Now we’re in the thick of it, I’ve found myself reaching for work made in the early 1940s… Thinking under fascism feels like hearing under water, it’s a different medium and everything seems distorted if you don’t account for it.

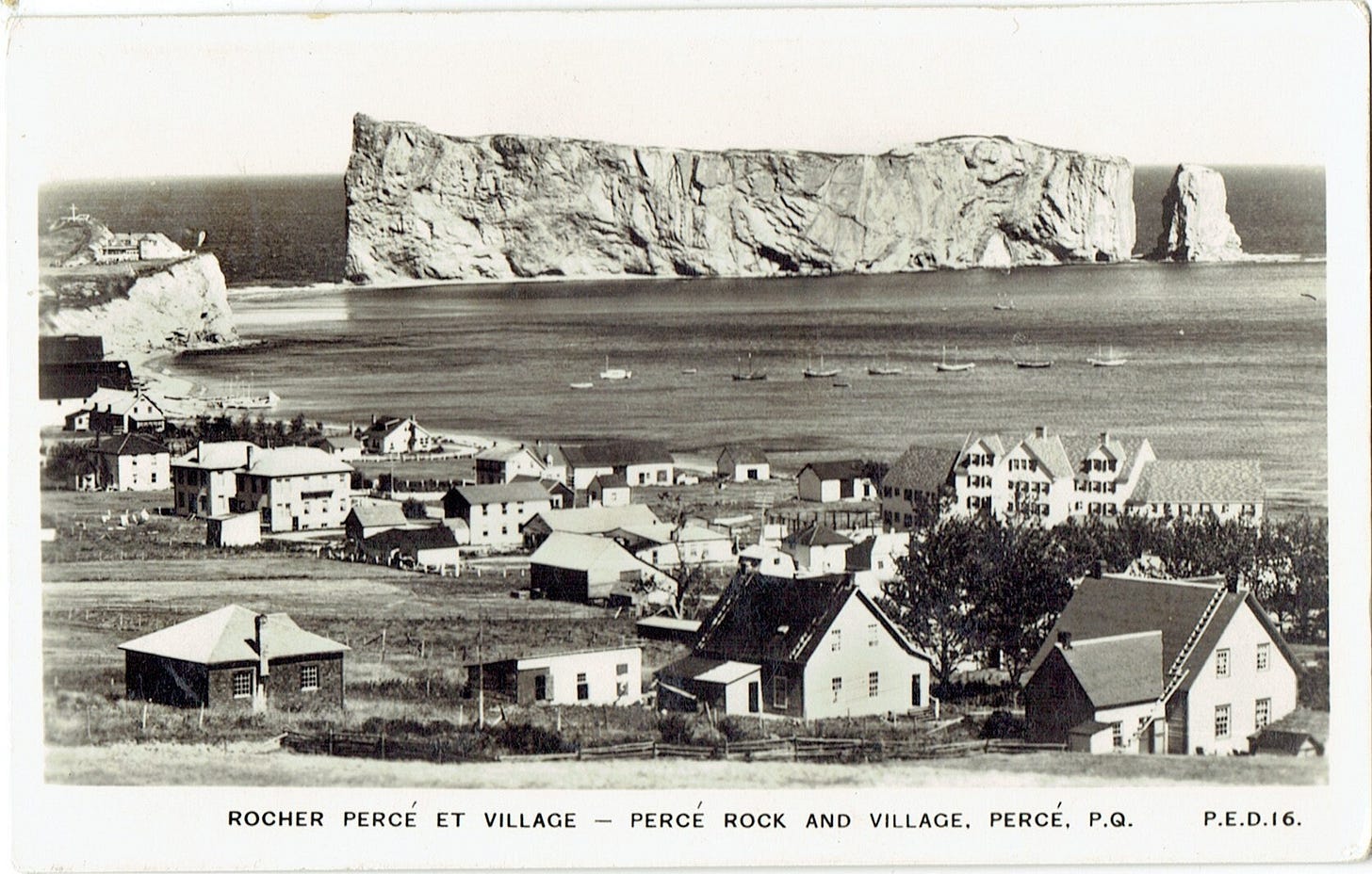

I am rereading André Breton’s Arcanum 17, written from exile in Quebec during the Nazi occupation of France. Breton, the great surrealist and champion of the fantastic, the irrational, the dream, found himself in 1944 literally staring at a rock: Percé Rock, off the Gaspé Peninsula in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. The end of the earth, in French terms.

Breton’s meditation on this isolated rock in an isolated place seems an effort to hold on to reality in the midst of societal madness. But Breton’s reality had always been a path into the unreal, and he works to hold on to that too.

“A detour through the essential, such as one experiences each time there’s a threat to one’s individual existence or even to the pursuit of one’s personal destiny within the framework of that existence. I maintain that when the nature of events tends to head them in a direction that is too painful, people’s feelings find, despite themselves, a refuge and a springboard in the most perfect expressions of what is not real, I mean those where a completely different ‘reality’ has been able to make the eternal, until reabsorbed in the distance, spring forth.”

What I see in Arcanum 17 — an uncharacteristically prosaic book in some ways — is the value in upsidedown times of not only fact (a rock), but one’s own version of fact, which for Breton remained “what is not real.” A paradox for a surrealist in fascist times, yes. But emblematic of the situation any of us working in art might be in now, if we feel the need to ground ourselves in order to continue leaving the ground behind.

I also rewatched Charlie Chaplin’s The Great Dictator (1940), his remarkable response to having been twinned by a mustache with, of all people, Hitler. (They were also exactly the same age, born four days apart.) Casting himself as both the fascist dictator (“Adenoid Hynkel”) and a Jewish barber (nameless, like all his versions of “the Tramp”), Chaplin constructs a tragicomedy from mistaken identity between the two. To appreciate the drama of the final scene, in which Chaplin speaks straight to camera, it’s useful to know that when sound arrived for movies in 1927 Chaplin refused to alter his techniques. Throughout the 1930s, he continued – the only one in Hollywood - to make silent or near-silent feature films. Even in The Great Dictator, which was Chaplin’s first proper “talkie,” his characters (both of them) refrain from intelligible speech as much as possible. Until the final scene, where the Jewish barber, dressed as the fascist dictator, addresses the fictional and historical audience directly:

“Greed has poisoned men’s souls, has barricaded the world with hate, has goose-stepped us into misery and bloodshed. We have developed speed, but we have shut ourselves in. Machinery that gives abundance has left us in want. Our knowledge has made us cynical. Our cleverness, hard and unkind. We think too much and feel too little. More than machinery we need humanity. More than cleverness we need kindness and gentleness. Without these qualities, life will be violent and all will be lost…

“To those who can hear me, I say - do not despair. The misery that is now upon us is but the passing of greed — the bitterness of men who fear the way of human progress. The hate of men will pass, and dictators die, and the power they took from the people will return to the people…

“Soldiers! don’t give yourselves to brutes - men who despise you - enslave you - who regiment your lives - tell you what to do - what to think and what to feel! Who drill you - diet you - treat you like cattle, use you as cannon fodder. Don’t give yourselves to these unnatural men - machine men with machine minds and machine hearts! You are not machines!…

“Dictators free themselves but they enslave the people! Now let us fight to fulfill that promise! Let us fight to free the world - to do away with national barriers - to do away with greed, with hate and intolerance. Let us fight for a world of reason, a world where science and progress will lead to all men’s happiness. Soldiers! in the name of democracy, let us all unite!”

This wildly uncharacteristic action for Chaplin’s silent character the Tramp was taken at the time – and still is – as an impassioned anti-fascist speech from Chaplin the artist. FDR invited him to recreate it on the radio during his third inauguration in 1941. And J. Edgar Hoover, the supremely evil lifetime head of the FBI from its foundation in 1935 until his death in 1972, was moved by it to label Chaplin an enemy of the state. The FBI proceeded to hound Chaplin throughout the 1940s, covertly (his phones were tapped, his mail opened, damaging stories fed to the press), and overtly through collaborating Republicans in Congress. Senator Langer of North Dakota introduced a bill calling for Chaplin’s deportation in 1945, and a few years later the House Un-American Activities Committee denounced him as a communist sympathizer. Ultimately, Chaplin was forced into exile not only from Hollywood but from the US altogether in 1952, when his visa was revoked while en route to the UK.

The fallout from Chaplin’s anti-fascist speech in 1940 is a sharp reminder that the other side has always been active here – even in the midst of an international war against fascism. Chaplin himself wrote, in rejoinder to Sen. Langer in 1945:

“I wish to state that this action is part of a political persecution. It has been going on for… years, ever since I made an anti-Nazi picture, The Great Dictator, in which I expressed liberal ideas. On account of this picture I was called to Washington for questioning as a ‘War monger’ by Senators Clark and Nye. This investigation fell through after Pearl Harbor. The persecution, however, increased, after I ‘dared’ to speak on behalf of Russia, urging the Allies to open a second front. For this I was bitterly attacked by reactionary columnists, using every device to discredit me with the public. I was called a ‘Communist,’ an ‘ingrate’… I believe that in a democracy I have the right to state that I am an Internationalist — which ideas I expressed in The Great Dictator. But the pro-Nazi reactionary elements continued their attack.”

Silencing opposition is part of the fascist program, quite obviously. But so is upending communications that they otherwise can’t prevent – changing the meanings of words, distorting the record of fact, denying the power of image beyond kitsch. This is the environment we find ourselves in, but it is hardly new. I take some comfort and what courage I can by looking to artists from the past who were forced to struggle against these same reactionary forces.

We must also look to each other – and after one another - here in the present.

Listening to: Salt River, by Sam Amidon

Cooking: Eggs, when I can get them

Wonderful post. Cling to what is true and good. We Europeans remain with you.

Wow. This was fucking brilliant and an eye opening read. Thank you for providing the context and fallout around Charlie Chaplin and “The Great Dictator.” I had only ever seen the speech clip used as some inspirational meme. Telling of this moment’s obsession with fast/partial/truncated blurbs.