Zeitgeist

The Sound of 1991

There’s been a lot of talk about 1991 in the music community, with the 30th anniversary of the release of Nirvana’s commercial breakthrough Nevermind. A number one album is nothing if not zeitgeisty. But maybe not only for musical reasons? On the other hand, I was struck by the deep familiarity to me – nostalgia, really – of simply the sounds in this 1991 documentary about improvised music, which aired at the same moment Nirvana was on top of the charts but I’d never seen till now:

Of course there’s always an alternate cultural history told by the avant-garde; but that’s not exactly what’s going on in this four-part series by director Jeremy Marre. The first episode features a grade school class in Chicago taught by jazz musician Douglas R. Ewart; an Early Music performance of Mozart by the Academy of Ancient Music in London; John Zorn rehearsing his composition Cobra in New York; the organist at Sacré Coeur in Paris, Naji Hakim; Gaelic psalm singing in the Scottish Hebrides; and the Mishra family of musicians in Varanasi (Banaras), on the Ganges River.

Given my own musical career path up to 1991, little of that should have been familiar to me – yet it all was, more or less. Galaxie 500’s producer Kramer had put out the first recording of Zorn’s band Naked City on his label Shimmy Disc in 1990. The Boston Early Music Festival brought its leading practitioners to our adopted city, and in 1991 featured period instrument performances of Mozart in particular (it was the 200th anniversary of his death). In college, my work-study “job” had been a paid chorister at Harvard’s Memorial Church under the direction of organist John Ferris, who would delight us at the end of services with extended solo improvisations. And Naomi’s and my early CD collection was filled with “sacred” and “world” music very much connected to what is chronicled by the documentary – with an emphasis on the subcontinent. (Our 1992 debut as a duo, More Sad Hits, lifted its title from a CD compilation of Indian music. It also made use of a sample from a Mozart opera – listen to the second half of the track, “Astrafiammante.”)

Meanwhile, I never even got to see Nirvana, partly cause in the early days we were both touring the same venues - Galaxie 500 and Straightjacket Fits were about a week behind Nirvana and TAD on a nearly identical tour of Europe, November 1989 (we knew, cause the hotels we were supposed to stay in kept cancelling after TAD’s visit).

All of which makes me wonder about musical zeitgeist, and how we might mistakenly historicize it. The improvisatory music in the documentary On the Edge doesn’t date to 1991, the same way Nirvana (and Galaxie 500) do – some of it is even hundreds, possibly thousands of years old. Yet it was very much in the air that year. Literally. I heard it in the air of performance halls and churches, and coming off our living room stereo speakers.

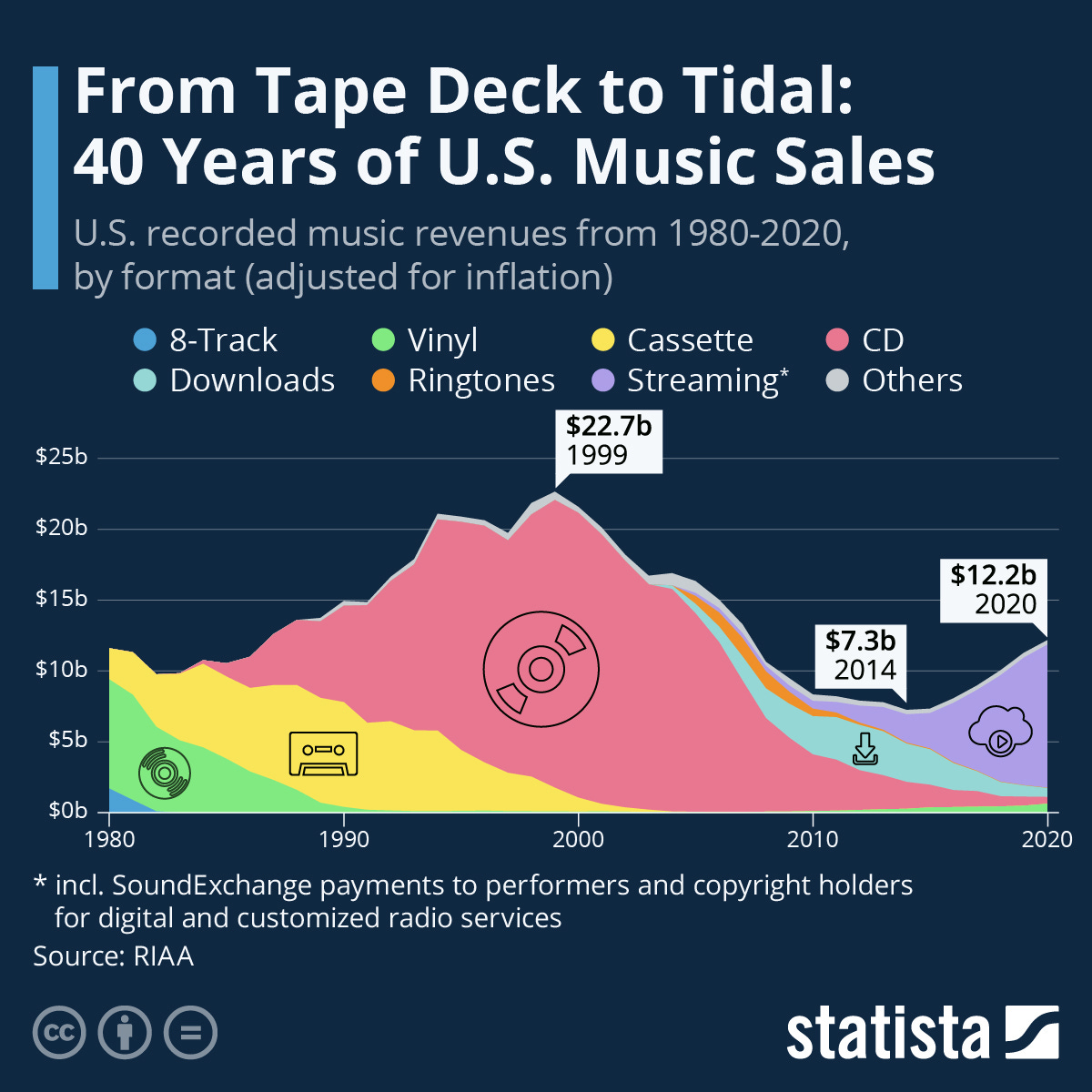

One reason for that timing may have been a rather sudden technological shift in listening: by 1992, CDs had quickly become the predominant recorded music format in the US. Here in Cambridge MA, both Tower Records and HMV opened branches in the fall of 1991 with massive, gleaming expanses of CDs. Naturally there were posters in the windows and prominent displays for the latest chart hits, including Nirvana’s Nevermind. But there were also huge areas of these stores devoted to classical, jazz and “world” music – the depth in these genres was entirely different from what we had access to before. I went on a listening spree, and was far from alone; CDs fueled a steep expansion of the recorded music industry, peaking in 1999 at a point it has yet to reach again.

The story of that boom is usually told in terms of popular music, and the novelty of platinum-selling releases in country, hip-hop and my own genre which for some reason became known as “alternative.” But that doesn’t explain all the square footage in Tower and HMV devoted to classical, jazz and world. Without topping the charts, these genres were selling like never before, too. And surely that was due to their being available like never before.

Does that make these genres very 1991?

They were certainly well suited to the newly ascendant format. CDs were designed to hold 74 minutes and 33 seconds of uninterrupted music – nearly but not quite double the length of an LP (which starts to max out at roughly 22 minutes a side). Famously, this new 74:33 standard was said to have been calculated to contain Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony at even its most ponderous tempo (Furtwängler’s 1951 performance at Bayreuth comes in just under the line), because it was Sony director Norio Ohga’s wife’s favorite piece. Dutch engineer Kees Immink, who worked on the development of the CD for Philips, Sony’s partner in the project, has written that behind that anecdote lies a lot of corporate wrangling connected to competing patents and manufacturing plants… Be that as it may, the CD was always destined to favor longer programs.

The CD’s capacity opened up all kinds of recording possibilities – but not particularly for album-oriented rock, which didn’t really know what to do with the additional half-hour. It wasn’t quite enough for a double-LP (which ended up as expensive two-CD sets with an awkwardly short run time). And it was much more than bands and listeners were used to from a single LP; “bloated” became a familiar reviewer’s term, until everyone learned to market filler as “bonus tracks.”

Classical music was of course well suited to the longer format – neatly enough for Sony’s suspect anecdote about Beethoven’s Ninth to pass into accepted lore. Jazz readily adapted – perhaps it’s no coincidence that Rahsaan Roland Kirk’s anomalous “The Case of the 3 Sided Dream in Audio Color” (1975) made what must have been the neatest transfer to CD of any existing LP set (total run time for its three vinyl sides = 73:44). And there was an explosion of recordings of live and improvised musics from all over the world – precisely what is documented by On the Edge - which had always been something of a mismatch with the temporal confines of vinyl.

If I think of my 1991, I might reach for this “JVC World Sounds” CD from 1990 by Qawwali singer Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan – its white jewel case still gives me a frisson of 80s Japanese modernity:

“JVC World Sounds is a series of CDs featuring the traditional music unique to many countries, music which people all over the world enjoy listening to and performing,” declares a note inside the booklet. “The most advanced recording techniques have been used in order to present the music in all its natural freshness. This collection featuring musical voices from every corner of the globe is now being offered by Japan to the world.”

Oh, the confidence and optimism of boomtime Japan! Its global ambitions, its fetishism of technology, its idiosyncratic use of English, its white jewel cases and silver discs… There is a world view at work here, as well as an economic system of globalization that placed this digital recording of a living ancient tradition in my local Tower Records for me to see, want, and start listening to obsessively in 1991.

Again, I was far from alone. Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s devotional Sufi music became something of a sensation in the US of the 1990s – Kramer, our manic, cynical, stoned, downtown New York producer, went to see Nusrat and his group perform at Town Hall and, as he told me and Naomi during our sessions for More Sad Hits, wept uncontrollably through the entire show. By 1996, Nusrat was selling out Radio City Music Hall, and Neil Strauss was gushing in the New York Times:

“He is one of the world's biggest stars… He has been interviewed on MTV and VH1 and collaborated with Eddie Vedder of Pearl Jam and Peter Gabriel. Joan Osborne went to Pakistan to ask for singing tips, and in Los Angeles last week, Madonna and Michael Stipe of R.E.M., in addition to the actors Stephen Dorff and Rosanna Arquette, showed up at a concert…”

Even Rick Rubin came knocking. (The resulting recordings, made shortly before Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s death in 1997, are not widely recommended by fans.)

I doubt many people think of the sound of the nineties as Qawwali. But it was very present, together with a world of live and improvised music newly captured for reproduction on CD. I do feel that 1991 was an inflection point in the music industry. But given how we are more dependent than ever on live performance… might it be this aspect of 90s recordings - its emphasis on longer, more spontaneous formats - that ultimately determined even more for music today, than grunge?

Listening to: Richard Youngs, CXXI

Cooking: Membrillo (quince jam)