made possible by a new technology. Just like records made mechanical reproduction possible. And film made synch possible. And radio made public broadcast possible. And satellite radio made digital public broadcast possible.

If it is a new category of use made possible by a new technology, it is in fact just like all those prior ones. And therefore in need of new laws and regulations insuring a standard of payment to musicians for use of their work.

Logic tells us: we need a new streaming royalty for this new technology

After all, as the industry has so eagerly explained, none of the old ones apply.

Listening to: $1.78 million dollar bash

Cooking: Drained yogurt with salt

Another delicious post which leaves a bad taste in the mouth. The Guardian did a good job coming to the nub of the problem on the slightly unrelated topic of dynamic ticket pricing.

“Music streaming services such as Spotify have all but destroyed artists’ ability to earn money through album sales. That means country-hopping tours have become a much more important revenue stream. In that sense, an Oasis fan who streams Don’t Look Back in Anger without paying for it is partly complicit in the eye-watering mark-up they might be charged to see the Gallagher brothers actually perform it.”

https://substack.com/@simonjcampbell/note/c-67506357

Everything that Spotify (and similar) does is solely in service of the listener, which by design makes this near-impossible to fight. People LOVE it… and when I explain the artist’s perspective, even the genuinely sympathetic don’t change their listening behavior.